I mentioned in the previous post that Abraham Clark is a part of my own family tree. I am not a direct descendant of that signatory of the Declaration of Independence, but of his first cousin, Matthias Clark, who was a captain in the New Jersey militia and fought at Saratoga during the Revolution.

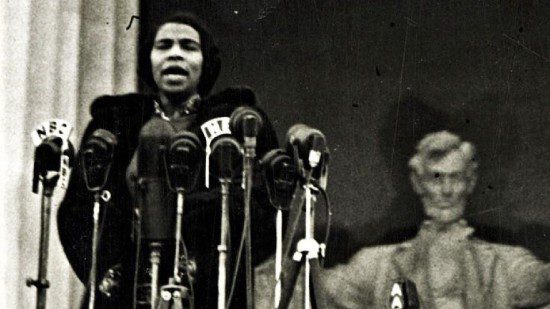

Thanks to old Matthias, my sister was “qualified” to join the Daughters of the American Revolution. This happily provided her with the opportunity to send them a letter politely explaining why she’d never want to be a part of that infamous gang of pseudo-eugenic snobs.

Both Abraham and Matthias were great-grandsons of Richard Clark(e), who arrived on Long Island as a whaler in 1640 before settling in what is now Union County, New Jersey. My dad thoroughly documented that line of Jersey Clarks (Richard’s son dropped the ‘e’) from 1640 all the way down to, well, me. I was born right there in Union County. We Clarks, apparently, missed the memo on that whole “Go West” business, although I did finally cross the Delaware in 1986 and now live on the western frontier in Chester County, Pennsylvania.

Dad caught the genealogy bug after receiving a letter from Florence and Gladys Whitehead, distant cousins who wrote to inform him that he was, according to their own genealogical research, their closest living relative. After exchanging a few more letters, our whole family wound up putting on our Sunday best and driving to Rahway to meet the cousins. They were amazing. Florence and Gladys were spinsters (their term) — unmarried sisters in their 70s, both just barely 5-feet tall, who were still living in what had been their parents home not far from the penitentiary and the cemetery.

Their house was a museum. Old photographs and honest-t0-God daguerrotypes hung on the walls — all at what was, to them, eye level. When I first saw their television, I didn’t know what it was. It looked to me like some kind of wood-finish jukebox, with unlabeled dials and a tiny, almost round screen. It still worked and they would warm it up every evening, twisting those dials to watch Al Roker and Sue Simmons on Live at Five in black and white. The thing still ran even though its tubes and other parts hadn’t been made since Philo Farnsworth had died. They had somehow become friends with an eccentric tinkerer who lived in Brooklyn and took the train out every month or so to have some tea and keep their ancient set in working order. He didn’t charge them — he just wanted the privilege of getting to handle such a thing.

My brother and I went to the Whiteheads house once to get an antique foot-pump table saw down from their attic for them because “a man was coming to pick it up” a few days later. The man turned out to be from the Smithsonian. The national collection already had a saw like that but, unlike the one we carried down from the attic, it didn’t still work.

Back on that first family visit, Florence and Gladys took us all to the cemetery in Rahway to see where all of the Whiteheads were buried, right near three centuries of Clarks, including Abraham himself and Matthias and the rest of their generation. And just like that, Dad was hooked. Genealogy became his hobby and his passion for the rest of his life, not from any sense of pedigree or the weird genetic pride of groups like the DAR, but from the sense of history and connection and the satisfaction of seeking and finding all of the pieces of a puzzle. And I think he loved finding and becoming a part of a larger community of others seeking to put their family puzzles together too.

I got a very nice letter just a few months ago from a man in Missouri expressing his condolences on my father’s death and asking if we might still have any of the information Dad had put together about his family tree — a family not in any way connected to Richard Clark(e) or any of his offspring. (We’re trying to find that for him — Dad’s papers are a mess and a lot of this stuff is still on floppy disks using now-defunct genealogy software.)

I had a girlfriend in college whose last name was also Clark. It’s a common surname, after all, and my father liked to say that I was more likely to be related to someone named “Smith” than to someone also named Clark. But Dad did half-jokingly double-check for us and confirmed we weren’t related in any way — at least as far back as 1640.

I am, however, a distant relative (1oth cousins or some such) of the Bushes. And the Cheneys. And of the Dunhams and, therefore, also of the Obamas. That wasn’t through old Richard, but through the Throops/Stroops and the Lathrops/Lowthorpes and through the myriad of other large, old families that pretty much anyone who’s been here long enough is linked back to in one way or another. If your family has been around since Jonathan Edwards’ time, then in one way or another you’re gonna be related to Edwards and to all the signers of the Declaration and to almost every president (excepting the most recent two).

Warinaco Park is about 10 minutes away from that cemetery in Rahway. That’s where we played the first three seasons of Bread of Life baseball. That team had two pitchers and two shortstops, me and Ernie Clark. If I was pitching, Ernie played at short, and vice versa (he was better at both positions than I was). Because we had the same last name, we joked that we were brothers. This was hilarious to us as little kids because I’m white and Ernie’s Black.

I’d long since lost track of my childhood friend and teammate by the time my father got really interested in — and really good at — genealogical research. But years later Dad and I both wondered a bit at our old joke. All Ernie knew about his family history back then was that his grandmother was from Plainfield, just as her parents had been, and their parents too, she thought. So these Clarks had also been settled there in Union County for a long time, maybe even since back in the days of slavery.

We tend to gloss this over in history classes where slavery is mostly discussed only in the context of the Civil War, creating the false impression that it was exclusively a Southern thing. Even when slavery gets taught in other contexts — like in the debates over the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution — we speak in terms of Northern states and Southern “slave” states. But in 1776, and in 1789, that geographical distinction wasn’t so simple. Slavery was legal throughout the entire colonial period in New Jersey, and it was still legal there during the constitutional convention after independence. The state didn’t formally outlaw slavery until 1804, but it was a gradual emancipation with plenty of loopholes, and applying only to those born after the law passed. The final 16 slaves in the Garden State were not freed until 1865, after the ratification of the 13th Amendment.

Richard Clarke “owned” slaves in Union County, New Jersey, and Richard Clark inherited them in his father’s will. Abraham Clark was a slaveowner. My dad never found anything to prove that Matthias Clark enslaved people, but he also never found anything to prove he didn’t, so he probably did. What happened to those families enslaved by my family after 1804? What became of their children? What surnames did they choose or adopt or have assigned to them?

My dad never found any answers to those questions in all of his genealogical research. Nothing he came across in his years of photographing cemeteries and digging through old family Bibles and historical society archives included anything about those families that had been, for generations, bound to ours by violence and literal chains.

So we don’t know. But it’s possible that Ernie and I really were related. Possibly by “blood,” or possibly by that crueler form of all-American kinship. Possibly by both.

Probably not, of course. It is, again, a very common surname, and I’m more likely to be related to someone named “Smith,” etc. But then again Union County isn’t that big. So.

What does it matter? What would it mean? Maybe nothing. Maybe everything.

Maybe someday I’ll come across my old childhood teammate again. I’d love to just have a catch and get a chance to ask him about his family. Or maybe about our family. And if it turns out he’s got any daughters, maybe we’ll talk about whether or not they should join the DAR.