I want to talk about the nonsense happening at (and to) Grove City College and how a very conservative, Presbyterian school has come to be accused of being a hotbed of Critical Race Theory Bolshevism. But to really appreciate the many-layered weirdness of this business, I want to start at the beginning. Or, at least, near the beginning — with a story that starts in Boston in 1706.

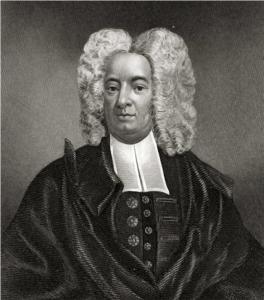

Cotton Mather was then the pastor of North Church in Boston.* The Puritan congregation was so fond of their minister that they presented him with a gift: an enslaved West African man. Mather assigned his new slave the name of Onesimus. We have no record of his real name, the name he was forced to abandon when he was sold to the good Christians of North Church.

Onesimus proved to be — in Mather’s own words — a “pretty intelligent fellow.” And that proved to be a Good Thing for the city of Boston, eventually resulting in countless lives being saved there during the smallpox epidemic that struck the city 15 years later. It’s a remarkable story. Rick Snedeker wrote about it recently at OnlySky — “COVID-19 is Boston’s 1721 smallpox epidemic redux” — and that sent me off, looking for and reading a whole bunch of other articles on this 300-year-old tale of Puritan slavery, disease, African science, and New England superstition.

This is a story that unsettles the legendary version of Cotton Mather most of us acquire from grade school and pop culture. I tend to think of Mather as a creature of the 1600s, someone mainly associated with the Salem witch trials, even if I’m sometimes a bit fuzzy about whether he supported or opposed “spectral evidence,” and what that meant. Yet here is a story in the 1700s, featuring that same Cotton Mather engaging in scientific arguments with members of the Royal Society of London and acting more like a wise and responsible leader than like the Hawthorne villain of my imagination.

But there’s another, larger piece here that doesn’t fit in with the general picture of the Mathers and of New England Puritanism that we learned from school and the movies. In our national mythology, the realm of New England Puritans and Scarlet Letter Calvinists was separate from the southern realm of plantation slavery. But Cotton Mather, like many of the Puritan divines of Boston and Plymouth, was a slave owner who participated in and benefited from stolen labor and human trafficking. (Throughout Cotton Mather’s lifetime, slavery was illegal in the colony of Georgia.)

It was, in fact, the enslaved man Mather regarded as his own property who introduced him to the life-saving practice of inoculation. Cotton Mather and the intellectuals of the Royal Society of London didn’t save Boston from smallpox. An enslaved man named Onesimus did.

As a child in Africa (perhaps Ghana), “Onesimus” had been inoculated himself and had seen the procedure performed on others. The so-called “Dark Continent,” it seems, was generations ahead of London and of Puritan New England when it came to understanding and combating infectious disease. Onesimus taught Mather how to inoculate himself and others against smallpox, and Mather — to his credit — was willing to listen and learn.

That credit is limited, alas, in that Cotton Mather was not also willing to listen to or to learn from Onesimus about the decency and morality of slavery. But I respect that Mather was willing to endure criticism for heeding Onesimus’s advice and for publicly arguing that others ought to do so.

Mather was able to convince a Boston physician to inoculate hundreds of people, demonstrating that the technique dramatically reduced mortality for those it protected from smallpox. The success of Onesimus’s technique led others to adopt it throughout the colonies and back in England, saving countless lives over the next century and contributing, eventually, to the development of Edward Jenner’s vaccine in 1796.

But what we really need to talk about here is that name: Onesimus.

That’s a biblical name. This was fashionable for good white Christians here in America. When we enslaved people and assigned them new names for their lives of bondage, enriching ourselves from their unpaid labor, we liked to display our piety by assigning those people biblical names. Perhaps the most famous example of this is from Alex Haley’s Roots, in which Haley’s ancestor, Kunta Kinte, was forced to accept the slave-name “Toby” — from the biblical Tobias, meaning “God is good.”

The blasphemous irony of this practice is particularly staggering when it was done by slave-owning white theologians — men who fully understood all the bitter resonances of the biblical names they assigned to the people they enslaved. Charles Hodge enslaved a man he renamed “John.” Was that name meant to be a reminder of the beloved disciple? Or was it meant to refer to the author of 1 John? Or perhaps to the liberationist visionary of Patmos? Any of those would be cruelly obscene, so it hardly matters which.

