Welcome readers! Please subscribe through the buttons at the right if you enjoy this post.

What happens when we have to choose between saving life and abiding by the law? In Mark, we read of Jesus asking a similar question,

“Then Jesus asked them, ‘Which is lawful on the Sabbath: to do good or to do evil, to save life or to kill?’ But they remained silent.” (Mark 3:4)

In this story in Mark’s gospel, Jesus contrasts that which is lawful and that which is life-saving, and calls our values and priorities into question. Among the values and principles we hold dear and seek to live out in our daily lives, which values hold our highest priority? Let’s look at the story in its entirety:

“Another time Jesus went into the synagogue, and a man with a shriveled hand was there. Some of them were looking for a reason to accuse Jesus, so they watched him closely to see if he would heal him on the Sabbath. Jesus said to the man with the shriveled hand, ‘Stand up in front of everyone.’ Then Jesus asked them, “Which is lawful on the Sabbath: to do good or to do evil, to save life or to kill?’ But they remained silent. He looked around at them in anger and, deeply distressed at their stubborn hearts, said to the man, ‘Stretch out your hand.’ He stretched it out, and his hand was completely restored. Then the Pharisees went out and began to plot with the Herodians how they might kill Jesus.” (Mark 3:1-6)

Each of the gospels interprets the Sabbath work-prohibition and includes acts of healing in the category of labor that was forbidden during Sabbath.

“He said to them, ‘If any of you has a sheep and it falls into a pit on the Sabbath, will you not take hold of it and lift it out?” (Matthew 12:11-12)

“Indignant because Jesus had healed on the Sabbath, the synagogue leader said to the people, ‘There are six days for work. So come and be healed on those days, not on the Sabbath.’” (Luke 13:14)

“Now the day on which Jesus had made the mud and opened the man’s eyes was a Sabbath . . . Some of the Pharisees said, ‘This man is not from God, for he does not keep the Sabbath.’” (John 9:14-16)

This interpretation of what it meant to be faithful to the Sabbath prohibitions was an interpretation by those who did not need healing, those in power and positions of privilege. It was an interpretation by those most prone to underestimate the damage of their interpretation because it did not affect them negatively.

We must also remember, as we read these stories in our context today, that people in the 1st Century didn’t look at healings the same way most people do today. Healing wasn’t considered exceptional as it is in our post-enlightenment scientific age. Healing was normative.

The point of these stories was not that Jesus healed, but about who was being healed and when. Jesus continually healed and restored those who were being socially marginalized. He stood with those being pushed to the edges of his society by the elite.

Every story of healing in the gospels questions the legitimacy of the status quo, and subverts the myths on which the status quo was based. These are stories of resistance, survival, and liberation as well as stories of healing.

Ched Myers in his book “Say to This Mountain”: Mark’s Story of Discipleship correctly states:

“In contrast to Hellenistic literature, in which miracle-workers normally function to maintain the status quo, gospel healings challenge the ordering of power. Because Jesus seeks the root causes of why people are marginalized, there is no case of healing and exorcism in Mark that does not also raise a larger question of social oppression.” (“Say to This Mountain”: Mark’s Story of Discipleship, p. 14)

Law and Order

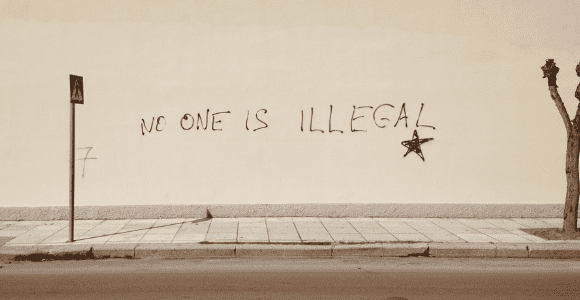

And this brings us to the point of the passage we are considering this week. What happens when we have to choose between saving life and abiding by the law? Jesus’ healings call us to take a side either with the marginalized and liberator (with Jesus) or to interpret his acts as lawless defiance. How we choose is determined by which value we hold most dear—standing alongside the vulnerable over and against harm being done or being committed to the status quo above all else.

This is nothing new. White clergy in the South used the legality argument to try to silence Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference during the Civil Rights movement. King responded,

“We should never forget that everything Adolf Hitler did in Germany was “legal” and everything the Hungarian freedom fighters did in Hungary was “illegal.” It was “illegal” to aid and comfort a Jew in Hitler’s Germany. Even so, I am sure that, had I lived in Germany at the time, I would have aided and comforted my Jewish brothers.” (Read Letter from a Birmingham Jail)

Today we can still feel the tension between what is legal and what is compassionate, just, or right. Consider the example of Scott Warren and others volunteering for the humanitarian aid organization No More Deaths. No More Deaths provides food and water along migrant trails in Arizona. Right now, Warren is on trial for offering humanitarian aid to migrants in some of the most lethal terrains of their migration. Humanitarian aid is deemed a crime, legally, but the No More Deaths organization is arguing back “that humanitarian aid is never a crime” (see CNN). NPR also reported on these actions last week: “Extending ‘Zero Tolerance’ To People Who Help Migrants Along The Border.” I can hear the echo of Jesus’ question, “Is it lawful to do good or to do evil, to save life or to kill?”

Faith Communities and Noncompliance

Within faith communities, there are also times when people have to choose between complying with what their institution’s policies allow versus doing what is right. I think of many leaders in the faith tradition I grew up in having to face compliance committees set up to enforce policies prohibiting the ordination of women, excluding LGBTQ members, and silencing scholars who hold scientific views about Earth’s geological record.

In the United Methodist tradition, there are leaders standing against policy, or what is legal, to do what is right. Just last week I read how two US conferences are ordaining and commissioning LGBTQ clergy despite their institution’s ban. (Read the entire story at https://www.umnews.org/en/news/two-us-conferences-ordain-commission-lgbtq-clergy.)

Taking both their noncompliance and their commitment to doing what is right very seriously, Bishop Sally Dyck, resident bishop of the Chicago Area, stated, “My prayer is that the church will grow in grace so as to fully give its blessing to every child of God who is called to ministry.”

Those being ordained and commissioned are experiencing firsthand the tension between standing for what one believes is right over and against the legality of continued institutional evils. The Revs. Elizabeth Evans who was commissioned as a provisional deacon rightly stated that she doesn’t believe the church can “transform the world” while upholding the same unjust structures as the world does.

It is difficult to make these types of choices. I know this firsthand, too.

In the gospels, Jesus sided with the vulnerable and marginalized over and against the institutions of his day when they practiced injustice.

He disregarded legality in favor of doing what was right until it escalated to a Roman cross—the punishment for “violating the rule of Roman law and order.” (See Kelly Brown Douglass, Stand Your Ground Black Bodies and the Justice of God, p. 171)

Jesus’ noncompliance in the gospels challenges us with this question:

Which side of the story would our actions have placed us on?

“Then Jesus asked them, ‘Which is lawful . . . to do good or to do evil, to save life or to kill?’ But they remained silent.” (Mark 3:4)