Are rapists monsters?

Melinda Selmys, in “Brock Turner is Not a Monster” points out:

“…it is also, equally possible that he is just a normal college kid who got caught up in alcohol and promiscuity – just like he says he is. It’s possible that he started out having sexual encounters that were pretty clearly consensual, and then he had some that were less clearly consensual, but the girls were cool with it in the morning so he figured that his behaviour had been okay. It’s possible that he thought this girl was sending off signals, that when she left the party with him she was implicitly agreeing to sex.”

This doesn’t mean, according to Selmys, that he is not at the same time a rapist:

“Because even though he probably is just a normal guy, he committed rape. He may not have intended to do so any more than a drunk driver intends to run over a child — but his drunken choices had consequences. He seriously harmed another human being in a way that will effect her for the rest of her life, and it’s reasonable to hold him accountable for that.”

Writing on the same topic, in “Why I’m Not Praying Against Brock Turner, Mary Pezzulo takes a different perspective:

When you rape, you commit a mortal sin and voluntarily turn yourself into a monster. You blaspheme Christ unspeakably by performing such a monstrous, demonic act of violence while wearing His icon, a human face. You blaspheme the Trinity by taking sexual organs and sexual intercourse– the very organs and the very act by which human beings mirror the Trinity, more than one person becoming one flesh together– and using them for an act of violence. You blaspheme the Creator by taking the organs and the act meant to let humankind participate in creation, and instead using them for destruction.

Pezzulo also reminds us that this is a case when love of the enemy is a necessary restorative of broken creation:

Love can provide the opportunity– not the compulsion, but the opportunity– for conversion and repentance and real Justice, the justice that redresses all wrongs. The justice that could provide Brock Turner and everyone like him with a chance for conversion, not without consequences, not without clear understanding and the agony of real horror at their sin– which must be more painful than pine needles in the stomach. The justice that could restore what they destroyed. The justice that brought Christ down to earth and below the earth, into the bowels of Hell, releasing the captives. The justice that draws God to allow Himself to be wounded, so that Men can be healed.

These are both writers whose opinions I respect, and I can see the merits of both arguments. In order to answer the question of whether rapists are monsters, however, we need to consider the whole phenomenon of monstrosity. To be monstrous is to be grotesque, inhuman, an aberration – to be a monster is to be violent or terrifying. The origin of the term is in the Latin, “monstrum” which signifies some distortion in the natural order of things. The root of the term, “monere” means to warn, but also to instruct: a monster or monstrosity can be a sign of instruction for us, as the medieval artists with their gargoyles and grotesques well knew. In this respect, it could be said that a rapist is a monster insofar as he deviates from the moral order, destructive and defiling. But, on the other hand, if you look at “nature” in terms of biological processes, the material of natural science, violence is disturbingly normal. Violence in sex, even. Applications of natural law in matters of sexuality must proceed with care, because if we speak simply of what is “natural” rather than in terms of what allows human nature to flourish, we are left with any number of horrors at our disposal. And throughout history, these horrors have been repeated: men killing for dominance, men raping women, women murdering their children. The stuff of Greek tragedy is visible daily in animal kingdoms, though with a sort of innocence, an intrinsic balance even amidst tragedy. Those who accuse the violent and promiscuous of “behaving like animals” are mistaken, because animals act in innocence, following instincts for survival. Humans, on the other hand, enact violence and sexual violation out of some deep-rooted hunger to destroy happiness and tear at the bonds between living things. This is the thing we Christians choose to call “original sin.”

Perhaps the most famous monster of the western literary tradition is Dr. Frankenstein’s creation. Incidentally, nowhere in the novel does the author or the narrator refer to a “monster”; but rather to the “creature.” The Creature has no name, which is one reason why the popular imagination has dubbed him with the name of his artificer. The other reason, however, is one that emerges in a close reading of the book: the creature is made in the image of its creator, he is the dark double of the hubristic scientist whose own transgression of the bonds of nature is most monstrous. Who is the real monster?

What is particularly instructive about Dr. Frankenstein’s monster is that the creature’s creator is responsible for him, responsible for the works of evil that he does, but refuses to acknowledge this. The creature is made out of bits and pieces of human bodies, but his creator who robbed graves to construct him denies his humanity. The creature is cast out, nameless, so that Viktor Frankenstein can wash his hands of the affair, distance himself from any responsibility, imagine himself pure and faultless. Thus we scapegoat the works of our own hands, when these works betray us.

This has a disturbing parallel to what is customarily termed “rape culture.” Selmys is right to note that a lifestyle of promiscuity can increase opportunities for rape. She is right to point out the disturbing reality that a nice, normal guy might also be a rapist. Nice normal guys have been a lot of dreadful things – such is the “banality of evil” that Hannah Arendt noted in her observation of Nazi war criminals. Pezzulo is also right to note that a rapist has chosen to make himself monstrous. You can be a normal, everyday person and also be a monstrosity.

But the rapist-monster, like Dr. Frankenstein’s creature, is not something that emerges in a vacuum. One does not, typically, unless one is severely mentally disturbed, say “I’m going to be a rapist now.” Those who defend rapists do so by denying that rape happened, because no one wants to be an overt rape-defender. Our culture, like Dr. Frankenstein, at once creates monstrosity and repudiates it. By calling rapists monsters, without recourse to divine mercy, we absolve ourselves of the responsibility our culture has for creating rape tolerance.

I’ve worked as an activist against sexual assault, both practically and in fields of education. And yet I have to consider the extent to which I have been blind to elements of rape tolerance in narratives I’ve accepted. Because, rape culture goes back far beyond our contemporary hookup culture. Hookup culture is a symptom of boredom, more than anything else, and as I mentioned elsewhere, it is generally profoundly boring.

