From August 8, 2011, “On the road to Weehawken”

Back in 2011, Rick Warren said something dumb — something perniciously dumb, corrosive, and destructive. He said that caring for people in poverty is the responsibility of the church … so far so good … and therefore it is not the responsibility of the state. Ugh.

That’s dangerous nonsense that threatens several different things I care about: the gospel, the Bible, the Baptist tenet of separation of church and state, the Gettysburg Address, healthy communities, justice, democracy.

So I responded by noting that centuries of Christian thought and teaching, as well as Moses and the prophets, has always taught that “Responsibility is differentiated, mutual and complementary, NOT exclusive, binary and competitive” and posted that phrase 10 times, with each iteration linking to a discussion of “subsidiarity” or of “sphere sovereignty” or of “the inescapable network of mutuality,” all of which highlighted the various forms of foolishness and injustice that flowed, inevitably, from Warren’s notion of “exclusive, binary, and competitive” responsibility for justice, welfare, and the common good.

That resulted in a squadron of flying monkeys from Warren’s Saddleback Church flapping through the comment section here to angrily defend their leader and his vision of exclusive, binary, competitive nuttery. I responded to this drive-by trolling from the mega-church here — “Subsidiarity and Saddleback” — pointing out that, thankfully, none of those folks actually fully believed what they were saying.

My argument there, alas, uses words like “subsidiarity” and “differentiated” and “complementary” and I’d probably have been better off just replying with this old joke:

Early one morning a man turned up at the house of his minister in tears, saying, “Please, can you help. A kind and considerate family in the area is in great trouble. The husband recently lost his job, and the wife cannot work due to health problems. They have three young children to look after, and the man’s mother lives with them because she is unwell and needs constant care. They have no money at the moment, and if they don’t pay the rent by tomorrow morning the landlord is going to kick them all onto the street, even though it’s the middle of winter.”

The minister replied, “That’s terrible. Of course we will help. I will go get some money from the church fund to pay their rent. Anyway, how do you know them?”

To which the man replied, “Oh, I’m the landlord.”

An old joke would’ve been more appropriate, since our visitors from Saddleback were, themselves, mainly insisting on their own variation of an even older joke, retelling the Saddleback Approved version of the parable of the Good Samaritan in which first a mayor, then a congressman “pass by on the other side” without helping the injured man and everyone from Rick Warren’s church cheers and says, “Damn straight! You’d better not interfere — that’s the church’s responsibility not yours, you Big Government Tyrants!”

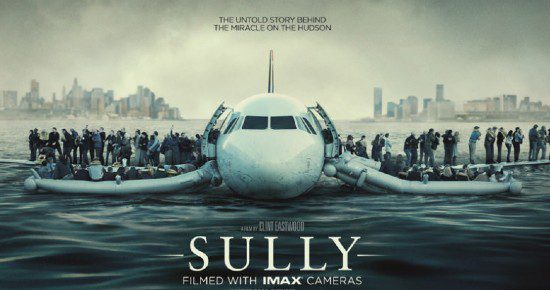

But instead of a joke or a story, I responded to our anti-neighborly neighbors from Saddleback with the discussion of a real life variation of Jesus’ parable, in which a certain Airbus fell among birds on the flight from New York to Charlotte. …

Or consider the role and duty of a ferry boat captain. Her job is to pilot a ferry boat from Point A to Point B and back again according to schedule while ensuring the safety of her passengers. That is her primary responsibility. It’s what she was hired to do and what she is paid to do.

That duty and responsibility means that she must not stray from her assigned route. Any such deviation will put her ferry and its passengers off schedule. It could also expose her passengers to added risk, endangering their safety and thus betraying her duty as ferry boat captain.

But one day not too long ago, several ferry boat captains did exactly that. With little thought for their unchanging daily duty, they turned their boats around and, instead of taking their passengers safely to shore in a timely manner, they carried them to the middle of the river.

They did this because Capt. Chesley Sullenberger, the pilot of US Airways Flight 1549, had just landed his Airbus 320 right there, on the surface of the Hudson River.

Ferry boat Capt. Brittany Catanzaro was not hired to rescue airline passengers from the river. That was not her job. She wasn’t hired to do that and she wasn’t being paid to do that. She was responsible for the passengers aboard the NY Waterways ferry Thomas H. Kean, and not for the passengers of US Airways Flight 1549. Those passengers were US Airways’ responsibility. And water rescue is the job of the Coast Guard or of the FDNY or NYPD.

I’m not sure exactly where in the Hudson Capt. Sully touched down, actually. He may have been closer to the Weehawken side of the river, in which case the stranded passengers perched on the slowly sinking airplane would have fallen under the jurisdiction of New Jersey’s rescue personnel.

None of those responders, however, hesitated for even a second that day to consider such jurisdictional niceties. They all sprang into action without any thought as to who might bear specific or exclusive responsibility for the people stranded in the river.

The very idea of “exclusive responsibility,” in fact, would have seemed horrifying.

Capt. Catanzaro and Vincent Lombardo, captain of another NY Waterways ferry, arrived at the plane within just a few minutes of its touching down in the river, followed soon after by Circle Line ferries and FDNY marine units. They all responded so quickly because they all knew — by training, or by instinct, or by virtue of just being human — that it’s foolish to debate over jurisdiction, or to imagine that the responsibility to act belonged only to one agency and not to any other.

The passengers on that slowly sinking plane were headed to Charlotte and then, from there, to Seattle and to whatever business awaited them in those places. They had no previous relationship to the ferry boat captains or to the passengers on those ferries before Capt. Sully expertly splashed his plane down onto the river on which they were floating. And after that crazily beautiful landing, the only relationship they all shared was that of the crudest most basic kind — a shared humanity and physical proximity.

But that basic relationship was enough for the people on those ferries to recognize, instantly, that it made them responsible. It was enough, even, for them to put every other responsibility they had on hold. No one boarded those ferries expecting to spend the rest of their afternoon plucking strangers out of the water. That wasn’t their job. Like the Samaritan in Jesus’ story, those people had places to be and jobs to do. They were just trying to get to Manhattan or to Weehawken so that they could get on with whatever those other duties and responsibilities were.

But then their circumstances changed and thus their responsibilities changed, because they knew that’s how it works.

It would have been wrong for those commuter ferries and sight-seeing boats to “pass by on the other side.” It would have been wrong to tell themselves that those soaked and sinking strangers were the exclusive responsibility of someone else — the Coast Guard, the FDNY or US Airways — and not their responsibility too. Because (go ahead, say it with me) responsibility is never exclusive, binary and competitive. It’s always mutual and complementary.

We all know this in extraordinary situations, but somehow we tend to forget it in our ordinary lives. Sometimes we choose to forget it because, after all, we have places to be and our own jobs to do, and we imagine that our own lives will be easier if we could somehow exclude ourselves from mutuality.

But mutuality makes our lives easier, not harder. Mutuality isn’t a burden. “Bear one another’s burdens,” the apostle Paul wrote. But some selfish, reptilian part of our brains recoils at the idea — I’m having enough trouble bearing my own burdens, thankyouverymuch. The last thing I need is to get saddled with everyone else’s too. I’m just trying to get to Jerusalem or to Weehawken. I’ve got enough on my plate as it is.

And thus we avoid helping and we avoid being helped. And then we construct ridiculous intellectual justifications for this rejection of mutuality. “Either/Or!” we declare. “Never Both/And.”

Extraordinary circumstances can break through our protective shell and remind us that we know better, and that we can be better and act better and live together better in a better world.

I just wish it didn’t take an Airbus 320 splashing down out of the sky to remind us of that.