“What Is ‘Progressive Christianity’?” Roger Olson asks. This is in a post on Patheos’ Evangelical Channel. If you’re at all familiar with the origins of Patheos, or with it’s more recent involvement in boosting and shaping the term “progressive Christianity,” then you’ll understand why that’s hilarious.

I offered an initial brief-ish response to Olson’s question in this Twitter thread. The short version is that “progressive Christian” isn’t a theological category, but a political one. It’s a squishy term because it has come to be used to refer to just about every Christian who doesn’t fit in with the polarized partisan identity and politicized culture of white evangelicalism. “Progressive Christianity,” in other words, is a political category because it’s used in contrast with white evangelicalism, and white evangelicalism is a political category, not a theological one.

Patheos adopted the label “Progressive Christian,” replacing the former “Mainline Protestant,” when it moved several blogs — including this one — off of the Evangelical Channel that hosts Roger Olson’s blog. They had to change that name because we were not “Mainline Protestants,” we were evangelicals. But having our voices there on the Evangelical Channel was perceived as off-putting to would-be evangelical readers who would be horrified by our non-Republican politics and our not-Hannity-friendly culture.

So “What Is Progressive Christianity?” according to the website that hosts Roger Olson’s blog? It’s not liberal theology, although it may include that. It’s simply any form of Protestant Christianity that does not expect and require the Republican politics expected and required within white evangelicalism. “Everything else” turns out to be a less-than-precise category, which is why the term “progressive Christian” gets applied not just to “Tree huggin’, love makin’, pro choicin’, gay weddin’, Widespread Panic diggin’ hippies like me” but also to people like Russell Moore and Beth Moore.

George Marsden, contending with the difficulty of defining a perpetually contended category like “evangelical,” once joked that an evangelical is anyone who likes Billy Graham. In the current usage, popularized by the website you’re reading right now, “progressive Christian” refers to anyone who does not like Franklin Graham.

The original idea of Patheos — back before it started adding blogs and columnists and such — was to be an online resource to help people understand and navigate religious pluralism. Say your new coworker is Buddhist, or your new neighbor is Lutheran, and you don’t know what that means. Patheos’ goal was to be a one-stop site where you could be introduced to the beliefs, practices, and customs of these new friends, with the descriptions of each tradition written by people from that tradition.

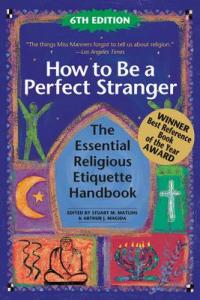

The idea was something like the book How to Be a Perfect Stranger, which is a terrific resource for explaining and demystifying the religious beliefs of your neighbors in a pluralistic society. Perfect Stranger is a kind of etiquette guide for the unfamiliar situations we can all face due to our robust variety of religions. What should you do if you’re invited to a wedding or a funeral in an unfamiliar tradition? What’s the appropriate holiday greeting for your coworkers’ religious occasions?

The idea was something like the book How to Be a Perfect Stranger, which is a terrific resource for explaining and demystifying the religious beliefs of your neighbors in a pluralistic society. Perfect Stranger is a kind of etiquette guide for the unfamiliar situations we can all face due to our robust variety of religions. What should you do if you’re invited to a wedding or a funeral in an unfamiliar tradition? What’s the appropriate holiday greeting for your coworkers’ religious occasions?

Both the original version of Patheos and How to Be a Perfect Stranger were lovely expressions of Krister Stendahl’s advice to cultivate “holy envy” — to seek out and to honor that which is admirable in our neighbors. Stendahl, the late Lutheran bishop of Stockholm, presented that advice in 1985 in response to the outcry over the proposed construction of an LDS temple in Sweden. He laid out three “Rules of Religious Understanding”: 1) When trying to understand a religious tradition, talk to people from that tradition, not to their enemies; 2) Don’t compare their worst to your best; and 3) “Leave room for holy envy.”

