The point of this piece is not to offer a perspective on whether or not Catholics should be shocked by the brief and subtle confirmation that the not especially appealing gay character, in the Disney version of a story about a girl falling in love with a beast, is, indeed, a gay character. What I’d like to point out is that people on both sides of this conversation appear to have very little idea of the point of art, or its origins – where it’s going, and what it came from. If you’re shocked because of something edgy or perverse or manipulative in some contemporary piece, I can guarantee that plenty of earlier pieces were just as scandalous – and I don’t just mean “for their time.”

In the case of films based on classic fairy tales, what strikes me most is how much they’ve prettied up these old, gory, disturbing stories – sanitizing and sweetening them, for a mass appetite. The tales that delight us today, with their bright colors and song-and-dance-routines, with their glib morals and cute animal sidekicks, have almost no resemblance to their literary ancestors, the folk versions of these stories that were handed on through generations in an oral tradition – often a matriarchal one, which might be why so many stories are shaped around the female desire to just stop having to do housework all the time (that’s the real point of marrying a prince. Marrying just any old guy, you still have to scrub floors).

The tales of the folk tradition were often intended to frighten, not to uplift or moralize. Many were not even intended for children at all. When the Brothers Grimm went around collecting the stories of the traditional peasantry, what they found had to be bowdlerized for delicate middle-class tastes. But even the Grimm versions of these stories are disturbing. For instance, in Snow White, the princess is seven years old at the time when the evil queen turns against her. That’s already creepy. So she runs away and lives with seven dwarfs – NOT a bunch of singing curmudgeonly bachelors; dwarfs in Germanic mythology were indeed mountain dwellers and skilled at mining, but they were also dangerous, akin to “black elves”, often hideous – and often sexual predators (in other versions, Snow White actualy becomes their sex slave). After the queen poisons Snow White (after the third try: because Snow White is an idiot and keeps falling for it…or, wait, because she’s just a little kid), the dwarfs set her dead body out in a glass coffin, just as in the film – but the prince who comes along and falls in love with her – with a dead child, mind you – is a total stranger. A pervy stranger, one imagines, but he succeeds in convincing the dwarfs to let him take the child corpse back to his castle. It’s not a magic kiss that revives the princess: one of the necrophiliac prince’s coffin-bearers trips as he goes, and Snow White coughs up the poisoned apple. Whether or not the prince is overjoyed to find her warm and vital, we do not know – but, at least Snow White is safe. The evil queen does hear rumor of the wedding, and comes to see who this famously beautiful young bride is. At the door, she is given a pair of iron slippers, heated red-hot, in which she has to dance til she drops dead. Happy ending: Snow White doesn’t have to scrub floors anymore.

And that’s the prettied-up version.

This story, like many others, has nothing to do with golden dreams of romantic bliss, nor with moral lessons, but with the kind of archetypal fears and desires that lurk in the human heart, the things that terrify us when we look into our own mirrors on the wall. In Grimm’s Cinderella, the stepsisters cut off their toe and their heel, respectively, in order to squeeze on the glass slipper and fool the prince (who is oblivious, until alerted to the blood on his trail). Later, they get their comeuppance when Cinderella’s darling white doves peck their eyes out, going in and out of the wedding. In the original Rapunzel, the witch discovers that her captive has been receiving a visitor – when she notices Rapunzel’s swelling pregnant belly. In some versions, the prince is lost forever, and Rapunzel cast out and abandoned on her own. Similarly, in some versions of Sleeping Beauty, the prince rapes her inert form, then moves on: once she awakens, she finds herself pregnant with twins, and alone. In one earlier version of Little Red Riding Hood, the child saves herself from being eaten by engaging in bestiality.

These stories, at least, could be cleaned up enough to be Disney material. Not so other tales from different fairy tale traditions, such as Grimm’s “the Robber Bridegroom” (featuring cannibalism), and “The Juniper Tree” (featuring infanticide and cannibalism). And I haven’t even started on the perverse imagination of Hans Christian Andersen, or the truly deranged tales of Giambattista Basile (featuring incest and sex with snakes).

