Here are a few reasons why I am convinced that White Christians should be standing with and working alongside movements for Black lives right now.

1. Jesus was Liberator of the Oppressed

Out of all the ways that the author of the Gospel of Luke could have chosen to sum up Jesus’ gospel and life work, Luke’s gospel begins by characterizing Jesus as Liberator, Advocate, Abolitionist, and Activist:

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the prisoners, and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free.” (Luke 4:18, emphasis added.)

In the gospel stories, the central figure of the Christian faith chooses to stand in his deeply Jewish, oppression-confronting, prophetic, justice heritage:

“Speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves, for the rights of all who are destitute. Speak up and judge fairly; defend the rights of the poor and needy.” (Proverbs 31:8-9)

“God judges in favor of the oppressed.” (Psalms 146:6-7)

“Is not this the fast that I choose: to loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke?” (Isaiah 58:6)

“How terrible it will be for those who make unfair laws, and those who write laws that make life hard for people.” (Isaiah 10:1)

“Learn to do good; seek justice, rescue the oppressed.” (Isaiah 1:17)

“I hate, I despise your festivals, and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies. Even though you offer me your burnt offerings and grain offerings, I will not accept them; and the offerings of well-being of your fatted animals I will not look upon. Take away from me the noise of your songs; I will not listen to the melody of your harps. But let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.” (Amos 5:21-24)

Each of the prophets made the privileged class of their time uncomfortable by calling for systemic change. Each stood in solidarity with the oppressed in their communities.

In his book God of the Oppressed, Dr. James H. Cone wrote, “Any view of the gospel that fails to understand the Church as that community whose work and consciousness are defined by the community of the oppressed is not Christian and is thus heretical” (p. 35).

This has grave implications presently for all White, American Jesus followers.

2. Jesus’ Gospel Confronted Both Private and Systemic Sin

One of the deepest disconnects for many of my White friends is that they see these events of police officers killing Black people as isolated and individual occurrences. They don’t connect the dots and want to debate the intricacies of each case without stepping back and looking at the big picture.

But if we stop to listen first, we will discover that these cases are not disconnected or about a few bad apples, but rather one example after another of an entire systemic problem. They are daily experiences for all too many Black people.

Jesus challenged both systemic sin/injustice and personal or private, individual sins. Gustavo Gutierrez, in his landmark book A Theology of Liberation, contrasts individual sins with the social sin that the gospels challenge:

“But in the liberation approach, sin is not considered as an individual, private, or merely interior reality—asserted just enough to necessitate ‘spiritual’ redemption which does not challenge the order in which we live. Sin is regarded as a social, historical fact, the absence of fellowship and love in relationships among persons, the breach of friendship with God and with other persons, and, therefore, an interior, personal fracture. When it is considered in this way, the collective dimensions of sin are rediscovered . . . Nor is this a matter of escape into a fleshless spiritualism. Sin is evident in oppressive structures, in the exploitation of man by man, in the domination and slavery of peoples, races and social classes.” (Gustavo Gutierrez, A Theology of Liberation: 15th Anniversary Edition, pp. 102-103)

When we focus on liberating individuals from personal sin but ignore systemic sin, we create a reality that is deeply problematic. An old example I first heard from the late Howard Zinn is helpful. Imagine systemic injustice in society as an automated locomotive train racing down the tracks. We are all on this train together. We as individuals may not participate personally in the operation of the train, yet we are still on the train with everyone else as it moves along.

Similarly, someone can choose privately or personally to be a Jesus follower, but that person is still part of a much larger society that is racing down a track. Just because an individual is not racist, that doesn’t change the course of their society’s train. As a White Christian in society, I may be completely unaware of how society is structured for communities I have no contact or association with. And whether I know or not, the train we are on is still moving us all together down the tracks. White Christians are not only called to be free from racism themselves as individuals, but we are also called to be anti-racist, standing and working in solidarity with people who are targeted by racist social systems or working to dismantle those systems.

Some will ask, “If we just focus just on healing hearts, won’t we heal the systems as well?” It’s a beautiful thought. It’s simply not automatic. Social justice has never taken place from the inside-out or the top down. It happens from the margins inward, from the bottom up. Also, if one is privately a follower of Jesus, one should also be publicly involved in ending systems of oppression and privilege. It’s not enough to not be racist ourselves. We must also stand intentionally against racial inequality. The current train is racing down the tracks and it’s not enough to remain neutral or individually focused. It’s not enough to make people on the train non-racist personally or privately. The whole social train must be stopped.

