[continued from here]

As Matthew Wickman, Director of the BYU Humanities Center, pointed out, the great Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor is an in important source for a complex view of secularism that might assuage the fears of simpler folk like me.

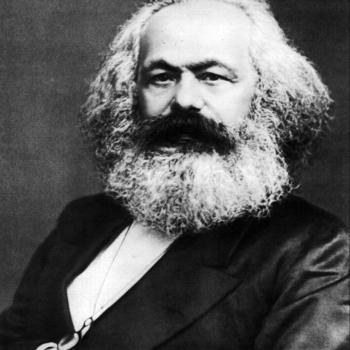

Now, it turns out that, in one of my rare breaks from going through Mormon Doctrine alphabetically and pondering the authoritative quotations mustered in The 5000-Year Leap, I actually read some books by Charles Taylor. What’s more, I actually wrote about one of them. Here is an excerpt from my ever-so-respectful but critical (is that wrong?) reading of Charles Taylor’s sprawling A Secular Age in my Responsibility of Reason:

It is not immediately clear, however, just how Taylor’s more subtle and deeper definition of “secular” differs from the straightforward, classically liberal banishment of religion from the “public” sphere to the “private.” Taylor’s sense of the problematic, questionable character of religion seems very closely related, at least, to the liberal strategy of privatization. It seems that Taylor is determined to see the condition of religion in our secular age in terms of a complex evolution of religious or “spiritual” sensibilities and not as grounded in some quite deliberate and plain political strategy. For as soon as we consider the configuration of “public” and “private” realms as a political settlement, we cannot help but notice that it is the public realm that is held to be rational and authoritative.

By focusing on the “pre-ontology” or “conditions” of belief, Taylor from the outset downplays the cognitive dimension of religion. He is interested in “different kinds of lived experience involved in understanding your life in one way or the other,” not in belief and unbelief as “rival theories” of existence or of morality. Thus he does not see religious belief as something subject to “refutation” by scientific theories such as Darwinism.

It appears that Taylor is ready to accept the privatization of religion (and thus its status as “one option among many”), but that he refuses the other half of the classical liberal equation, that is, the authority of “reason” in the public sphere.

Taylor may find it convenient to ignore the problem of the authority of secular “reason” in the public square, I argue, but this does not make the problem go away. And in fact, Taylor can be observed deferring to this authority (as articulated in the work of the political philosopher John Rawls, for example). …

In the last analysis, Taylor in fact concedes the decisive point to the liberationists or democratic expressivists, namely, the claim that individual meaning can be severed from authoritative public norms: “the ‘sacred’, either religious or ‘laique,’ has become uncoupled from our political allegiance.”[i] In all previous understandings of political life, as Taylor has largely devoted his career to showing, the bonds of political authority were in some way grounded in some sacred norms, “strong evaluations,” or ideas of the good prior to individual preferences; but here Taylor appears convinced that this linkage has been broken or dissolved, making possible a society in which “the spiritual as such is no longer intrinsically related to society,”[ii] a society therefore of “unlimited” pluralism.

This is truly puzzling, and seems to be explicable only in terms of rather narrowly political considerations. For has not Taylor himself supplied the strongest grounds for doubting the possibility of such an uncoupling? Without drawing upon the powerful arguments of Sources of the Self for the inevitability of “strong evaluations” in political judgments, let us simply recall the anthropological axioms that we found in the introduction to the present volume. Taylor has shown that every human life takes place within some (surely dynamic or evolving) conception or pre-theoretical sense of a possible “fullness” of existence…

[and a little further on…] Taylor thus provides powerful evidence and reasoning against his own argument for the inauguration of a new age in which the problem of human “fullness” could become irrelevant to politics, or in which the extraordinary could become so ordinary that there would be no possibility of appealing beyond given political norms. His belief that “naïve” belief has become obsolete ignores the replacement of traditional belief (which has indeed been rendered problematic for most people today) by an increasingly axiomatic or “naïve” counter-ethic of liberation and the corresponding and dreadfully naïve abandonment of truth to purely instrumental “reason.”

This, then, is the question: is secularism so messy and complicated that it can’t possibly be a moral and political problem, but only a matter of subtle interpretation by academics far above the moral and political fray? Or does secularism have a moral and political edge that actually matters for non-academics and that, moreover, shapes the academic discussion whether academics like to own up to it or not?

For those paying attention to moral and political developments, I would submit that this question all but answers itself. If you are so far above this practical fray as to not know what I might be talking about, I invite you to consider the very astute, learned, and moderate reflections of Steven D. Smith of U. of San Diego Law School (as sampled in my earlier post). Or you might consider the worries stated by an honest, earnest and learned liberal, Damon Linker:

Only in the modern West and only within the past few decades has the concern for care/harm — with both care and harm defined exclusively in terms of individual preferences and desires — begun to drive out other moral principles. That’s what I mean when I write about moral libertarianism and the elevation of individual consent into the sole justifiable measure of right and wrong. Outside of the relatively narrow sphere of the law, this shift isn’t taking the form of a slide down a slippery slope, as if the acceptance of homosexuality were causing or leading to the acceptance of other sexual behaviors that were once considered deviant. Rather, the public condemnation of all such behaviors is slowly fading away because of an underlying ethical shift that has transformed care/harm into the ultimate moral trump card.

