“I know an old lady who swallowed a fly,” the old song begins. Swallowing a fly is unpleasant and not at all something to be recommended. It’s gross, but it probably won’t kill you — which is why the song is joking when it says, “Perhaps she’ll die.”

That’s the point of the song — that the old lady would certainly have survived swallowing the fly if not for the increasingly drastic measures she took thereafter. She swallows a spider to catch the fly, then swallows a bird to catch the spider, then swallows a cat to catch the bird, etc. Until finally, “I know an old lady who swallowed a horse. She’s dead? Of course.” And the song ends, because swallowing a horse is much more serious than swallowing a fly.

That’s an old song but it borrows, perhaps, from an even older bit — one of Jesus’ funnier rants in the Gospel of Matthew:

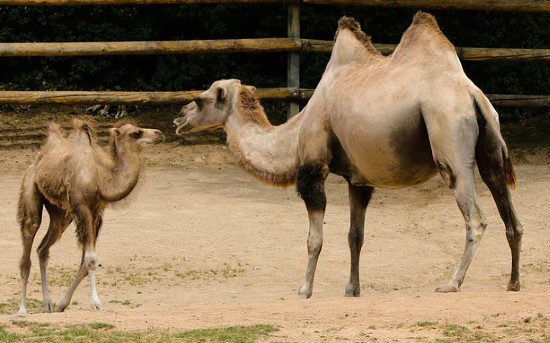

Woe to you, pastors and theologians, hypocrites! For you tithe mint, dill, and cumin, and have neglected the weightier matters of the law: justice and mercy and faith. It is these you ought to have practiced without neglecting the others. You blind guides! You strain out a gnat but swallow a camel!

Jesus isn’t quite as harsh as Isaiah or Amos. He doesn’t wholly dismiss the pious virtues these religious leaders were practicing in lieu of justice and other, “weightier matters.” Where Isaiah and Amos depict God as despising prayer, worship, sacrifices and tithes, Jesus allows that they may have some value too — albeit a lesser, slighter, importance.

Highlighting Jesus’ severe contrast tends to rankle many of my white evangelical friends. A sin is a sin is a sin, they insist, and every sin — no matter how apparently insignificant — separates us from God and makes us deserving of eternal damnation. Don’t mock those pious religious leaders for tithing their spice racks — get on your knees and beg for God’s forgiveness for your own failure to do the same. Look — there’s Jesus himself commanding us not to neglect such commandments!

But treating this passage as a confirmation of the equivalence of every sin is, well, a desperately strained reading. Jesus’ point here is that there are “weightier matters,” and he illustrates the vast difference in significance by contrasting something proverbially tiny with something proverbially huge. (Nobody in first-century Palestine knew what an elephant was, so the “elephant in the room,” for them, was a camel.)

And Jesus isn’t really that far off from Isaiah and Amos. Those prophets were more sweeping in their dismissal and condemnation of all forms of religion apart from “the weightier matters,” but they also allow that such things might be of some worth if they were done in addition to the pursuit of justice. Their message is akin to what Paul writes in that passage we read at weddings — that without love and justice, even worthy-seeming things are worthless, nothing more than clanging gongs and tinkling cymbals.

See Isaiah 1, for example. Or this bit from Amos 5:

I hate, I despise your festivals,

and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies.

Even though you offer me your burnt offerings and grain offerings,

I will not accept them;

and the offerings of well-being of your fatted animals

I will not look upon.

Take away from me the noise of your songs;

I will not listen to the melody of your harps.

But let justice roll down like waters,

and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.

The people have neglected justice and, without that, anything else they do is worthless and hateful to God. That’s the point of the entire chapter and, indeed, of the entire book of Amos, which offers an angry litany of injustices. Here’s more just from chapter 5:

Ah, you that turn justice to wormwood, and bring righteousness to the ground! … They hate the one who reproves in the gate, and they abhor the one who speaks the truth … you trample on the poor … For I know how many are your transgressions, and how great are your sins — you who afflict the just, who take a bribe, and push aside the needy in the gate.

