Welcome readers! Please subscribe through the buttons on the right if you enjoy this post.

In both Matthew’s and Luke’s gospels we read these words:

“And whoever does not carry their cross and follow me cannot be my disciple.” (Luke 14:27, cf. Matthew 10:38)

A couple of years ago now, I was invited to speak at a conference on nonviolence and the atonement. I chose to speak on violent forms of nonviolence: how atonement theories that treat the violent death of Jesus as salvific don’t bear nonviolent fruit toward the survivors of violence. I called on the participants to consider how penal substitution has produced violence, and to weigh the violence also that has come from more “nonviolent” theories such as moral influence and Christus Victor.

The above passage is related to all of this. “Taking up one’s cross” has been used over and over to prioritize oppressors over survivors and to encourage the oppressed to passively and patiently endure. These ways of interpreting this passage (and ones like it) have proven very convenient for oppressors and those who don’t want to disrupt the power imbalance of the status quo.

For example, when one intimate partner suffers physical or emotional abuse at the hands of another how many times have Christian pastors counseled the abused partner (usually a woman) to “bear their cross,” be “like Jesus,” and simply “turn the other cheek”? Turning the other cheek was for Jesus a call to creative, nonviolent forms of disruption, protest, and resistance. It gave those pushed to the undersides and edges of society a way to reclaim and affirm themselves despite being dehumanized. Here, I want to suggest, alongside feminist and womanist scholars, that “taking up one’s cross” is not a call to patiently, passively endure, but to take hold of life and stand up against injustice even if there is a cost for doing so. This passage is not a call to passively suffer but to protest even if the status quo threatens you for doing so.

There is a subtle difference, but the implications are huge. What we are discussing this week is called the myth of redemptive suffering. Joanne Carlson Brown and Rebecca Parker state in their essay God So Loved The World?:

“It is not acceptance of suffering that gives life; it is commitment to life that gives life. The question, moreover, is not, Am I willing to suffer? but Do I desire fully to live? This distinction is subtle and, to some, specious, but in the end it makes a great difference in how people interpret and respond to suffering. If you believe that acceptance of suffering gives life, then your resources for confronting perpetrators of violence and abuse will be numbed.” (Christianity, Patriarchy, and Abuse, pp. 1-30)

What was Jesus talking about, then, when he said: “take up your own cross?”

First, Borg and Crossan’s correctly remind us that Jesus’ cross in the gospels was about participation, not substitution:

“For Mark, it is about participation with Jesus and not substitution by Jesus. Mark has those followers recognize enough of that challenge that they change the subject and avoid the issue every time. (Marcus J. Borg and John Dominic Crossan. The Last Week: What the Gospels Really Teach About Jesus’s Final Days in Jerusalem (Kindle Locations 1589-1593)

While I agree with Borg and Crossan’s about participation rather than substitution, I disagree with their interpretation that a cross (suffering) was an intrinsic part of following Jesus. I do not subscribe to the idea that suffering is an intrinsic precursor of triumph or success. Suffering only enters into the picture of following Jesus if those benefitting from the status quo feel threatened by the changes that Jesus’ new social vision would make and threaten Jesus’ followers with a cross.

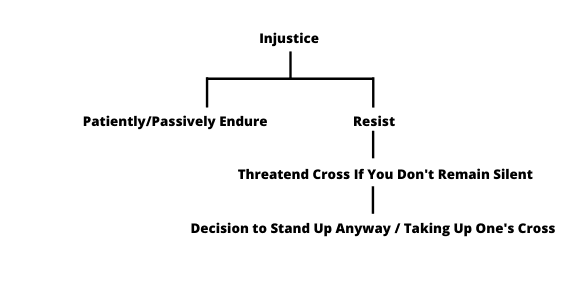

In other words, being willing to take up one’s cross is not the call to be passive in the face of suffering, but to protest and resist even in the face of being threatened with a cross (if such threats are made).

Jesus could have very well said, “Anyone who is not willing to protest and resist, even in the face of a threatened cross, is not worthy of me.” “The cross” in this context does not mean remaining passive. It means being willing to endure the results of disrupting, confronting, resisting, and protesting injustice. The cross is not a symbol of passivity but of the consequences of resistance: it is a symbol of the suffering that those in power threaten protestors with to scare them into remaining passive. Remember, the question is not how much am I willing to suffer, but how badly do I want to live!

If those in power threaten you with a cross for standing up or speaking out, then it becomes necessary for you to take up a cross and to continue to stand up against injustice. Otherwise, the cross never comes into the pictures. Protesting, for instance, does not always involve being arrested, but if it does, protest anyway! The goal in scenarios like these is not to suffer, but to refuse to let go of life. Again, the question is not are you willing to suffer, but do you desire to fully live?

How one interprets taking up one’s cross has deep implications for survivors of relational violence, as well as for all who are engaging in any form of social justice work. When those who feel threatened try to intimidate and silence your voice through fear of an imposed “cross,” the above passage calls us to count the cost and then refuse to let go of life. Do not be silenced. Reject the death of being silent.

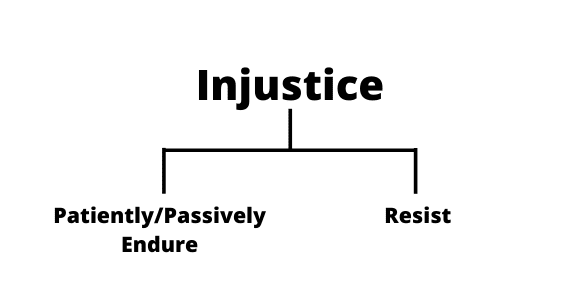

For clarity, consider the following diagram on our response to injustice:

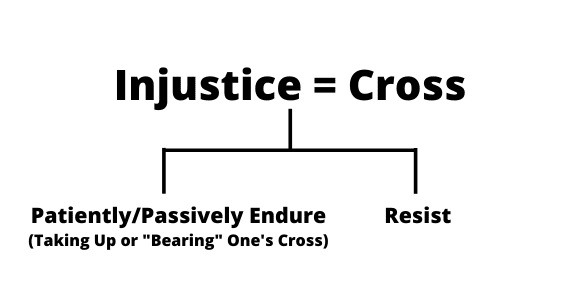

Too often, Jesus’ teaching of taking up the cross has been interpreted so that the injustice itself is the cross.

Instead, consider that the injustice is not the cross but simply an initial injustice. In this model, the cross is the threats one receives for standing up to or resisting injustice.

This interpretation of taking up one’s cross is that Jesus is not encouraging his followers to remain passive but to resist. And if a cross comes into the picture, then resist anyway. Jesus’ nonviolence was rooted in resistance, and sometimes change happens before there is a cross. So bearing a cross is not intrinsic to following Jesus. It only enters the picture when those who are threatened choose to add it.

Jesus was proposing a new social vision, a way of doing life as a community, that threatened those most benefited by systems of domination and exploitation. The way of Jesus was rooted in resource-sharing, wealth redistribution, and bringing those on the edges of society into a shared table where their voices could be heard and valued too. Did the early Jesus movement threaten those in positions of power and privilege? You bet. Jesus, here, seems to be saying, when those in power choose to threaten crosses for those standing up to systemic injustice, don’t let go. Keep holding on to hope even in the face of impossible odds. Keep holding on to life—resist.