That’s why the recent 6,200-word New York magazine interview with a committed “zoophile” is so important — because it’s such a perfect example of this transformation and its practical implications. …

Don’t get me wrong: being nice is definitely a good thing. But is it the best thing? The highest thing? The thing that should override every other possible moral judgment? I’m not so sure — and if I’m right in my suspicions, many liberals harbor similar doubts, while also preferring not to be made to confront the inevitable moral trade-offs. My columns on these topics are designed to force them to do exactly that — to bring them around to recognizing the questionableness and possible social and cultural costs of treating niceness as the ultimate — and perhaps the only — moral good.

No wonder so many liberals find me irritating.

None of us knows the social and cultural consequences of expunging all notions of sanctity/degradation from our public life — because it’s never been tried before. I think that very fact makes it worthy of serious reflection, wonder, and even worry.

Thus wrote my former ex-friend, the liberal Damon Linker. If Damon remains a liberal, it’s because, despite his worries, he is not willing, apparently, to bet against this expunging of all non-liberal morality. And I suppose there’s no way to prove that an experiment that has never been tried before in human history is not a good idea. (If I deserve the epithet “conservative,” it is simply because I am willing to take counsel from the doubts I share with Linker about the wisdom of this great experiment.) But whatever bet you place on this secular experiment, it seems hard to deny that it amounts to more than a claim of nice people to have a place at the table and not be dominated by others. It is an experiment that is changing our world, and our universities are a big part of this experiment.

Profs. Miller and Wickman, and all those unfearful academics who are at home in the secular academy: I invite you to explain why you think this experiment is OK, or tell me (privately, if you like, so you won’t be marginalized as a “conservative”) that you wonder, with me and Linker, whether it might be a big problem. But don’t just tell me it’s all messy and complicated, drive on, there’s nothing to see here.

I think there is such a thing as secularism, and I think that just about anyone not thoroughly immured in the delights of academic complexity can see it. Hence my simplicity.

……..

Just as I was bringing this treatise to a conclusion, I happened to listen to Brother Lloyd Newell’s devotional address at BYU this morning. It’s a really good speech. Just after the 32 minute mark, he asks, “what does it mean to have a sound mind?” “You and I and the rest of the world are in the midst of an intellectual storm, a hurricane of philosophies and ideologies, with winds of doctrine tossing many of us to and fro…”

Just as I was bringing this treatise to a conclusion, I happened to listen to Brother Lloyd Newell’s devotional address at BYU this morning. It’s a really good speech. Just after the 32 minute mark, he asks, “what does it mean to have a sound mind?” “You and I and the rest of the world are in the midst of an intellectual storm, a hurricane of philosophies and ideologies, with winds of doctrine tossing many of us to and fro…”

My simplicity, eschewed by Profs. Miller and Wickman, and, apparently, the great majority or critical mass of LDS scholars and intellectuals, lies in my agreement with Brother Newell (and not with him alone, to be sure), that we are in the midst of an ideological storm To believe that such a storm exists takes no leap of faith or blind commitment to religious authority. On the contrary, scholars with eyes to see, like Steven D. Smith and Damon Linker, are very aware of it. So is Charles Taylor, it seems, but he believes it is possible to live fully in the storm, in fact to embrace the storm, without being swept away by it.

How are we to stand in the storm? Of course the most important answer, as Brother Newell teaches is: we must anchor ourselves to the rock of our Lord Jesus Christ. I only mean to add that LDS scholars and intellectuals have the responsibility to identify and explain the storm, and in fact to show that there is by no means any rational necessity in embracing it.

As I have written before, I believe we are failing to do this, not because we are too “rational,” but because we are not rational enough — we are not using our rational faculties and our learning to question the irrational “rationalism” of the “secular.”

I wonder how many classrooms and how many publications in the social sciences and humanities at BYU are devoted to identifying and countering this storm. Those who agree with Professor Wickman that, well, it’s complicated, and God must love secularism anyway, because he made so much of it, or those agree with Adam Miller that we must simply open ourselves to “mutual transformation,” are not likely to help students engage the ideological storm that Newell, Smith, Linker and I can see and hear raging about us.

So that is the question. I realize there are many dimensions of the question of the meaning of the “secular” that I have not engaged here. But I do presume to confront my colleagues with a quite simple question: is there or is there not a force clearly driving our society in a “secular” direction, in fact threatening to bring to completion the ascendancy of a view that shows no respect to any rational, moral or religious authority above “human rights,” where these rights are defined as rights to whatever individual human beings desire? If there is such a force, is there anything we intellectuals might do to identify and resist it?

Just asking.