Historian Jelani Cobb, dean of the Columbia Journalism School, was on Chris Hayes’ MSNBC show last week discussing the mass-deportation raids by Trump’s ICE goons and the overwhelming grassroots civic opposition to them in communities all over America.

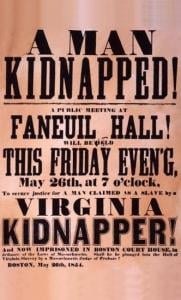

Cobb compared both the raids and the community defense in response to them to the widespread backlash to similar actions by federally deputized slavecatchers and kidnappers following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850.

Cobb compared both the raids and the community defense in response to them to the widespread backlash to similar actions by federally deputized slavecatchers and kidnappers following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850.

We’ve discussed this parallel here quite a bit, focusing on things like the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue and the kidnapping of Anthony Burns in Boston.

But Cobb makes the case that people like the Oberlin rescuers were not typical of the opposition and resistance to the slavecatchers. Most of the people who rose up in opposition to those abductions by federally sanctioned goon squads were not radicals or abolitionists or activists. They were, Cobb says, simply neighbors.

I haven’t been able to find a video or a transcript of the entire conversation, but here’s the key snippet from a BlueSky post:

@jelaniya.bsky.social on historic parallels to the reaction to ICE raids:"My students are like, 'Oh, so these people who came out against the Fugitive Slave Act were all abolitionists?' I said, 'No, these were people who could not countenance the idea of their neighbors being taken from them.'"

— All In with Chris Hayes (@allinwithchris.bsky.social) 2025-06-20T01:05:25.714706Z

Here’s my handmade transcript of that:

COBB: When I talk with my students about the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and how it pushed the nation closer to the brink of Civil War, because they began snatching people out of communities — people who had lived in communities, people who had escaped slavery. And so my students are, like, “Oh, so these people who came out against the Fugitive Slave Act were all abolitionists.” And I said, “No. These were people who could not countenance the idea of their neighbors being taken from them. …

The fundamental civic unit in this nation is neighbor, and that is the people who live in your community. Are you prepared to see them treated in this way? And people simply were not.

HAYES: I think the civic response to what we’re seeing there is very encouraging, in the same way, right? That, as an abstraction, I support mass deportation. Get ’em all out of here. As a reality … your neighbor.

COBB: Your neighbor.

Here, as ever and as always, the most important question is the one asked 2,000 years ago by an unnamed Bible scholar talking to Jesus of Nazareth: “Who is my neighbor?”

Cobb’s shorthand answer to this — “the people who live in your community” — is headed in the right direction because he’s suggesting it means all of the people who live in your community. All. Of. Them.

Cobb’s shorthand answer to this — “the people who live in your community” — is headed in the right direction because he’s suggesting it means all of the people who live in your community. All. Of. Them.

But it also means all of the people who live in the next community over, and the one past that, and the one past that, and in every other community anywhere.

The answer to the question “Who is my neighbor?” is always Everyone.

But that wasn’t quite the answer that Jesus himself gave in response to that question. His answer was in the form of a story, a parable, a question thrown back at the question. “A certain man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, when he fell among thieves …”

Jesus’ answer to the question “Who is my neighbor?” was “Be a neighbor.” Be a neighbor to everyone and everyone will become a neighbor to you.

That’s an indirect answer to the question because “Who is my neighbor?” is always the wrong question and you can’t give a right answer to the wrong question.

The question, as always, is an attempt to find a loophole or an escape clause. Whenever we ask “Who is my neighbor?” what we really mean is “Who is not my neighbor?” or, less tactfully, “Can’t you please just tell us that there’s somebody we’re allowed not to love?”

Usually in American politics this loophole-seeking, always wrong, but always at the heart of things question “Who is my neighbor?” is framed around the Constitution rather than the Gospels. It’s not “Who is my neighbor?” but, rather, “Who is ‘We, the people’?” Who counts as “we” and who counts as “people”? And who doesn’t count? And who are we allowed not to count? And can’t you please tell us that there’s somebody we’re allowed not to treat as people?

The same rule applies to this constitutional argument as applies to all of those Jesus stories. You never want to be the guy asking those loophole-seeking questions. The guy looking for loopholes is always the Bad Guy in those stories.

Stop asking the wrong questions and just be a neighbor.