We had a real working fireplace, at the house I grew up in. Not a gas log but a regular old-fashioned, wood-burning fireplace protected by a glass screen you could pull open if you were allowed, which we never were. We might shatter the glass by playing with it, and then we’d need stitches and a tetanus shot. I didn’t think of that fireplace as as an oddity. Everyone I read about in books had fireplaces, after all. But I’ve never lived in a house that had once since, so maybe it is.

We rarely used the fireplace. The house had gas heat as well, so there was no need. But once in awhile, my father would use the fireplace to burn cardboard boxes. We would sit around it and watch. My sister and I pretended to be pioneers or Jo and Amy from Little Women; my brothers would imagine the glass was a movie theater screen playing some violent apocalyptic thriller. Then we’d go about our business like good middle-class suburban Midwesterners, for whom fire was entertainment and not necessity. The fireplace was a purely aesthetic thing.

One day, a bird flew in the chimney and got trapped there.

Apparently there’s a flue or a damper or some technical piece of a chimney with a name I don’t know that you’re supposed to close, when you’re not having a fire in the fireplace, and that will prevent birds getting in. But we didn’t know that. We thought about the fireplace three times a year; we left the chimney open all the time. I’m surprised we didn’t get birds more often than once, but this was the only time in my memory that a bird got trapped behind the glass.

I was trying to read when I heard it– fluttering, like a thick paperback book rolling down a wooden staircase. Scratching, like the mice we got in the drywall one winter but louder and more robust. It sounded like desperation. It sounded like something that was drowning, but in air rather than water.

And then it stopped.

I went back to my book.

It started up again– fluttering, scratching, books rolling down stairs, something larger than a mouse scratching with an appendage that wasn’t a paw. Desperation and suffering.

“There’s a bird stuck in the chimney,” said my father sadly. “It’s dying. It’s sad.”

And then he left for the day.

The fluttering died down again.

I tried not to think about the bird. We weren’t supposed to open the glass. There was soot behind the glass– probably lots of it, as I’d never seen my parents clean it out in my life. We just didn’t make fires often enough to think about things like that. And this was the living room, the one room in the house my mother was adamant that we keep nice. The “family room” and the kitchen were for everyday messes; the dining room was for homeschooling, and sometimes for formal dinners. The unfinished basement was a lawless and chaotic cave where we could do as we pleased, including crayon on the walls. But the living room was a sanctuary. The living room was for company. We couldn’t get soot all over the living room.

The bird fluttered again.

I wondered why my father assumed the bird was dying. Maybe he thought it would suffocate in short order– though the fireplace couldn’t be airtight, or you couldn’t make a fire in it. Maybe these were its death throes, and soon it would quiet down.

There was no way I’d be allowed to let a live bird into the living room. It would poop, or knock something over. The mess would be unimaginable. I’d get into trouble.

The bird renewed its thrashing, worse than ever.

I have never been very good at doing things, and I was even worse when I was a child, but I had to do something fast. I covered my hand in a new kitchen trash bag, for some reason. I think I was afraid of rabies. I went to open the front door and the window; I got my sister and youngest brother.

“We’re going to save the bird,” I told them. “Don’t tell Mom and Dad.”

And then I grabbed the handles of the glass screen we weren’t supposed to touch.

And then I opened the fireplace.

I was afraid I’d find the bird lodged up in the chimney with its wing broken or caught on… something, whatever it is there is inside fireplaces and chimneys. That odd metal rib cage you use to put the logs on, which doesn’t seem to have a name, perhaps. Something like that. But I didn’t. She was free and unhurt, her drab feathers stained black with dust, looking deceptively calm as all birds do when they’re perfectly still. I think she was a swallow, but I couldn’t tell with all the ashes on her feathers. I certainly didn’t know that she was a she, but that was what I decided in my mind as I looked at her. She was a she bird who might answer to “Birdie.”

“Here, Birdie Birdie.”I reached for the bird with my bag-covered hand.

She flew at me.

As I ducked, she fluttered past me.

She flew around the room, looking something like a miniature raven in all of that soot but not nearly as ominous. For a moment, she alighted on the sill of the big picture window that didn’t open, dirtying it. Then she flew into a corner of the room, crashed into it and fell, leaving a gray smear.

My sister dove for her, but she flew off again. This time, she alighted on a bracket shelf, upsetting several valuable glass knick-knacks.

I made a swipe at her with my trash bag.

She flew away, over to the staircase; she crashed one more time before she reached the open window. There was a surreal moment where I didn’t know if the bird was in or out, and then she was certainly out. She was in the yard– in the fresh air, in the trees outside, over away where I couldn’t see her, in the blue sky, out in the world where living things live and belong and can do good.

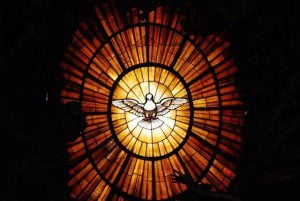

I don’t know much of anything about the spiritual life, but I do know this: the Bird is alive, and you mustn’t forbid the door to be opened. We all have a door like that– a door that leads to blackness we haven’t cleaned, in the stuffiest room of our own interior castle where we hate to have anything disrupted. It’s the most frightening thing in the world to discover that the Bird has found a way into the dark place, but you have to let the Child open the door. You mustn’t hinder the Bird from flying, even though the order you prize will be disrupted and the darkness will become apparent.

Everything good there could ever be, depends upon letting that Bird fly free. Open the glass, scatter the soot, submit to having the room disheveled.

Veni, Sancte Spiritus.

(image via Pixabay)