Nicolae: The Rise of Antichrist; pp. 238-241

Buck Williams and Tsion Ben-Judah are riding through endless fields of flowers and grains the Israeli desert, chatting about what a stupendously terrific guy Buck Williams is — brave, selfless, spiritually mature.

This may seem unrealistic at first. Most people, in real life, are not greeted with such constant, effusive praise from everyone they encounter. Most people, in real life, would find it unbearably awkward to offer or to receive such gushing adulation. But I think the authors realize this. They’ve included these endless scenes in which other characters heap praise on their heroes to remind us that Buck and Rayford are not like most people. They’re exceptional. They’re special — so special that others feel compelled to remark on what wonderful people they are and so special that they’re able to accept this praise as their due.

In this scene, Tsion takes a bit of prompting, but Buck subtly reminds him of his role as a supporting character, and he quickly responds with the customary praise for our hero:

“Tsion, far be it from me to advise you spiritually. You are a man of the Word and of deep faith.”

Tsion interrupted him. “Do not be foolish, my young friend. Just because you are not a scholar does not mean you are any less mature in your faith.”

This is not just Tsion’s encouragement for Buck, but also the authors’ encouragement for you, gentle reader. You may not have spent years poring over premillennial dispensationalist charts and graphs, like the great scholar Tim LaHaye — a man of the Word and of deep faith, but that does not mean that you are any less mature in your faith. You’re reading this book, aren’t you? And, more importantly, you purchased this book — which means you, dear reader, have spiritual maturity coming out the wazoo.

But enough about his spiritual maturity, what about Buck’s bravery?

“I wish I could do something tangible for you, Tsion,” Buck said.

“Tangible? What is more tangible than this? You have been of such encouragement to me that I cannot tell you. Who else would do this for a man he hardly knows?”

No one. No one else would be so brave. Well, other than Rayford, of course.

And did we mention that Buck Williams is also sensitive? The authors remind us of this as well by having Buck commend Tsion for his tears.

“At least you have been able to cry. Tears can be a great release. I fear for those who go through such trauma and find it impossible to shed tears.”

Real manly men cry. Really, really manly men — like Buck Williams — don’t actually cry themselves, but they’re man enough to praise other real men for doing so.

Tsion sat back and said nothing. Buck prayed silently for him. Finally, Tsion leaned forward again. “I come from a heritage of tears,” he said. “Centuries of tears.”

Because Judaism, of course, is hundreds of years old.

I don’t want to read too much into that one phrase, but consider again what is happening right now in this story. Buck and Tsion are fleeing Israel because the Jews have violently rejected Tsion’s belief that Jesus of Nazareth is the Messiah. That idea is what drives the subplot at the center of this book. And when Tsion reflects here on his “heritage of tears,” that is what he is talking about.

He’s not talking about slavery in Egypt, the cycles of conquest in Judges, Babylonian exile or all the many ancient persecutions embodied by Haman in the book of Esther. He’s only talking about recent “centuries of tears” — those A.D. centuries tracing back only as far as when, in Tim LaHaye’s theology, all the troubles began for the Jews: Their failure to recognize and embrace Jesus as their Messiah.

That doesn’t just drive this particular Tsion-fleeing-Zion subplot. It’s a centerpiece of LaHaye’s whole End Times belief system, which culminates in Armageddon and the mass-slaughter of Jews. For that scheme to make sense, these people must deserve such a cruel fate, and End Times “Bible prophecy scholars” trace that desert back to the guilt uniquely incurred, they say, by the Jewish rejection of Jesus as Messiah. Back in 2007, John Hagee — who’s like Pepsi to LaHaye’s Coke in the world of PMD End Times book sales — got booted from a symbolic post with the McCain campaign for stating all of that a bit too directly.

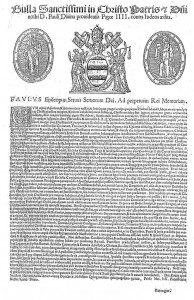

To be clear, this anti-Semitic teaching predates the modern invention of Rapture-mania and “Bible prophecy scholarship.” You can find the same logic, for example, in Cum nimis absurdam, the notorious 16th-century papal bull issued by the unblessed Pope Paul IV, which begins: “Since it is completely senseless and inappropriate to be in a situation where Christian piety allows the Jews (whose guilt — all of their own doing — has condemned them to eternal slavery) access to our society and even to live among us …” That’s the same idea — “centuries of tears” brought on by “their own doing.”

This is perhaps the only part of Tim LaHaye’s “prophecy” that hasn’t utterly failed, but that’s only because it is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Christians teach that Jews deserve to suffer and then those same Christians make Jews suffer. Lather, rinse, repeat — centuries of tears.

