I ended up back in that hospital chapel I found during my adventure with the stray cat last month.

The bus in Steubenville comes about once every hour, and it takes a break from its usual route during the two o’clock hour so it can ferry students home from Big Red High School. If you’re stuck without a car, you shouldn’t make doctors’ appointments at two-thirty. But that was when they could see me. I was coming to the doctor from a dental appointment in a different part of town, and I ended up at Trinity West Hospital more than an hour early.

There was no convenient place to sit outdoors near the hospital.

I asked the contact tracer at the door if I was allowed to wait in the hospital chapel for an hour, and she said I could.

It’s remarkable how safe it feels, in a hospital, during a pandemic. Everyone was carefully masked and social distancing. The chairs in every waiting area were pushed far apart. Custodians were sanitizing everything every so often. I felt much more confident about spending an hour there, than an hour on any other necessary errand or even an hour in the parking lot.

The chapel at Trinity East hospital is actually comprised of three rooms. There is a small chapel set up like a Catholic church, with an altar, a pulpit and seats for Mass. There is a small, dark side chapel with an ugly crucifix and an electric flicker candle, where the Eucharist is reposed. And there is a tiny room that looks like it was originally a confessional, labeled the “Tranquility Room.” There are incense sticks, gluten-free aromatherapy play clay and bottles of essential oil on a side table next to a massage chair in the Tranquility Room, which would be very soothing if they weren’t crammed into a tiny closet along with three nearly lifesized statues of the Virgin Mary, Saint Joseph and Saint Jude. It feels like you’re in some kind of game of how-many-people-can-fit-in-a-phone-booth.

I didn’t spend much time in the Tranquility Room. It was too crowded.

I spent quite some time in the Eucharistic chapel, staring at the ugly crucifix and the tabernacle below it. The corpus on that crucifix does not look dead. It’s dreadfully alive, twisted and writhing in agony, and the light shining on it casts an even more macabre shadow, two or three tangles of suffering arms and legs instead of one.

As someone who struggles with nerve pain on and off, I can relate.

I told Christ how much I miss Him. I haven’t been away from Him, of course, nor could I ever be. He is everywhere present and filling all things. But I miss Him like this: physically present, tangible, visible. There’s always some water vapor floating in the air, after all, but breathing doesn’t quench thirst. You can still die if all you do is breathe. You need to drink liquid water once in awhile. And that’s how I feel about Christ: He is everywhere, but I want to eat and drink Him again. Thanks to the pandemic and Michael’s asthma, that will have to wait until we can get a car and go to the next diocese over, where they’re having parking lot Masses and Masses with masks mandatory and social distancing enforced. We don’t dare go anywhere crowded indoors.

My friends who are lapsed Catholics tell me that eventually you don’t miss the Eucharist anymore. I love and respect those people. But I don’t want to not miss it. I want Him back.

I told Him so.

I paced back and forth in the main chapel. Thanks to the pandemic there weren’t any missals or breviaries to read, but the big book for Mass was still at the pulpit with the markers in the right place, so I read the day’s readings.

I stared for a long time at a stained glass window portraying Saint Francis hugging a Jack-o-Lantern.

No, it wasn’t a Jack-o-Lantern. It was a head with no nose.

No, at the third glance, it wasn’t just a head. It was a human body, skinny and shrunken with disease, and a triangular black abscess where his nose ought to be. A leper, with the sickness far advanced. Saint Francis was embracing him. I love that story.

The windows behind the altar showed several scenes from the hagiography of Saint Francis. Here was Saint Francis taking his clothes off in public and the bishop covering him. Here was Saint Francis embracing a leper as ugly as that crucifix in the side chapel. Here was Saint Francis nudging a tilting church building back into place in the Pope’s dream. Here was Saint Francis talking to woodland creatures. Here he was receiving the stigmata from a winged crucifix. And here he was lying dead, surrounded by his spiritual children. I think in real life, Saint Francis died naked, but in the window he’s wearing a robe.

I stood there staring for a long time.

Saint Francis was a glorious soul, and also the most eccentric weirdo who ever lived.