Jonathan Edwards renamed the enslaved people he purchased Titus, Susanna, and Joseph. The first is the name of the uncircumcised foreigner who became a Christian bishop, the second is the name of a righteous captive living in Babylonian exile, and the third is the name of the man who helped Pharaoh enslave the entire known world — creating the context for the defining events of Exodus. The venomous absurdity of all of those names couldn’t have been unnoticed by someone like Edwards.

Cotton Mather, likewise, surely understood the vicious cruelty and hypocrisy of his imposition of the name Onesimus.

That comes from the book of Philemon. Onesimus was both the subject and the bearer of that epistle from the apostle Paul. It’s a pointed and to-the-point letter — just 25 verses, a single page with a singular focus. Onesimus was a fugitive slave and he was returning to his former “master,” Philemon, who would have to decide whether to re-enslave him or to welcome him back as a brother and an equal. Cotton Mather — who was a pretty intelligent fellow himself — could not have missed the point of Paul’s letter, which is that Paul wasn’t really giving Philemon any choice at all when it came to Onesimus, his brother in Christ.

Mather may have read John Calvin’s commentary on Philemon. Calvin’s perspective isn’t entirely coherent there. His commentary is frequently distracted by strained devotional tangents, and when he focuses on the question of slavery itself it can be deeply problematic (to be generous). But for all of that, Calvin recognizes that both Philemon the person and the readers of Philemon, the scripture, are presented with a clear and overwhelming case for recognizing Onesimus as a brother and an equal, no longer as a slave.

Mather was a Puritan and a Calvinist, but he lived 150-ish years after Calvin wrote that commentary. The modern slave trade already existed in Calvin’s time, but he was not personally involved or invested in it the way that Mather and the entire Massachusetts Bay Colony were. As the article linked above discusses, Calvin didn’t seem to know much about the modern slave trade and most of what he imagined he knew about slavery in first-century Rome was wrong. (Calvin’s understanding of first-century Roman slavery was about as reliable as his understanding of first-century Judaism — which is to say it was wildly and weirdly misleading, at best.)

The passage of that 150 years and white Calvinists’ deepening investment in the modern slave trade changed the way that Calvin’s theological heirs understood the story of Philemon. The reformer himself saw it as an obvious and insurmountable obstacle to any notion of “Christian slavery,” but the Christian slave-owners and Christian slave-traders who otherwise followed his teachings had already begun reinterpreting the story to twist it into something very much the opposite. Over time they transformed that story into one they regarded as a clobber-text affirming their white Christian right to enslave others — an implausibly strained and twisted reading that would have baffled Calvin, Philemon, and Onesimus, and that would have enraged Paul.

White Calvinists, when forced to choose, proved more committed to whiteness than they were to Calvinism. Both of those things — whiteness and Calvinism — were still relatively young when Cotton Mather was born in Puritan Boston. But by the time he was serving as pastor of North Church, a century and half of shackles and chains had already elevated the former over the latter to the extent that he could blasphemously assign that name Onesimus without fearing the righteous wrath of “the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.”

Fast forward another 300 years and white Calvinism seems even more deeply confused about which is which. And that brings us back to Grove City and the weird spectacle of “conservative” Presbyterians explicitly rejecting everything Calvin taught about human nature and sin.

We’ll pick up the story there in a bit. (It’s warm and sunny here in Chester County and all that mulch ain’t gonna stack itself.)

* This was the old “North Church,” not to be confused with the Old North Church that would later become famous for “One if by land, two if by sea.” To avoid confusing the two, this first North Church is sometimes referred to as Second Church, which isn’t actually very helpful.

The nothing-to-do-with-Paul-Revere North Church became Unitarian in the 1800s, but it began as a Puritan congregation led by Increase Mather, then by his son, Cotton Mather, and still later by his son, Samuel Mather. I can’t complain that this sounds like nepotism since Samuel was eventually succeeded by John Lathrop, the great-great-grandson of John Lowthorpe, who is an ancestor of mine.

Lowthorpe may well be an ancestor of yours, too, actually, since the guy had 14 children 400 years ago on both sides of the Atlantic and that makes him a branch in a whole lot of family trees.