And here’s Amos (or God, according to Amos), railing against injustice in chapter 8:

You that trample on the needy,

and bring to ruin the poor of the land,

saying, “When will the new moon be over

so that we may sell grain;

and the sabbath,

so that we may offer wheat for sale?

We will make the ephah small and the shekel great,

and practice deceit with false balances,

buying the poor for silver

and the needy for a pair of sandals,

and selling the sweepings of the wheat.”

In chapter 4, Amos/God declares deadly judgment on “You cows of Bashan who are on Mount Samaria, who oppress the poor, who crush the needy, who say to their husbands, ‘Bring something to drink!'” And here’s another pre-Jeremiah jeremiad against injustice from Amos chapter 2, verses 6-8:

Thus says the Lord:

For three transgressions of Israel,

and for four, I will not revoke the punishment;

because they sell the righteous for silver,

and the needy for a pair of sandals—

they who trample the head of the poor into the dust of the earth,

and push the afflicted out of the way;

father and son go in to the same girl,

so that my holy name is profaned;

they lay themselves down beside every altar

on garments taken in pledge;

and in the house of their God they drink

wine bought with fines they imposed.

The people have swallowed injustice, swallowed a camel, swallowed a horse. They’re doomed? Of course.

If you’ve been trained to expect the Bible to be mostly about idolatry and adultery, then you may have to read the book of Amos several times before you’re able to recognize that those sins are almost entirely absent here. It’s all about injustice, oppression, and the exploitation of the poor. Every mention of something that sounds maybe a bit like idolatry (“they lay themselves down beside every altar …”) is condemned for being in the service of injustice (“… on garments taken in pledge”).

So it was a bit hard to swallow when prominent white evangelical pastor Tim Keller attempted to cite this same book of Amos as somehow proving that gnats and camels are of equal concern.

Keller warns against “modern political ideologies” that “pressure Christians to separate social injustice and sexual immorality and emphasize one over the other.” This modern ideology, Keller says, is something the Bible does not do, citing chapter and verse to demonstrate his point.

Alas, the chapter and verse he cites doesn’t support the point he thinks needs to be made here. It massively undermines it.

Here’s Keller’s tweet:

See Amos 2:7 where God condemns social injustice and sexual immorality in the same breath, as being of a piece. Modern political ideologies pressure Christians to separate them and emphasize one over the other. The Bible does not do that.

The Bible does do that. It doesn’t “separate them,” that’s true, but in the precise passage that Keller cites the Bible very much does “emphasize one over the other.” Amos says God is angry with a whole host of economic sins — forms of “social injustice” that exploit the poor and the vulnerable. And mixed in with all of that is one mention of one thing that might also perhaps be placed into a column labeled “sexual immorality.”

If Amos/God had intended to emphasize the equivalent importance of both of these things, then Amos/God is doing a lousy job of that here in Amos 2:6-8. And in the rest of Amos 2. And in the rest of the book of Amos.

And also, frankly, in the rest of the Bible, where the ratio of condemnations of “social injustice” versus condemnations of “sexual immorality” is about the same as it is here in these three verses. The Bible does that. The Bible has a lot more to say about the things that Keller would lump into the category of “social injustice” than it has to say about the things he would classify as “sexual immorality.”

That does not, in itself, mean that Keller is wrong to suggest that these two categories are of equivalent importance. The relative importance or significance of various sins cannot simply be tallied up by counting verses. But Keller seems to think counting verses would support his contention, when it very much would not.

