“Dreamt that my little baby came to life again; that it had only been cold, and that we rubbed it before the fire, and it lived. Awake and find no baby. I think about the little thing all day. Not in good spirits.”

This Mary Shelley wrote in her journal, a few weeks after the death of her premature daughter. A year later, in her novel Frankenstein, she would present the literary world with a very different spectacle of the animation of a body, a spectacle of terror, not of longing.

Yet perhaps the longing and the terror are connected. The desire to defeat death may be affiliated with hubris, or with the myth of original disobedience, but it is also connected with love. To love is to desire, for the beloved, immortality. In Gabriel Marcel’s play Le Mort de Demain, the central character states: “thou, thou alone shalt not die.” And Nietzsche writes, in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, “All joy wants eternity.” To love is to will the being and enduring of the beloved, perhaps even to see in the beloved some inherent metaphysical incapacity for being extinguished. It is to see that which in the midst of change is unchanging.

But on the other hand, to love is to see the fragility of the beloved, the vulnerability of a bodily being trapped in time, dispersed across time. Thus a mother fears for the safety of her child alone out of a crowd of children. The lover sees with terror and pity the deterioration of a beloved body, gnawed and changed by the years – and loves all the same. Time with the beloved is always too brief, as life is too brief. And so, the great dream of somehow defeating death is connected with love.

We know it is to no avail: so our myths and fantasies remind us. With a few rare exceptions, stories of return from the dead are gruesome, tragic, disappointing. Dr. Frankenstein’s creature appeared monstrous and deformed, and so too do those revenants recalled to life by unholy means. Horror stories play not only with our fears but with our desires when they taunt us with hope for the revival of the dead – and then parade before us ghosts, zombies, vampires. Our great contemporary fantasies remind us of the futility of attempting to cheat death: the undead Nazgul in The Lord of the Rings, Voldemort’s horcruxes in the Harry Potter series, and the many uneasy, uncanny, undead in A Song of Ice and Fire.

You wish to live forever? Think again.

This is the moral of the story of old Tithonus the lover of the Dawn, and of the Cumaean Sybil, and of the Wandering Jew.

The story of the dying god is a different matter. The god who dies and then returns to life is a motif of cyclical religions, and humans enter into the ritual reenactment of this sacred myth. It is very likely that the art of tragedy originated in the ritual retelling of the death and rebirth of Dionysos, and this is perhaps significant, as tragedy is essentially cyclic, connected with movements of death and rebirth and death again. The rebirth of the god gives no new promise of life for humans, but provides a sort of catharsis as the god enters into the realm of suffering.

Jesus, as a dying God, initiates a movement that is more comedic than tragic, pointing towards reconciliation and fulfillment. This is because Jesus dies not only as God but as Man. Here is our dream of resurrection and rebirth, but the beloved dead one returned is not a zombie or a ghost. “Zombie Jesus” is a pop culture meme, but Jesus resurrected is nothing like a zombie. He is nothing like what has been seen before. No doubt the fear of those who encountered him resurrected was the fear the living have of the dead yet undead, even the beloved dead. In our nightmare images of the walking undead, the ghastly revenants, death has been too potent a force, stripping away the lineaments of individuality and leaving something cold, fey. Even the three whom Jesus brought back to life through miracles – did they have difficulty adjusting again to ordinary life? Was it like waking from a sleep? Could Lazarus ever fit in again? Did his village regard him with suspicion?

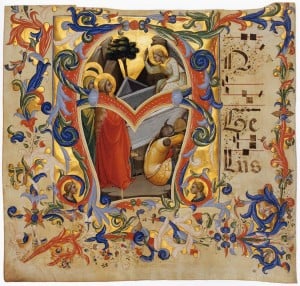

The image of Jesus, alive, is one to at once awaken and immediately dispel our fears. This is an image of life after death that is not cyclical, and not undead. Death has not stripped Jesus of humanity, but through his death all our humanity is raised.

As John Donne writes: “Death, thou shalt die.”

image: The Three Marys at the Tomb (1396) by Lorenzo Monaco, image credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Three_Marys_at_the_Tomb_1396_Monaco_Lorenzo.jpg