After I left my old church on Friday, I drove around for a bit.

I was supposed to go back to the South Side and greet my wonderful hosts, but I felt like quiet time.

It’s a horrible thing to get shattered, and I was shattered. It’s a horrible thing when all the sights and sounds and smells you were raised to associate with God, just remind you of suffering. That gut feeling that God hated me and was going to damn me to hell for driving to Columbus to attend the Pride parade was still gnawing.

“I wish I knew what you wanted,” I prayed. “I wish I knew where you were.”

I looked at my Saint Michael icon, and told them that I was afraid God was going to smack me for coming to town to see a parade.

I drove up and down High Street.

I used to live just off of High Street, so I drove past my old house. I smiled to see that the new owners have a messy garden. They must be good people to have a garden so big and so untidy. I would like to meet them.

I looked at the odd rectangular window, in the one little room that we called “The Chapel.” The Chapel was the room in our house where we held evening devotions, sometimes singing hymns with my mother playing the tambourine. I wondered what the new owner used it for.

“I wish I knew where you were.”

When Adam sinned and hid from God, God’s first words were “Where are you?” Here I was not knowing if I was sinning, not knowing who I could even ask if I was sinning, asking “Where are you?” to God.

I drove past the wonderful library where I spent so much time as a child. I drove through Clintonville to Beechwold.

I passed the corner where a homeless person used to sit on a bench every evening. We drove past him a hundred times in the nineties, but never stopped.

I stopped in the parking lot of the Catholic school where I was bullied into full-blown PTSD, in the third and fourth grade. The one with the evil Mrs. Laurent and the boys who assaulted me. When I’d come to Columbus last September, the school was in session so I couldn’t very well go for a walk on the playground. This time it was empty, and I did. I walked around the whole yard, remembering far too much. There was the weird square church with the big black roof and the skinny steeple, like a flattened Eiffel Tower. There was the tree I used to talk to when I was lonely. There was the space where the bullies pushed me back into the corner between the gym staircase and the wall and started hurting me, tearing up the skin on my arm with their nails.

There, on the other side of the soccer field beside the baseball diamond, was the scrubby collection of bushes where beautiful Julia and I used to hide. We pretended this was our secret tree fort in the forest. We were magical shape-shifting elven beings, spiriting away foundlings from the cruel orphanage and raising them as magic-wielders in the woods. Sometimes other misfit children would play with us, taking the roles of the foundlings. Sometimes boys would come over and mock us for being so eccentric, and especially mock me because I was fat and ugly. They’d shout “what’s that SMELL?” and call me a pig.

Sometimes the yard teachers would blow their whistles and scold us for hiding in the bushes. The rule was that we had to stay out in plain sight. We weren’t allowed to try to get away from the bullies, but we also weren’t allowed to fight them. When I defended myself, I got punished and lectured and kept in at recess, and missed a chance to pretend with Julia.

I bent over to peer into our old hiding place, half expecting to see Julia there, half expecting a yard teacher would blow her whistle and make me sit in time out. But there was no one, only a trail of dark soil winding between the weeds. Other misfit children had hidden here recently, often enough to wear down the ground cover into a path.

Wherever those children are this summer, I hope that they are happy.

Wherever Julia is, I wish her every good thing there could ever be.

I went to the door of the church, and found it locked.

“Where are you?” God said to Adam.

I moved on, up past Maple Grove where my grandparents went to church, through Old Beechwold where they used to live. I said hello to more of the trees I used to talk to when I was a little girl. I was so happy they hadn’t cut down the honey locust. I came out and drove back down High Street, intending to go back to the South Side right away.

And then I saw them.

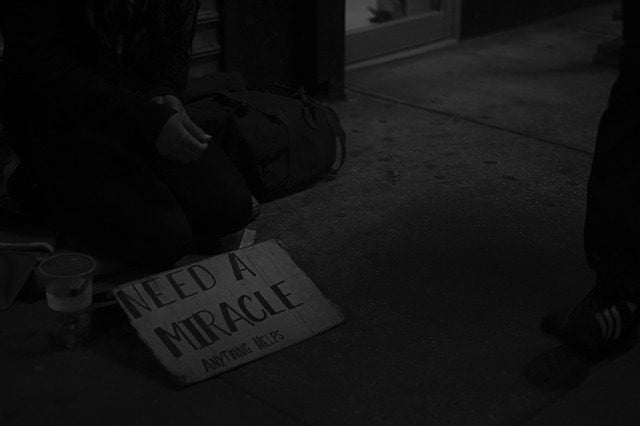

A beggar was standing with a sign, off on a side street. Not the homeless person from my childhood but a different poor person needing help. His family was with him– two tired children and a woman in a folding chair. I didn’t care if he was faking his need. I didn’t care if he was going to walk away with my money and buy drugs. I didn’t care about anything except a chance to come out of hiding and meet the living God. Next thing I knew I was stumbling out of my car, fumbling with my wallet, arms full of the water bottles that still had plenty of ice.

“Here!” I said, handing the man money, and “Here!” handing his wife the water.

He looked genuinely surprised. “Thank you very much! God bless you!”

“Thank you,” I said, and meant it. “God bless you.”

I drove back to the south side to see my friends.

And for awhile, nothing hurt.

Image via pixabay

Mary Pezzulo is the author of Meditations on the Way of the Cross, The Sorrows and Joys of Mary, and Stumbling into Grace: How We Meet God in Tiny Works of Mercy.

Steel Magnificat operates almost entirely on tips. To tip the author, visit our donate page.