It’s also interesting that condemnations of “sexual immorality” are particularly rare in the also-rare biblical passages primarily addressed to the poor. (Much more of the Bible is, like Amos 2, addressed to those oppressing and/or neglecting the poor, rather than being addressed to the poor themselves. Dives gets lectured. Lazarus doesn’t.) If “social injustice” and “sexual immorality” were, indeed, biblical themes of equal weight and urgency, then one would expect that passages primarily addressed to the poor would be preoccupied with condemnations of their sexual sins. It’s not surprising that the poor are not lectured about the sins of social injustice because, after all, they’re on the receiving end of those sins and aren’t the ones who need to hear those lectures. But if the sexual immorality that tempts us all is equivalent to justice and the “weightier matters,” then wouldn’t the poor still need to hear a lecture warning against it?

Yet the prophets do not provide such lectures for that audience. The “sexual immorality” of the oppressors sometimes draws their wrath, but the sexual ethics of the poor seem not to concern them at all.

Again, none of that proves that Keller is wrong to argue that “social injustice” and “sexual immorality” ought to be viewed as matters of equivalent importance. But it is clearly very wrong to suggest, as Keller does, that Amos 2 or “the Bible” as a whole addresses these subjects an equivalent amount or in an equivalent manner.

The biggest problem here, though, is something subtler. Keller has created a category he labels “sexual immorality” and he wants to cite Amos, and the words of God as reported by Amos, as words that recognize and refer to an identical category. Thus Keller hopes to cite Amos 2:7 as biblical support for his own notion of “sexual immorality” — much of which is, unacknowledged and perhaps unrealized by Keller himself, wholly a product of “modern political ideologies.”

Look closely at how the trick is performed. Amos 2:7 does not condemn “sexual immorality” in the abstract. What this verse condemns, rather, is “a man and his father go in to the same girl.”

This oddly specific concern isn’t something I imagine would be near the top of the long list of things Tim Keller wants to categorize as “sexual immorality.” But by translating that specific condemnation into a wide-ranging abstraction, Keller is able to pretend that Amos is specifically condemning all of the things he wants to toss into that category.

Same-sex marriage, for example, is something Keller would place into the magician’s cabinet category of “sexual immorality.” Amos doesn’t mention that, but if we translate Amos’ condemnation of “a man and his father” sharing a sexual partner (consecutively or concurrently?) into a condemnation of “sexual immorality,” we can then translate it back out of that category and claim that Amos 2:7 specifically condemns same-sex marriage. Or that Amos 2:7 condemns the baptism of queer believers (Take that, Philip!). Or that Amos 2:7 condemns drag queen story hour, or Tinky Winky’s purse, or whatever the hottest obscure moral panic circulating next month on Facebook turns out to be.

The neat thing about this trick is that it’s most effective on the people who are performing it. Hence the over-the-top flourish of Keller’s trying to use Amos 2 to condemn the things his own “modern political ideology” chooses to fixate on while imagining that he is, himself, providing a model of how to consult the Bible as an objective standard — a plumb line, one might say — for condemning the “modern political ideologies” of others.

And it’s actually worse than that. Because the thing Keller is really trying to challenge here in his condemnation of others’ allegedly insufficient condemnation of all that his modern political ideology places in the category of “sexual immorality” is not a competing “ideology,” but a major, insistent theme in the Bible itself.

Look again at Amos’ strangely specific concern with father-son daisy chains. There are echoes of this in numerous places throughout the Bible. This peculiar focus on the shame-inviting practice of a father and son sharing the same woman as a sexual partner shows up in several other places as well, from Genesis to the New Testament epistles. Both Reuben in Genesis and Absalom in 2 Samuel are condemned for sleeping with their fathers’ concubines, although in both of those stories, the sin is portrayed more as dishonoring their fathers than as a form of sexual immorality.

The story of Absalom and David’s concubines is especially ghastly for the “sexual immorality” it does not condemn. David is not condemned for keeping 10 sex slaves in a house — or for imprisoning them for the remainder of their lives after they were exploited by his son “So they were shut up until the day of their death.” And the story seems to regard Absalom’s sin as a property violation, a kind of theft from his father.

In Eugene Peterson’s translation of Amos 2, he presents this father-son business as having something to do with temple prostitutes. Here’s his colloquial “The Message” translation of Amos 2 verses 6-8:

Because of the three great sins of Israel

—make that four —I’m not putting up with them any longer.