Stendahl’s rules, like Perfect Stranger and ca. 2002 Patheos, were based on — and contingent upon — two vital assumptions: A) You are not an asshole; and B) You do not want to be an asshole, even inadvertently. These are necessary premises for neighborliness, interfaith justice, legal equality, and religious liberty — which is why all of those things tend to be in short supply.

Stendahl regarded his three rules as an expression of the imperative to “love thy neighbor.” They were meant to help us to love our neighbors, and to be good neighbors, in a world shaped by religious pluralism.

But it’s not so simple for those of us from conversionist religious traditions. Sure, it’s nice to be polite and hospitable, and even to allow a modicum of legal religious liberty for false religions, but there’s nothing nice or polite about allowing those neighbors to burn in Hell for eternity. If we really love them, then we’ll need to confront them with the need to convert and to be saved and spared from eternal punishment. And if they interpret such confrontational concern for their eternal fate as rude or impolite, well, that’s a small price to pay when the stakes are so infinitely high.

When I first encountered How to Be a Perfect Stranger, I was struck by the familiarity of its structure. It reminded me of several books I had read growing up in a white fundamentalist church and private school. Those also presented themselves as guidebooks to religious pluralism, but their intended purpose was very different. Some of those books were written as evangelistic how-to guides: How to evangelize to Jews; how to witness to Catholics; how to present the gospel to Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Hare Krishnas, Episcopalians, atheists, Muslims, and Buddhists.

And those were the better books. The others presented themselves as “apologetics,” violating Stendahl’s first rule by describing the vast array of world religions in the terms of outsiders and of their enemies and critics. Some of these “apologetics” guidebooks seemed intended to prepare their Christian readers for debate with anyone they encountered from these other traditions. More often, though, the purpose of these “apologetic” guides to religious pluralism seemed to be inoculation. Here is a bestiary of false religions you must shun and condemn. Beware of your neighbors, they will lead you astray.

The authors of those books couldn’t hear what Stendahl was saying or understand what the founders of Patheos and the editors of Perfect Stranger were trying to do. For those authors, the goal of loving our non-Christian (i.e., non-the-right-kind-of-Christian) neighbors seemed indistinct from saying “Live and let live, it’s all the same, nothing is true and nothing is truer than anything else.” To them, interfaith neighborliness — or even simply ecumenical Christianity — was misguided at best and, at worst, an assault on “absolute truth” itself.

The problem is that any alternative to the kind of neighbor-love expressed in Stendahl’s three rules is bound to end up with the hateful suspicion, shunning, and condemnation of those “apologetics”-themed guides to world religion. The neighbor-love of those other evangelical guidebooks — the ones driven by a fiercely urgent need to convert those neighbors in order to spare them from Hell — turns out to be unsustainable. The genuine love of neighbor that compels this white-knuckle evangelism will eventually lead in one of two directions. It will either curdle into resentment and condemnation of the unsaved, or else it will blossom into grace.

Someone who is genuinely driven to evangelize based on a genuine love of neighbor is eventually going to recognize what that means. It means “I love my neighbor, and if one loves another person, then one is compelled to do everything in one’s power to ensure that they do not suffer torment for all of eternity.” And thus either I am claiming that I am capable of loving my neighbor more than God loves them, or else I am guilty of loving my neighbor more than God thinks I should. If I conclude the latter, then I must repent of this love for neighbor and align myself with God’s delight in the prospect of their eternal torment. But if I conclude the former, then I must come to realize that God’s love and mercy must vastly exceed my own, and therefore some of my assumptions about grace and torment and soteriology are in dire need of revision.

That requires some unlearning — or “deconstruction,” as the kids say these days — but it has nothing to do with reading Schliermacher and Bultmann or whatever it is that Olson worries those “progressive Christians” are secretly on about.

This suggests that we might have some theological grounds for distinguishing between the mostly political categories of “evangelical” and “progressive Christian.” A “progressive Christian” is someone that evangelicals believe is outloving God. “Progressive Christianity” holds that it’s impossible to do that.