In two recent posts, I discuss Abu Musab Zarqawi's terrorist training camp at Khurmal, in northern Iraq, which was discovered, but not disturbed, in early 2003.

The camp at Khurmal presented:

A. A legitimate military target in an already declared, justifiable war that was being waged with the full approval and cooperation of the "opinions of mankind;"

B. A military target isolated from nearly all entanglements with the non-combatant civilian populations;

C. A military target located in the northern no-fly zone, a region placed by the United Nations under the military jurisdiction of an international coalition led by the United States and the United Kingdom.

Given those three conditions, I echoed Sen. Biden's queston from Feb. 2003: Why didn't we take out this target?

My angry Jacobin friend Josh doesn't address this question, but in comments to this post he fires off a series of questions premised on the idea that not all of these conditions were true.

He takes issue with condition A, characterizing the war on al-Qaida as some kind of unilateral, neo-isolationist enterprise. (Anyone who seriously thinks the war on al-Qaida is based on a Buchananite chauvinism that sees only American lives as valuable ought to look again at the nationalities of those killed in the World Trade Center.)

I can't follow all the leaps Josh takes here, but part of what he seems to suggest is that wars of self-defense occupy a lower moral plane than interventionist wars on behalf of others.

It's an intriguing inversion of just-war teaching. Thus, for Josh, the invasion of Iraq — which he argues was necessary due to the threat Iraq posed to Israel — has a higher moral purpose than the self-interested war of self-defense against al-Qaida. (Josh goes further — to argue that the threat al-Qaida posed to the U.S. was "far more benign" than the threat Saddam Hussein posed to Israel. Whew.)

It might follow then that it was appropriate to undermine the war against al-Qaida — by, in this instance, refraining from action against the Khurmal facility in order to preserve it as part of the case for invading Iraq — if doing so helped to advance the more noble-minded humanitarian war in Iraq. This would be, for Josh, a demonstration of "a concern for human rights that transcended national borders" untainted by the worldly self-interest of the war against al-Qaida.

I disagree on matters of both fact and principle. Al-Qaida poses a real and grave threat — to America, to Israel, to the entire world. And as Charles Duelfer reconfirmed this week, Iraq has posed little threat to the region or to the world since 1991.

I also believe, as a proponent and adherent of the just-war tradition, that the burden of proof for justifying a war waged in self-defense is lighter than that for an interventionist humanitarian war.

This does not even come close to suggesting that people in other countries "don't count." I believe that interventionist actions can be justified — as I have argued in the case of President George H.W. Bush's action in Somalia; President Clinton's in Haiti and Kosovo; Clinton's and the world's failure to act in Rwanda; and even President George W. Bush's action in Liberia.

But noble intent doesn't trump the just-war criteria that says any such action must have a reasonable chance of success.

Josh also takes issue with condition B — arguing that any action directed against the camp at Khurmal would have been tantamount to "bombing children." Here he seems to have access to intelligence that Sen. Biden and I had not seen (and intel in the no-fly zones, particularly in the Kurdish north, was far better than that coming out of Saddam-controlled central Iraq). There was no evidence that this training camp was a family-friendly workplace equipped with a child-care center. Intelligence suggested that — like our own Parris Island or The Farm — this camp was virtually entirely composed of combatant soldiers.

But let's assume Josh's objection is true for the sake of argument. Josh's argument parallels Randal's objections, in Clerks, to the destruction of the Death Star in Return of the Jedi. The still-under-construction battle station probably housed plumbers, electricians and other contractors.

"All those innocent contractors hired to do a job were killed — casualties of a war they had nothing to do with," Randal says.

You're not allowed to kill civilians, but Luke Skywalker & Co. did just that when they destroyed the second Death Star.

So we come to the principle of double-effect. It's a notoriously dodgy notion — dealing as it does with the tricky matter of intent. Double-effect is often stretched beyond its elasticity and used to cover a multitude of sins. It involves an uncomfortably murky calculus. It is also inescapable.

The Star Wars rebels present a useful illustration. If, as Randal surmises, they did kill dozens of independent contractors in the destruction of the second Death Star, those deaths were not the intended effect of their actions. Their target was the Imperial battleship itself — the destruction of which was justifiable not only as an act of self-defense, but in defense of human (er, sentient being) rights that transcended national and galactic boundaries. Their action also was conducted in a manner that minimized civilian/noncombatant casualties.

That notion — minimizing noncombatant casualties — is a key to any appeal to double effect. Consider the difference between the so-called "collateral damage" of the rebel's destruction of the second Death Star and the collateral damage of the Empire's destruction of the entire planet of Alderaan in order to take out a single rebel base there. The latter cannot be defended by an appeal to double effect.

In the very real world, if there had turned out to be hundreds of innocent children at the Khurmal camp, then indiscriminate airstrikes would have to have been taken off the table. But airstrikes were not the only option for action against that camp.

My original point, however, remains unaddressed. Which is better? Military action against an isolated camp consisting almost entirely of combatants? Or indiscriminate airstrikes against a densely populated civilian center?

Finally, we come to Josh's objection to condition C. It's not really so much an objection as a rejection.