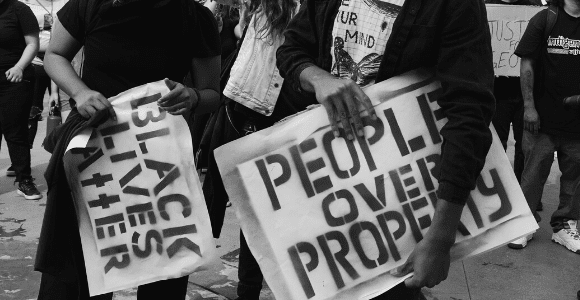

3. Jesus Valued Human Lives Over Privileged Property

Where do we see Jesus confronting systems of injustice in the gospels? All throughout the gospels! But the most infamous incident for the early Jesus community was Jesus’ protest in the courtyard of the Jerusalem Temple. Jerusalem was the heart of the Temple-State. Remember that in Jesus’ society there was no such thing as a separation of civil and religious, or church and state. The temple was not solely a religious symbol as Christians think of a church today. Yes, there were religious activities taking place there, but it was also a political symbol, much like the symbol of a state capital building, today. Jesus’ demonstration in the temple wasn’t a challenge to the religion of Judaism; Jesus was a Jew. Rather he was staging an economic protest against the systemic injustice of the Temple-State’s exploitation of the poor:

“They devour widows’ houses and for a show make lengthy prayers. These men will be punished most severely . . . But a poor widow came and put in two very small copper coins, worth only a few cents. Calling his disciples to him, Jesus said, ‘Truly I tell you, this poor widow has put more into the treasury than all the others.’” (Mark 12:40,42-34)

Mark’s gospel includes a story detail that is often overlooked.

“Then he entered Jerusalem and went into the temple; and when he had looked around at everything, as it was already late, he went out to Bethany with the twelve.” (Mark 11:11, emphasis added.)

When Jesus arrived at the Temple at the climax of what Christians refer to today as Palm Sunday, it was already too late in the day for his Temple protest to accomplish his desired result. So he went back to Bethany with his disciples, spent the night, and then came back the next day when there would be enough people to make shutting down the Temple services an effective demonstration.

Mark’s gospel adds that as a result of Jesus’ demonstration and the growing number of followers among the people, those in positions of power and privilege began “looking for a way to put Jesus to death” (Mark 11:18). A gospel that is only about saving individuals from personal sins would not evoke this kind of response from those in charge.

Luke’s gospel story reads that within days “temple police” came at night with swords and clubs to “arrest” Jesus. They came at night to avoid a riot by the people: a gospel example of police brutality against a protestor and an attempted cover-up. John’s gospel has Jesus subjected to even more temple police brutality over the day that follows his arrest.

We must not sanitize Jesus’ protest in the Temple courtyard: that day also involved property damage. When a system values property over human lives, it makes sense for some to feel the only way to move a system to listen is to impact whatever those benefiting from the system value most. Our present pandemic has proven time and again how much our present system values property, production, and profit over human life.

White Christians who claim that they would have been on Jesus’ side in the story two millennia ago, need to reassess the verity of their claim today when they find themselves speaking out more loudly against property damage than against the police’s murder of yet another Black person. A riot is “the language of the unheard,” a demand for their lives to “matter” in a system, to be valued in a system, to be respected in a system.

If you want peace, don’t simply call for peace. Add your voice to the voices that are calling for justice.

“Until the white body writhes with red rage, until the white heart heaves with black tremors, until the white head bows before yellow dreams and tan schemes and olive screams for a different world, any communion claimed will be contrivance of denial. A theologian—speaking of resurrection, in a body not bearing the scars of their own ‘crucifixion’? Impossible!” (James Perkinson, White Theology, p. 216)

Lastly, my Black friends will be the first to tell you that there is nothing wrong with seeing their color, race, or culture. These things are part of who they are, as my color, race, and culture are part of who I am. There is nothing wrong with them, and no reason we shouldn’t see their skin color along with the colors of their eyes or hair. We are not all the same, and we are all of equal worth. The human family is richly diverse and this diversity is not the problem. The problem is when we have a system that treats people as “less than” because they are Black.

So this week, with angry tears in my eyes, I lift up my own voice to the chorus raging around me:

Black.

Lives.

Matter.