When you’re raised Catholic, you’re exposed to many simplistic hagiographies of saints. These books tend to paint everything the saint did before their conversion as sin, and everything they did after their conversion as part of their sanctity– everything, no matter how ridiculous. Saint Francis’s silliest antics, Saint Catherine of Sienna drinking the dirty bathwater and starving herself, Saint Pio’s crabbiness, Saint Therese’s sensitivity, all of these were actually holiness.

When you get a little older and start to ask questions, you come to the conclusion that perhaps these weren’t all marks of sanctity. Maybe the saints had anxiety and depression or worse afflictions. Maybe they just had strange personalities. If you’re like me, you start keeping lists in your mind. “This incident was real, beautiful charity inspired by God. This one was probably a misunderstanding of something God wanted. This was a weird but harmless pious custom that was part of the saint’s culture. This was the saint actually committing a sin but the hagiographer got carried away and decided it was not a sin. This was probably a psychotic break. About this, I have no idea.”

I think, when you get a little wiser, you realized that having a list like that doesn’t really matter in the same way you thought it did. Of course, it’s important to know when something is erroneous or sinful, especially if a pious person is describing it to you in a way that makes it seem admirable. You have to be able to do that as part of forming your conscience. But you don’t have to look at every strange or silly or wonderful thing a person did, and know exactly what was sanctity and what was something else.

That kind of distinction isn’t real. There isn’t holiness over here in this part of life and ordinary messy human personalities in another. There isn’t God in the chapel and when I’m doing a good deed, but lack of God when I’m riding the bus or going to the doctor. We don’t worship a god who is off somewhere else not bothering with us. We worship Emmanuel, God-with-us. Holiness is something that’s lived out in human lives. Saints are human beings, with human bodies and minds and weaknesses, living in a certain culture in a certain time. They are people. Saints are people who tried to serve God and failed and repented and tried again, and God manifested His grace in their lives, in their cultures, in their bodies and minds and not somebody else’s. Saints are men and women. Saints are from Italy and France and the United States, from Brazil and Sudan and Nigeria, from this region of China and that city in India. Saints are part of this or that race and culture. Saints have good mental health or they have anxiety or depression, bipolar disorder, PTSD, schizophrenia, dementia. Saints are on or off the autism spectrum. Saints are introverts or extroverts. Saints are good at standing up for themselves or they’re pushovers. Saints have a good sense of humor or a bad one, lots of common sense or none at all. Saints have good and bad days. And the grace of God is manifested in all of that. All of that becomes grace.

God is present right here, in people, and in life. Even in this life, bored and annoyed, unable to receive the sacraments when I want to, trying to make sense of the city buses and get to the doctor on time.

That was what passed through my mind as I waited in the eccentric hospital chapel on an inconvenient day, staring at Saint Francis embracing a Jack-o-Lantern, when I hadn’t been to Mass in weeks.

This is what I leave you with this weekend.

The person you are, and not somebody else. The world you inhabit, and not a better world. The struggles you have, and not nicer-looking struggles. Those are where God is coming to save you. That’s where the grace and the sanctity will be found.

God-with-us, not God-somewhere-else.

That’s something to be glad about.

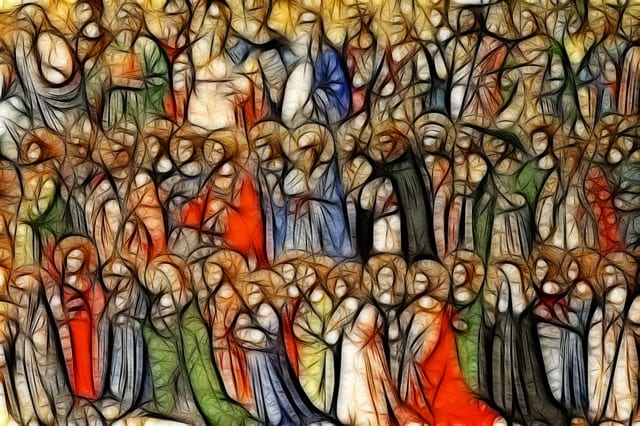

Image via Pixabay.

Mary Pezzulo is the author of Meditations on the Way of the Cross.

Steel Magnificat operates almost entirely on tips. To tip the author, visit our donate page.