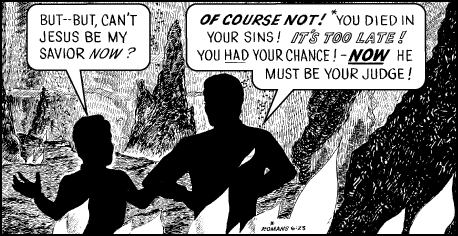

Rob Bell’s book Love Wins: A Book About Heaven, Hell and the Fate of Every Person Who Has Ever Lived went on sale yesterday and the backlash and criticism hasn’t yet peaked.

The more I read of this criticism, the more I’m struck by the way everything Team Hell is upset with Bell about, or accusing him of, could be said even more strongly of St. Paul. The doctrine of Hell, they say, is so central and essential to Christianity that anyone who fails to embrace this specific dogma regarding “eternal punishment” is “dangerous and contrary to the word of God.”

So allow me again to repeat everything that Paul had to say about the doctrine of Hell:

…

…

Nothing. Nada. Zip. The earliest writings in the New Testament never mention this allegedly central and essential doctrine. Nor do the books we call the Old Testament, but which Paul just referred to as “the scriptures.”

And it’s not just that Paul is wholly silent, he also takes a very dim view of anyone who suggests that he left anything out of the gospel he preached. This is it, he said repeatedly, this is the gospel and nothing other than this and nothing more than this. I have not left anything out. Anyone who adds to it, he said, should be “accursed.”

He didn’t say they were going to Hell, mind you. Because Hell was not a part of his gospel — it was something he left out, an omission later correct by those who felt the gospel Paul preached was insufficient and incomplete.

Bell’s argument — from what I’ve seen thus far — is compatible and congruent with our understanding of the gospel Paul preached. Team Hell oddly insists that its own gospel is not, but that it corrects what they see as the defect in Paul’s teaching — the Bellishly deviant omission of the central and essential doctrine of Hell.

* * * * * * * * *

The great church historian Martin Marty has taken note of this most recent recurrence of the perennial debate between Team Hell and its dissidents. His take is a bit sardonic, as though he’s seen it all before (which, of course, he has):

The Michigan pastor-author is not alone; Bell’s hell is paralleled in treatments of a whole wing of evangelicals. Some of this group “out” themselves, while others are in a kind of purgatory of inference that they are not quite orthodox on the subject. What this second wing keeps pondering and sometimes proclaiming is that there are ways to witness to the fact that God is holy and just, other than saying that he takes delight in punishing those ignorant of the stakes or those who are players of other salvation games. …

Formal theologians in the evangelical camp are bemused by the consistent polls in which only a small percent of the clergy are ready to affirm and preach doctrines and threats of hell and the large percent of their followers who are not. They know of the gap, and feel they must close it. Otherwise orthodoxy will disappear and relativism or universalism will win. The evangelical parents whose teenage “good kid” son who has not made a formal profession of faith in Christ and thus will be condemned to hell if he dies, need better reasoning than the dogmatic professors of hell give them.

Otherwise, this latest fissure in evangelicalism will grow, and arguments will distract preachers of hell from their tasks and opportunities to win people from its brink, thus swelling its population in the interest of saying the right thing about this form of a holy and just God’s mode of everlasting punishment.

* * * * * * * * *

Rob Bell had a book-launch event yesterday, streamed online, in which he discussed Love Wins with Newsweek religion writer Lisa Miller. Timothy Dalrymple has posted a transcript of that conversation.

What I find refreshing is how relaxed this conversation is, how at ease and unguarded Bell’s responses are despite his knowing that his every word will be parsed and picked apart and sniffed at for the scent of heterodoxy. One gets the sense that these are his thoughts and his answers and that he does not change them or spin them depending on who might be listening or listening in. That’s not usually the sense one gets of the guarded language employed by the parsers and pickers and sniffers themselves.

My favorite bit in that book-launch discussion comes at the end, in which Bell describes his pastoral concern for people who have been taught to fear a cruel or abusive God:

… my experience as a pastor, answering real questions from real people, is that lots of people have really really really toxic dangerous, psychologically devastating images of God in their head. Images of a God who’s not good. So my experience has been, lots of people go to church, they sing the songs, they hand out the pamphlets, they really want … but to be honest, deep down they have profound ambivalence about God. So we can talk about the Bible, we can talk about Heaven and Hell, we can discuss all this, but at its core – the question behind the question behind the question, the mystery behind the mystery behind the mystery – they have a view of a God who is terrible, that they can’t even imagine being loving, or wanting anything to do with.

And over and over and over again, I’ve interacted with people who … you end up with them saying, “Actually, I think the universe might be a really awful place. It might be terribly unsafe. God might be like my abusive father.” So I think it’s really important that we talk about this because what happens is, sometimes people are talking about good news, they’re talking about Jesus, and yet you’re smelling the God behind it, going “Whatever you’re talking about, the God behind that, I can’t trust, is not good.” So in some senses, God being good is such a fresh, radical, new idea.

There is a woman who comes up to me every Sunday at our church. She hands me a piece of paper. It’s half of an 8-by-11 sheet, and it’s folded in half. She walks away. We smile, I give her a hug, we talk for a moment, and she walks away. And on the sheet of paper is a number, and it is the number of days since she last cut herself. She told me about a year ago that every man she’d ever been with hit her. So when she hears about love, her experience of life has not been love. And just a couple weeks ago, she crossed the 365-day mark. So we brought her up on stage and I introduced her and said this is her name and she’s celebrating one year without cutting herself. And it was a beautiful, beautiful moment, to say the least.

But for her, it’s like a whole new rewiring of her heart and mind is going on. And that’s what all of this means to me. I love the discussion, I love the speculation, I love all the different theories, but ultimately for me its like, I don’t want her to cut anymore. It’s, like, that simple. I want to see her experience good news. I want her to experience love. I don’t want her to live with these sorts of images and messages she’s been sent about who God is and what life is ultimately like and whether the universe is even a place that she can call home. I want her to give me another sheet of paper, and I want us to get to two years.