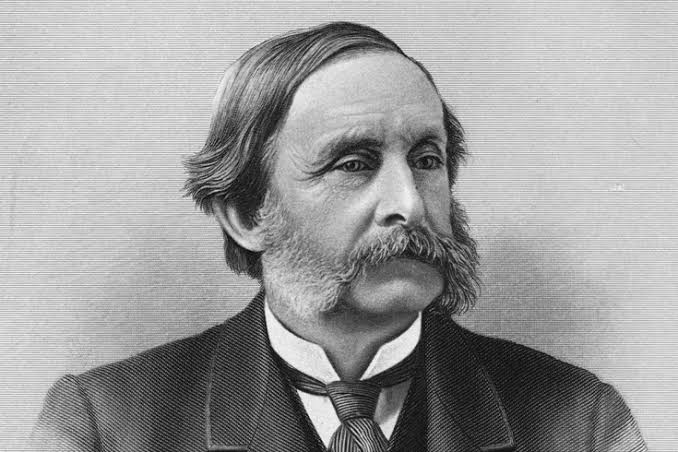

With the current editor of the Atlantic magazine in the news, I’m thinking today of Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who was a writer and editor for the magazine for several decades in the 1800s.

Higginson is remembered today — to the extent he is remembered — for two very different things. The first involves the poetry of Emily Dickinson. In that story, he comes across as somewhat stodgy and stiff and starched. He was the first editor or publisher to encounter Dickinson’s poetry after she sent him four poems with a letter that asked “Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?” He responded with encouragement, but also with some criticism of her unconventional style. He had never seen anything like what he was reading — no one had — and it shook him.

Higginson and Dickinson became regular correspondents and he became a kind of literary mentor to her, even though her Verse was alive in ways that left him confused and maybe even a little frightened.

So that’s the first Thomas Wentworth Higginson story. He was the first editor to publish Emily Dickinson’s poems, but he was also the editor who rejected many of her poems, which makes him seem like a somewhat comical stick in the mud. It makes him seem like the sort of guy who would choose to go by “Wentworth” rather than “Tom” (which he did). Or like the kind of New England Unitarian minister who advocated for Temperance and homeopathy (which he also did).

But alongside the story of T. Wentworth Higginson, semi-successful literary editor there is also the other story, of Higginson the activist. Higginson was an abolitionist who preached sermons and gave speeches denouncing slavery. This involved exactly the sort of mutton-chopped 19th-century oratory you may be imagining but, in Higginson’s case, it also involved things like running guns (and even cannon) to abolitionist settlers in Kansas. He was also one of the “Secret Six” who raised the money for John Brown’s raid at Harper’s Ferry.

And Thomas Wentworth Higginson, former Unitarian minister and future literary editor, also helped lead the attempted rescue after the Kidnapping of Anthony Burns. Burns had been a slave in Virginia before he escaped to Boston in March of 1854:

This new-found freedom, however, would be short-lived. Soon after his arrival he sent a letter to his brother, who was also a slave of Charles Suttle. Even though the letter was sent by way of Canada, it found its way into the hands of their master.

A few years earlier, Suttle could have expected little help from a northern state in recovering a fugitive slave. Nine states had personal liberty laws declaring that they would not cooperate with the federal government in the recapturing of slaves. But with the recent passing of the Fugitive Slave Act, a component of the Compromise of 1850, the law was on Suttle’s side.

Suttle travelled to Boston to claim his “property,” and on May 24, under the pretext of being charged for robbery, Burns was arrested. Boston abolitionists, vehemently opposed to the Slave Act, rallied to aid Burns, who was being held on the third floor of the federal courthouse. Two separate groups met at the same time to discuss Burn’s recapture: a large group, consisting mainly of white abolitionists, met at Fanueil Hall; a smaller group, mostly blacks, met in the basement of the Tremont Temple.

The meeting at the Tremont Temple was quickly over. Those present decided to march to the courthouse and release Burns, using force if necessary. The meeting at Fanueil Hall lasted much longer. The group there debated the course of action. When the intentions of the Tremont Temple gathering were announced, however, the meeting abruptly ended. About two hundred citizens left Fanueil Hall and headed to the courthouse.

The crowd outside the courthouse quickly grew from several hundred to about two thousand. A small group of blacks, led by white minister Thomas Wentworth Higginson, charged the building with a beam they used as a battering ram. They succeeded in creating a small opening, but only for a moment. A shot was fired. A deputy shouted out that he had been stabbed, then died several minutes later. Higginson and a black man gained entry, but were beaten back outside by six to eight deputies.

Boston inhabitants had successfully aided re-captured slaves in the past. In 1851, a group of black men snatched a fugitive slave from a courtroom and sent her to Canada. Anthony Burns would not share the same fate. Determined to see the Fugitive Slave Act enforced, President Franklin Pierce ordered marines and artillery to assist the guards watching over Burns. Pierce also ordered a federal ship to return Burns to Virginia after the trial.

Burns was convicted of being a fugitive slave on June 2, 1854. That same day, an estimated 50,000 lined the streets of Boston, watching Anthony Burns walk in shackles toward the waterfront and the waiting ship.

A black church soon raised $1300 to purchase Burns’ freedom. In less than a year Anthony Burns was back in Boston.

When human beings are snatched off the street and shipped away to slavery, Higginson believed, one was obliged to get a battering ram.

I have not read any of his own poetry, but I will say that the Verse he wrote with that battering ram is, still, alive.