They buy and sell upstanding people.

People for them are only things—ways of making money.

They’d sell a poor man for a pair of shoes.

They’d sell their own grandmother!

They grind the penniless into the dirt,

shove the luckless into the ditch.

Everyone and his brother sleeps with the ‘sacred whore’—

a sacrilege against my Holy Name.

Stuff they’ve extorted from the poor

is piled up at the shrine of their god,

While they sit around drinking wine

they’ve conned from their victims.

If Peterson is correct, then the father-son sex story this passage is most like may be the that of Judah and Tamar in Genesis 38. Tamar was Judah’s daughter-in-law, the widow of his son Er. After her husband dies, his brothers and his father are obliged to provide for her, but instead, they only exploit her further. Tamar’s story is a horror show, but it’s got a killer ending. She’s condemned to burn — by Judah himself! — for getting pregnant as a temple prostitute, but then Tamar turns the tables. She proves that Judah himself was the cause of her pregnancy — a hypocrite who was as happy to sleep with temple prostitutes as he was to burn them to death. And she thus forces him to finally fulfill the economic obligations he’d previously tried to deny.

There’s a sense, then, in which this story supports Keller’s assertion that “social injustice” and “sexual immorality” are “of a piece.” But it does so in a way that completely undermines what he intended that to mean. The behavior this story condemns as sexually immoral is condemned as such because it is also a predatory form of social injustice. It doesn’t suggest, as Keller does, that “both sides” are equivalent, but that the two things are intersectional and intertwined.

Something like that seems to be the point of Amos’ reference to the sexual sins of fathers and sons tucked in there amidst his condemnations of those who extort and exploit the poor. The “sexual immorality” of that father and son was — as with David and Absalom, and with Judah and Onan — a consequence of their willingness to, as Peterson’s translation puts it, treat people as things.

“Sin, young man, is when you treat people like things. Including yourself. That’s what sin is.”

That’s not Amos, of course. That’s Granny Weatherwax — a fictional character in 20th-century novels written by Terry Pratchett. But Granny Weatherwax there sounds a lot like Amos and a lot like the Apostle Paul in Romans 13: “Love does no wrong to a neighbor; therefore love is the fulfilling of the law.”

That’s not some “modern political ideology” or some straw-man caricature of a squishy 21st-century Millennial ex-vangelical “deconstructing” biblical sexual ethics. That is biblical sexual ethics.

But surely it’s a lot more complicated than that …

“No. It ain’t,” Granny Weatherwax says. “When people say things are a lot more complicated than that, they means they’re getting worried that they won’t like the truth. People as things, that’s where it starts.”

A Pauline (or Pratchettine) view of sin leads to a very different understanding of the category of “sexual immorality” than the one that Keller’s modern political ideology leads him to imagine is “biblical.” And it leads to a very different use of such categories.

This view of sin also won’t always sit comfortably alongside the strange categories of “sexual immorality” we encounter in some parts of the Bible. If “love is the fulfilling of the law” then David was not dishonored by his son’s rape of his sex slaves. David was dishonored by having sex slaves in the first place. And Absalom was dishonored by treating them as such. The biblical text of that story may not condemn them for sleeping with concubines — the text of that story suggests that, hey, they’re concubines … that’s what concubines are for. But the king and the prince did harm to their neighbors. They treated people as things. That’s sin — both “sexual immorality” and, more gravely, “social injustice.”

This Pauline/Weatherwaxian understanding shows why some category labeled “sexual immorality” cannot be easily extracted from or contrasted with some separate category labeled “social injustice.” In a Venn diagram of “social injustice” and “sexual immorality,” the latter sits entirely within the former.

And, again, nothing about this is really new. The same idea conveyed by Paul and Granny W. is what we see Jesus saying in his riff about gnats and camels, and what we see Amos and Isaiah saying in the very oldest parts of our Bibles.