• The ‘vixen was sniffling and coughing yesterday, probably from allergies, but she called out sick because that’s always been the rule at the salon. Nobody wants to get their hair cut by someone who might be contagious.

Since the start of this pandemic, there’s another rule as well: Anyone with symptoms — even those probably just from allergies — has to stay out of work until after they get a negative COVID test. This is a good rule, but it was an even better rule last year, when the salon was still offering unlimited sick time and/or the possibility of filing for a meaningful unemployment check until you were symptom-free and certified negative.

The salon, like the Big Box where I work, had all kinds of important, necessary pandemic policies like that in place last year. But the salon, like the Big Box and thousands of other businesses, just kind of stopped all of that, gradually, once the vaccines became available. I guess they were assuming — understandably, if mistakenly — that the availability of free vaccines would mean everyone would get them and we’d be able to start getting back to normal.

Anyway, in a healthy, functioning country that wasn’t hobbled by the checks and balances of a White People’s Party-turned-death cult, my wife could have just taken one of the COVID self-tests that came in the mail with our weekly supply of masks, public health-updates, etc. Alas, no such weekly mailings are sent or received in our country because, again, WPP-turned-death cult. So I had to go to CVS to kick out $23 for the test kit.

The result, thankfully, was negative. This blessed news would have felt more like cause for celebration if it weren’t shadowed by the realization that many, many of our neighbors can’t easily afford to take more sick time and/or to shell out $23 to confirm that they’re not carrying a potentially deadly virus.

• Agnes Howard writes at the Anxious Bench about “Piety and Public Health in Early America.” Howard focuses on Lutheran minister Heinrich Helmuth who stepped up during the yellow fever epidemic that swept through Philadelphia in 1793 — when Philly was still the nation’s capitol. About a tenth of the city died in that epidemic, while nearly half the population fled to the surrounding countryside.

Howard also links to a Smithsonian article by Alicia Ault on “How the Politics of Race Played Out During the 1793 Yellow Fever Epidemic.” What happened was that Benjamin Rush — a medical doctor as well as a bona fide “Founding Father” — mistakenly thought that Black people were immune to yellow fever. So Absalom Jones and Richard Allen offered the services of their new church and their Free African Society to minister to the sick, serving as nurses, tending to the dying, and burying the dead.

The Black church volunteers soon realized that Dr. Rush was wrong about their supposed immunity to the plague. But they also realized that very few of their white neighbors were sticking around to aid the sick and the dying, Black and white alike, so they kept going, risking their own lives to aid and comfort others. For their enormous contribution in saving the nation’s capitol, the Black volunteers were publicly criticized and accused of plundering the dead.

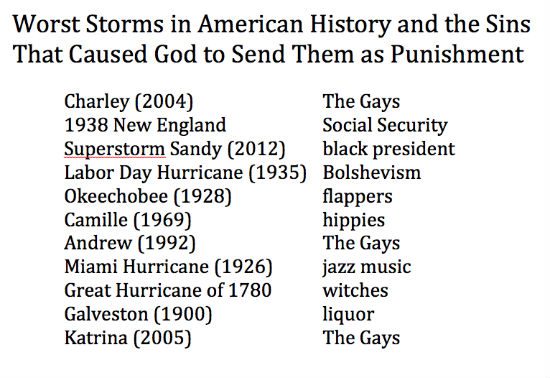

Neither Howard nor Ault gets into another religious response to the epidemic of 1793, which was a pious campaign to outlaw theater in Pennsylvania as, in the minds of some clergy, the pestilence was surely God’s judgment on the lax morality of allowing such a thing to exist in the commonwealth. I’d update the chart below to include that, but epidemics don’t really fall under the category of sanctimonious meteorology, which is maybe why the usual suspects have been mostly mum in blaming the current pandemic on their usual scapegoats.

One more productive result of the yellow fever epidemic of 1793 was the construction of the Philadelphia Lazaretto (above), which I wrote about a few years back after attending a wedding there:

The Philadelphia Lazaretto [was] founded in 1799 as a quarantine hospital for travelers and immigrants arriving in what was then the nation’s capital. It replaced the previous facility — the Old Lazaretto or “pest house” in the city — after a yellow fever epidemic in the 1790s claimed the lives of about a tenth of Philadelphia’s population. The Lazaretto operated for more than a century, and some guess that as many as a third of all Americans “have an ancestor whose first contact with the New World was at the Lazaretto.”

This seems to me to be an instance where we can and should learn more from the example of America’s “founding fathers” — even if it’s not the sort of thing that the folks who fetishize the founders like to talk about. Contrast the prudence and practicality of establishing this facility with the ugly, irrational panic we saw recently in response to the recent Ebola outbreak in West Africa. The Adams administration didn’t freak out, lose its head, and overreact with talk of closing all the ports and barring all immigration, travel and commerce. Instead, they built a humane facility and set up a new process using the best medical information available at the time.

The term “Lazaretto” for quarantine hospitals, by the way, takes its name from older Christian leper colonies, and thus ultimately from the parable of Lazarus and the rich man in the Gospel of Luke. (That’s one of my favorite Bible stories, partly because it unambiguously presents a soteriology that most defenders of orthodoxy would proclaim to be “unbiblical.”) That captures something of the ethos of such facilities. The sick must be cared for, first of all, because they are sick. Period. But it is also in our self-interest to care for them, because if we fail to do so, there may be Hell to pay.