But while End Times “prophecy scholars” didn’t invent this ugly, anti-Semitic theology, they’re the ones most actively keeping it alive today. It’s been a long time since popes have called for ghettos or for the destruction of the Talmud, but here in these best-selling novels, we are reminded again and again that the evil Jews who murdered Tsion’s family are condemned by guilt all of their own doing.

Have I mentioned lately that these are the World’s Worst Books? These are the World’s Worst Books.

But let’s get back to Buck Williams and how exceptionally special he is.

“Cameron, there is something you can do that would be of some comfort to me.”

“Anything.”

“Tell me about your little group of believers there in America. What did you call them? The core group, I mean?”

“The Tribulation Force.”

“Yes! I love hearing such stories. Wherever I have gone in the world to preach and to help be an instrument in converting the 144,000 Jews who are becoming the witnesses foretold in the Scriptures, I have heard wonderful tales of secret meetings and the like. Tell me all about your Tribulation Force.”

This is how we know that Tsion Ben-Judah is going to fit right in as the newest member of that Tribulation Force. He doesn’t want to hear about any of the other believers there at New Hope Village Church. Who cares about them? They’re not important. They’re not special. All he cares about is “the core group” — that elite special group of special people who mean so much more to everyone than any 144,000 singing virgins.

He’s just like Bruce Barnes. After the Rapture, Bruce was transformed from the worst visitation pastor in Illinois to the worst senior pastor in the state. His church was overflowing with new converts — a growing flock in desperate need of a shepherd. But Bruce had no time for any of them. Hundreds of new believers still wrestling with the loss of their children and other loved ones were left to fend for themselves as Bruce spent all of his time huddled behind a locked door with the only three members of the church he cared about.

As Buck begins re-telling the story of the Tribulation Force — i.e., as Jerry Jenkins pads out another full page with a bland summary of the Story So Far — he’s struck by how much Tsion reminds him of Bruce:

Tsion did not know yet of the death of Bruce Barnes, a man he had never met but with whom he had corresponded and with whom he hoped to minister one day. …

“I cannot wait to meet him,” Tsion said. “I will grieve for my family, and I will miss my mother country as if she truly were my parent. But to get to pray with your Tribulation Force and open the Scriptures with them, this will be balm for my pain, salve for my wound.”

Buck took a deep breath. He wanted to stop talking, to concentrate on the road, on the border ahead. Ye he could never be less than fully honest with Tsion.

That’s true — except for the bit earlier in this same chapter where Buck spent three pages dodging Tsion’s direct questions about whether or not poor Jaime, his limo driver, was still alive.

“You will meet Bruce Barnes at the Glorious Appearing,” he said.

Buck peeked in the mirror. Clearly, Tsion had heard and understood. He lowered his head. “When did it happen?” he asked.

Buck told him.

“And how did he die?”

Buck told him what he knew. “We’re probably never going to know whether it was the virus he picked up overseas or the impact of the blast on the hospital. Rayford said there seemed to be no marks on his body.”

“Perhaps the Lord spared him from the bombing by taking him first.”

That’s a strange comment from Tsion, who just a few pages earlier was reassuring himself that death by sudden explosion was a form of mercy for poor damned-to-Hell Jaime. It’s an odd form of consolation: “Perhaps the Lord spared him from the bombing” by killing him with an exotic virus first. Or perhaps the Lord spared him from the virus by killing him with the bomb first. Either way, the Lord clearly spared him from, say, being gnawed to death by fire ants.

This makes sense to Buck and Tsion and the authors because it’s the same logic at work in their death-denying belief in “the Rapture.” The authors think it would have been horrifying if Irene Steele, little Raymie and the Rev. Vernon Billings had all instantly dropped dead from simultaneous aneurysms. The Rapture, the authors say, spared them from any such death. But for those being Raptured, I don’t understand how the experience or the outcome would be any different. Either way, in the twinkling of an eye, they never saw what hit ’em.

The authors should also be more careful here about using phrases like “taking him” to refer to death. Such language is too close to the very same verses of the Bible they claim teach the Rapture:

For as in the days before the flood, they were eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage, until the day that Noah entered the ark, and did not know until the flood came and took them all away, so also will the coming of the Son of Man be. Then two men will be in the field: one will be taken and the other left. Two women will be grinding at the mill: one will be taken and the other left.

It’s no good for the authors if readers of these books start to think, “Hmmm, it almost sounds there like being ‘taken’ is actually a bad thing. And if getting ‘left behind’ is what happened to Noah, then that sounds like a good thing. It almost seems like all these verses LaHaye says are about the sudden, inevitable coming of the Rapture are really about the sudden, inevitable coming of death.”

That’s not really a train of thought the authors can afford to encourage.