I’m sure by now you’ve heard that the Wyoming Valley West school district in Pennsylvania threatened parents that their children would be put in foster care if they didn’t pay up the children’s lunch money debts. Such an extreme punishment for the crime of poverty garnered national attention, and most of the reactions I’ve seen have been shock. I, myself, am shocked. As the editorial board of the Times-Tribune of Scranton pointed out, the school district has become the school bully shaking down kids for their lunch money.

I was relieved when donors came forward offering to pay off all the school lunch debt– it apparently came to $22,000 for the whole district. There must be a lot of hungry children there. So far, five different philanthropists have offered to pay off the debts for everyone. I don’t like to romanticize the notion of a donor coming forward to save thousands of children from being kidnapped from their poverty stricken parents; I think that takes the public eye off of where it belongs. We ought to be wondering how society became so horrendous that such a predicament even existed in the first place. But the villains and heroes are clear. Anyone offering to pay tens of thousands of dollars to keep poor children from losing their mothers and fathers is doing the most generous thing they can in a rotten scenario.

The school district, however, is so far refusing to accept the money. They want the poor families to pay the bill.

One of the would-be donors, Todd Carmichael, said he specifically wanted to pay the debts because he himself had been poor in elementary school, and remembered how embarrassing that was. He says that he called Joseph Mazur, the school district president, but Mazur became “combative” and hung up on him. This even though Mazur had previously stated that the district was “strapped for cash” and desperately needed that lunch money. But apparently he won’t take the lunch money from rich people who want to be helpful. He wants to shake down poor families who fell behind on lunch payments, and to traumatize their children at the expense of the state if they can’t.

I hope I can be forgiven for surmising that the cruelty is the whole point of this exercise– the cruelty is meant to teach a lesson. The purpose of a school, after all, is to teach. That’s what schools are for. This school district seems keen on teaching children a classic lesson in economics: there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch. In this case, if you eat a lunch you can’t afford to pay for, something terrible will happen to you, so you’d better be careful with money.

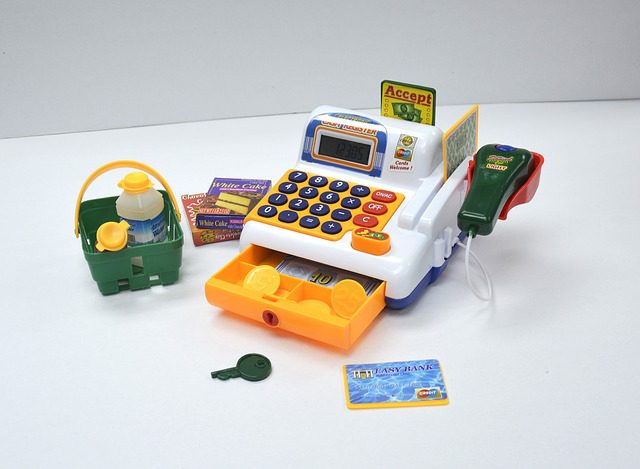

I was also taught to be careful with money in school, back before my family switched to homeschooling. Sister Mary Thomasina, God rest her soul, taught her Kindergarten class that a dollar is made of one hundred cents, a quarter of twenty-five cents, a dime of ten, a nickel of five, and a penny of one. Then she set up a plastic play McDonald’s booth, a plastic sit-down restaurant and a plastic farmer’s market. She assigned a certain amount of time when each student would get to be the McDonald’s cashier or the waiter or the person working the till at the farmer’s market, and those who weren’t working a shift got a pile of paper and plastic money from the toy bank. We bought plastic food and made plastic change all day long. Then we had a real snack, cookies and juice, and went home. No one threatened to kidnap me for eating the cookies and drinking the juice even though I didn’t pay for them. I think another mom brought them to treat the students anyway. Sister Mary Thomasina had us all chorus “thank you” to the cookie bringer after we said grace. I may not have grown up to be an entrepreneur, but I still somehow managed to learn that lunch costs money, and that a dollar is made of one hundred cents.

I would like to suggest a different pedagogy for Mr. Mazur and the Wyoming Valley West school district: the purpose of a school, as you already know, is to teach. At minimum, the purpose of a school is so that children will not grow to adulthood without learning how to read and perform basic arithmetic operations. Having enough nutritious food to eat is a necessary part of growing and developing into a healthy adult. And it’s impossible to properly learn your reading and arithmetic if you’re hungry, not to mention depressed from having watched your classmates eat a meal you couldn’t afford. So, if for no more noble reason than so that a child doesn’t fail his long division tests, a school needs to make sure that children have something to eat at lunchtime.

If children are not being abused by their parents, then the healthiest place for them to grow up is with their parents. Growing up with their loving mom and dad, even if mom and dad don’t have very much money, is part of mental health, and children suffering from poor mental health can’t grow into well-adjusted adults. They can’t even be expected to attend to their reading and arithmetic. So, if for no other reason than so that a child won’t fail her spelling tests, you shouldn’t have children taken away from their parents for the crime of poverty.

If you really don’t have the money for this because the district is strapped for cash, you should swallow your pride and work with local donors to find a way to afford school lunches for everyone, and you should do it ahead of time instead of shaking down parents with threats of kidnapping first. Maybe then you can invite the donors to a school assembly and take their picture with the student body and thank them in person. Maybe the children could paint a big poster or make a great big stack of thank-you cards for art class, to present to the donors at the school assembly. Perhaps the donors would like to give the kids a little talk on why they felt it was important to help cover the cost of lunches.

No, this would not teach children the important life lesson that there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch and everyone who can’t pay for their food ends up suffering, one way or another. I have a feeling children who are in such poverty that they regularly can’t afford meals already learned this lesson at home.

Instead, it would teach children the important life lesson that children deserve to be healthy– and that making sure that human bodies and minds are fed and kept healthy, especially when they’re young, is a priority for a civilized society. It’s much more important than making sure that humans are careful with money. Being careful with money is important, though, because if you’re careful with money, you might be able to do wonderful things like give the money you’ve saved to the local school so that poor children can have lunch. And with the guidance of good teachers, children can look to that example and be excited to grow up and have jobs that will give them the means to help other people get the things that they need to be healthy. Or better yet, they can grow up to radically change society so that children don’t have to fear not being able to afford lunches in the first place, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves. And then the teachers can get out the play cash register, the play farmer’s market, and the paper and plastic toy coins, and teach children to count their bills and make change. Because they’ve already learned the foundation of any ethical talk about money: that money is only a means to an end, and that taking care of people’s needs is what money is for.

People are more important than money. People who don’t have enough money still have value as people, and because they have value they need to be helped. There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch, which means that people who have the means are responsible to come up with ways to provide lunch. That’s how a community is supposed to work.

If children don’t grow up learning that, I’d say their education has truly failed.

(image via pixabay)