A few days ago, in my piece on the topic of rape defenders, I noted that “(r)ape is nothing new; it is woven into the history of western civilization, insofar as it is a history of militarism and conquest.” Hookup culture does not cause rape; rapists cause rape, but they do so because written into our traditional anthropology (and the gendered term is deliberate) is a concept of masculine power that is connected with certain rights over a female body. When you conquer a people, you rape their women. When you’re a mighty ruler, like King David, you are authorized to rape any woman you like, and have her husband killed. Glorious warriors are rewarded with female slaves for their prowess on the battlefield. Women are given in marriage regardless of their consent. The entire concept of virginity is framed as though it were a question of whether a man has claimed it yet – not as though it had anything to do with a woman’s possession of her own body. Rape of slaves was a normal part of a young plantation owner’s sexual education. The raped woman was the dishonored woman, whether it was her fault of not (see Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles). Boys will be boys, and men have uncontrollable lusts, but women must be ladies. If you’re not a lady, you deserve what you get. Uncontrollable lusts are part of what makes a man manly. A man who hasn’t sown his wild oats is viewed as suspicion, subjected to gendered insults. Rape of men, even, is considered to be what they deserve, in prisons, and heterosexual males raping other males has often been an act of humiliation and dominance, especially over homosexual men, but also over conquered enemies, in many cultures. Women contribute to this too, perhaps because of Stockholm Syndrome, perhaps because of some deep-rooted vendetta against the violent male, or the successful female, so we slut-shame women and say things like “she’d better not complain if she gets raped.” We moon over tales of sexual predators who are reformed and taken possession of, by the inspiring female. Fifty Shades of Grey is all about falling in love with a sexual abuser, and women ate that shit up. Our pop heroes are often men who not only are casually violent but also casually run through women as though they were martinis, shaken not stirred. As long as the sexual predator is rich, good looking, and adept at murdering people, we view it as romantic. In some respects, in fact, it is romantic, because strictly speaking romance is about doomed relationships (see Denis de Rougemont), and these relationships are all doomed. The archetypes of male dominance and of female erotic power are both infected with germs of rape tolerance, and this infection goes back to the founding texts and ideals of our civilization.

Note: to recognize the seeds of rape tolerance in culture is not victim blaming, and should never excuse victim blaming. Rather, it is a matter of understanding, better, why victimization happens, perhaps the better to prevent it in future. If we are going to eradicate rape tolerance, we need to look at what is really entailed, and examine our own texts and traditions in order to see which archetypes are dangerous.

What do we do with these monsters of our own creation?

One of my favorite of G.K. Chesterton’s Father Brown Stories, “The Chief Mourner of Marne,” tells of a reclusive nobleman who, everyone believes, accidentally killed his brother in a duel. Everyone is prepared to be tolerant of the noble murderer. But when it turns out that he was guilty of murdering deliberately, through trickery, tolerance quickly turns to abhorrence:

“I wouldn’t touch him with a barge-pole myself,” said Mallow.

“There is a limit to human charity,” said Lady Outram, trembling all over.

“There is,” said Father Brown dryly; “and that is the real difference between human charity and Christian charity. You must forgive me if I was not altogether crushed by your contempt for my uncharitableness to- day; or by the lectures you read me about pardon for every sinner. For it seems to me that you only pardon the sins that you don’t really think sinful. You only forgive criminals when they commit what you don’t regard as crimes, but rather as conventions. So you tolerate a conventional duel, just as you tolerate a conventional divorce. You forgive because there isn’t anything to be forgiven.”

“But, hang it all,” cried Mallow, “you don’t expect us to be able to pardon a vile thing like this?”

“No,” said the priest; “but we have to be able to pardon it.”

He stood up abruptly and looked round at them.

‘”We have to touch such men, not with a bargepole, but with a benediction,” he said. “We have to say the word that will save them from hell. We alone are left to deliver them from despair when your human charity deserts them. Go on your own primrose path pardoning all your favourite vices and being generous to your fashionable crimes; and leave us in the darkness, vampires of the night, to console those who really need consolation; who do things really indefensible, things that neither the world nor they themselves can defend; and none but a priest will pardon. Leave us with the men who commit the mean and revolting and real crimes; mean as St. Peter when the cock crew, and yet the dawn came.”

The point of the passage is not the merciful nature of priests but the infinite mercy of God. We need divine mercy because we ourselves can often not bring ourselves to forgive the monsters in our midst; we don’t have it in us; we can’t even think about them, maybe, without it being a trigger. God is not triggered, however. Divine mercy is there to mend the unmendable.

The progressive mindset, which preaches tolerance when there’s nothing really damning to tolerate, which condemns the judgmental attitude of the religious right but then sends out the pitchforks after the monsters, fails in this regard. Because the frightening reality is that monsters are created by cultural trends, and there is no real moral guarantee set in stone that any one of us couldn’t somehow be brainwashed into doing something unspeakable. Because the monsters we chase into the wilderness are our own.

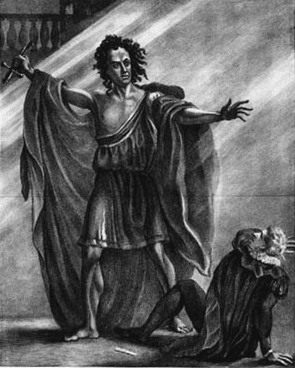

Image credit: Drawing of actor T.P. Cooke as Frankenstein’s monster in an 1823 theatrical production. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frankenstein%27s_monster#/media/File:Frankenstein_Cooke_1823.jpg