From his "transcendent" position, national borders seem to be a fiction that exists only to propagate the racist notion that some people's lives are more valuable than others.

America's failure during the Cold War to intervene in the former Soviet Union — to invade and liberate the oppressed in Stalin's gulags — is but one illustration of this nationalistic chauvinism. It's no use countering that America was involved in a vigilant effort to contain and undermine that oppressive regime, and that this persistence succeeded in the long run. That long-run success provides little comfort to the oppressed who suffered and died for decades under the Soviet boot heel. The embrace of this overly patient, long-term strategy just shows again that we Americans do not value the lives of Russians and Ukranians as much as we value our own.

The most recent expression of what Josh sees as this racist, America-first chauvinism was, of course, the opposition to the invasion of Iraq. There were people suffering under a cruel tyrant. America possessed the military might to overthrow that tyrant and liberate those people and the only thing stopping America from acting — in Josh's view — was this illusion that "borders" mean something other than a preservation of the status quo. This makes Josh angry, so angry that he has trouble making sense or reading or hearing anything without interpreting it through the haze of that anger.

That anger is, I think, where I finally lost him. It dictates that any response I might offer, any argument I might present, any principles I might appeal to are all — by definition — racist rationales for defending the idea that American lives are the only ones that count.

All lives count, but borders do matter. It matters, for instance, that the camp at Khurmal was located within the northern no-fly zone. This area had been under U.S. protection for more than a decade with the full support and authority of the United Nations. The no-fly zones had been subject to nearly weekly bombing raids by American and British pilots for years.

An attack on a terrorist camp there is in no way comparable to a hypothetical Israeli attack on Baghdad. (If one wants an analogy involving Israel one needs look no farther than the frequent Israeli strikes on suspected militant facilities within the West Bank and Gaza. The analogy would still be inexact, but a lot closer than Josh's off-the-wall comparison.)

Josh asks if it would have been just "if the Israeli's [sic] took out Saddam on their own." Colossal foolishness is never justified. Consider the fallout from such an attack; the likelihood of regional war, the wildfire of global instability, violence, chaos, death on a massive scale.

Consequences, like borders, are real things that must be dealt with. And consequences matter even more than borders. The calamitous consequences of such an Israeli strike would have been entirely predictable.

But Josh seems to view Iraq as existing in a vacuum. Undistracted by any consideration of likely consequences and the rest of the world, he brings a distilled clarity. Saddam is evil. The worst evil. America must overthrow Saddam or be complicit in the status quo of the worst evil. Anyone who says otherwise is a defender of the worst evil.

A typical response — not so much a rebuttal as an attempt to highlight this view's dissonance — is to ask why Iraq and not, say, North Korea, or Burma, or Uzbekistan? But Josh has this response covered. If you go to his Web site, you'll find a list of oppressive nations which he invites you to help him prioritize for overthrow. (He prefers that their overthrow by done nonviolently, but he enthusiastically endorses American military intervention — and anyone who questions the latter in all cases is, you know, a racist defender of the status quo, yada yada.)

Josh imagines that if Israel "took out Saddam on their own," there would have been no other consequences, no other result or meaning or ramifications, than the felicitous removal of a tyrant.

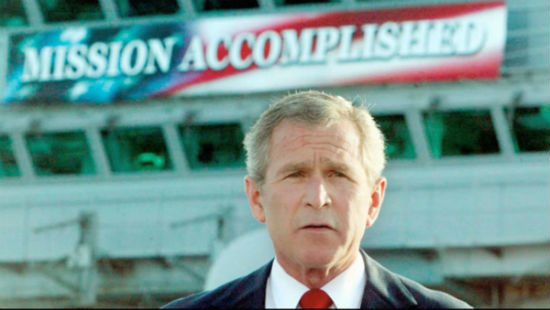

Thus, like President Bush, he imagines that is how the current scenario is playing out as well. The Iraqi people have been liberated. Saddam is in jail. The world is therefore safer and the people of Iraq better off than they have ever been before.

Anyone who wants to argue that things might have been done differently to avoid the nasty and predictable consequences we now face is shouted down with the accusation that they think the world would be better with Saddam still in power. The idea behind this accusation is that there existed only two alternatives — the military invasion, or "doing nothing."

I would point out that the people of the Czech Republic have been liberated from tyranny as well. This happened without an invasion, without an American occupation. No, it didn't happen overnight, but it happened. And the decades-long struggle that helped to bring this about ought not to be dismissed as "doing nothing" or "defending the status quo" or being "objectively pro-Soviet." And where would you rather live — Prague? Or Baghdad?

So I don't think I will be able to defend condition C to my angry friend, or to others who reject all national borders as artificial boundaries of moral obligation and all discussion of consequences as do-nothingism.

But for everyone else, here again were the facts of Khurmal:

A. It was a legitimate military target — an established threat — in an already declared, justifiable war that was being waged with international approval and cooperation.

B. It was a military target isolated from nearly all entanglements with the non-combatant civilian populations.

C. It was a military target located in a region placed by the United Nations under American military jurisdiction.

So was there any reason for it to remain undisturbed for nearly two months, other than the cynical explanation suggested by an intelligence official? — "If you take it out, you can't use it as justification for [a new, unrelated] war."