From its earliest formulations, Catholic theology has attributed the traits of immutability and impassibility to God’s nature. These traits, which build on ancient Greek philosophy, form much of what can be said about the nature of God.

In this essay, I will explore what immutability and impassibility mean and why these traits have been attributed to God. Finally, I will address some of the problems that immutability and impassibility present regarding Catholic Christology and soteriology.

Because the distance between the Creator and His creation is infinite, it is, in principle, impossible to provide an essential definition of God. There are at least two reasons why this is so. First, an essential definition details the essence of that which is being defined. Since temporal creatures cannot comprehend the eternal, it is impossible for humans to understand God’s essence or nature. The second reason comes to us by way of Divine Revelation and philosophy. That is, God is infinite. Since an essential definition limits the subject (so as to make a distinction) and since that which is infinite cannot be limited (by definition), it is impossible to provide a definition of who God is in His nature.

Nevertheless, that same Divine Revelation and philosophy have provided theology with enough data to attribute specific properties to God. Among these are immutability and impassibility. While immutability and impassibility are similar, they do have significant differences. Immutability refers to the belief that an infinite God is changeless. There are several ways this can be considered.

The first way is to view change as synonymous with cause. That is, a thing is changed when it is caused by something. Whatever is changing is being changed by something else, and that thing is also being changed by another. An acorn changes into a tree, and a child changes into an adult. However, this chain cannot be infinite. Thus, there must be a thing that causes change, but itself is not changed. That is God.

A second way to understand the immutability of God is to realize that change and time cannot be separated. Since God is outside of time (indeed, He is the cause of time), it is manifest that God cannot change.

Thirdly, that which is subject to change is lacking in some perfection. If that were not so, it would not need to change. However, because God necessarily possesses every perfection of being, there is no need for change. This is in agreement with the scriptural data, as well. “For I, the Lord, do not change.” (Malachi 3:6).

Impassibility refers to the belief that God is immune from suffering. Suffering is generally categorized as being either physical or mental (emotional). Since God is a spirit and is omnipotent, He is excluded from physical suffering.

Emotional suffering entails a change in the state of the one suffering, and since God is changeless, it is said that God is impassible. “The Lord [who] is the everlasting God, the Creator of the ends of the earth. He does not faint or grow weary” (Isaiah 40:28).

A contemplation of these characteristics of God suggests some problems, however. The first issue is theological. It is the tendency to see an immutable and impassible God as distant and impersonal in contrast to the immanent and personal.

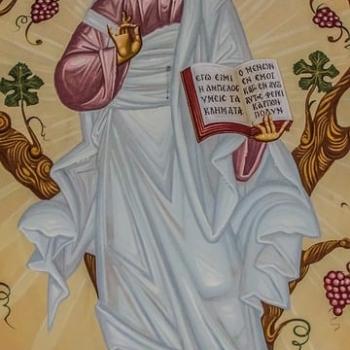

The second problem is Christological and involves the Incarnation and Crucifixion of Christ. If God cannot suffer, and Christ is God, how can Scripture teach that “Christ also suffered for sins once, the righteous for the sake of the unrighteous”? (1 Peter 3:18). Perhaps even more striking are those biblical verses that attribute emotional states to God. God is said to have taken “pity on his people” and to have “grieved in his heart.” (See Judges 2:18 and Psalm 78:40).

In addressing the first problem, one begins with what God has revealed about Himself. The data provided by the Bible suggests a God Who interacts with and cares for His creation. The God of the Bible speaks to and through His creation. “For I, the Lord, am your God, the Holy One of Israel, your savior. You are precious in my eyes and honored, and I love you.” (Isaiah 43:3-13). Finally, God “so loved the world that He gave His only begotten son.” (John 3:16).

So, despite God’s utter otherness and transcendent nature, He is not a distant, deist god but a God intimately connected to His creation.

A much more difficult problem is presented by suffering as it relates to God. How are we to understand the God Who exhibits emotions? Furthermore, if Christ, as God incarnate, cannot suffer, how can he effectuate our salvation, which requires suffering to reconcile human beings and God?

The anthropomorphic traits attributed to God should be understood analogically. As indicated above, it is, in principle, impossible for human beings to comprehend God. The problem is epistemological, and anthropomorphisms allow us to comprehend the incomprehensible at least partially.

Ultimately, language fails us, and the best we can do is state that God is God, and we are not. Our human expressions are intrinsically inadequate in explaining who God is fully and adequately.

Regarding Christ’s suffering, I follow a Thomistic approach incorporating the hypostatic union into Catholic Christology. The hypostatic union is the belief that there are two perfect natures in Christ, one Divine and one human. (Council of Chalcedon, A.D. 451). It is of great import to the question of Divine impassibility that the two natures of Christ are not mixed; rather, they remain separate natures within the one person of Christ.

In Christ’s human nature, He would have experienced much of what is common to human beings: He was born, became hungry and thirsty, and, significantly, felt sorrow and pain. However, none of those things can be attributed to His Divine nature since the two natures of Christ are separate. The Divine nature of Christ is untouched by the suffering experienced by Christ in His human nature.

Therefore, with respect to the Incarnation, God suffers in His assumed human nature (that of Jesus of Nazareth), while the Divine nature remains impassible. Understood in this way, we can say that God became man, suffered, and died (in His human nature) for our sins (thereby effecting our salvation) while at the same time maintaining that God is impassible.