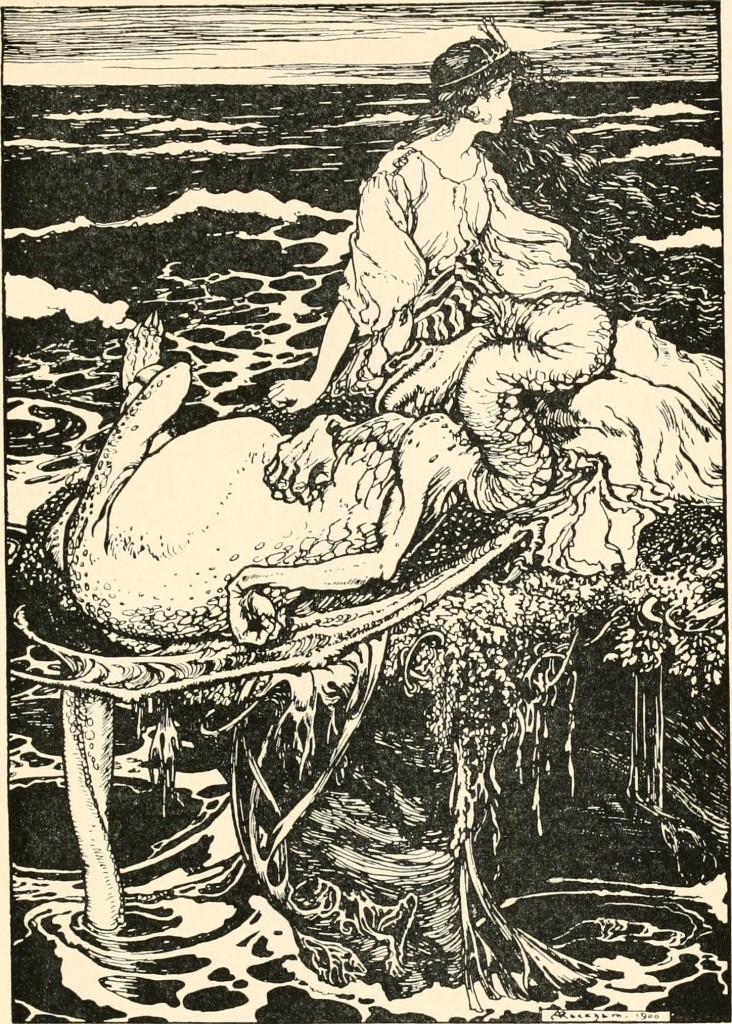

“Fairy” – the word suggests, to the post-Victorian mind, some delicate dancing creature, winsome as a flower. Maybe Tinkerbell. But actually the fay, or faeries – the Old Ones, the Fair Folk – resided in a mythic realm of shadowy terror, like humans and yet unlike, moving in a parallel flow of time, thieves of children from cradles, curdlers of milk. In some traditions the faeries were associated with the dead; in others they were like daemons, in a liminal space between human and angelic – perhaps associated with the Hebrew nephilim. In all cases, to traffic with their sort was to put yourself at risk. They might engage in relatively minor trickery, or they might cause actual blights and plagues, but in any case, the realm of faerie was an abode not of the pretty and charming, but of the unheimlich, the uncanny.

The old stories that come to us out of an older, folk mythos, have been as altered as has the idea of “faerie” itself – made into a genre that exists to be harmless…and, of course, to make a lot of money.

Now, I’m not saying that we should all rush out and acquire one of Basile’s fairy tale collections, for the amusement of our tender offspring. But I think it interesting that we have come up with an idea about art that it’s supposed to make us comfortable – that it’s supposed to be pretty and sanitary. The old myths certainly weren’t. The Old Testament isn’t. Humans are capable of great good and great evil, and capable also of creating stories that allow us to contemplate the tension between these extremes. The idea of the “fay” suggests a frightening liminal zone in which the very question of “being human” has no clear answer. Things look like us, but aren’t. Or are they?

It’s not only fundamentalist Christians who can’t stand being confronted with anything edgy or challenging; this is also a problem among feminist readers, who often mistake the representation of sexism as some sort of glorification thereof. As though we should only read stories about loving, enlightened, respectful relationships between liberated individuals.

And now, I find, I am going to say something about Beauty and the Beast, after all. Because mass-produced art is always in danger of becoming simply a vehicle for trendiness, instead of an instrument of exploration. If you want to make money, give people what they want. And it is also in danger of being used as propaganda. I agree with James Joyce that propaganda, which seeks to manipulate the audience, to violate the viewer’s freedom, is in a category with pornography. When art has an agenda – any agenda – it ceases to be treated as a thing of value for its own sake, and instead becomes a means to the end of manipulation. The aesthetic values get traded out for utilitarian ones, or “whatever will work best” to achieve the desired end, or spasm.

Now, this is NOT to say that art should not be political. All art is necessarily political, because it occurs in the public space, in the polis. The act of making art has political implications on its own – especially in a tyranny – and simply telling some stories can suffice to provoke a revolution. Or get you sent to prison. But there is a difference between art that tells a story that needs to be told – even though the Powers that Be don’t want it told – and art in which the story is only in the service of manipulating the audience. And my question is, when art is so closely affiliated with vast market forces, how can it be safe from this kind of servitude?

image credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_fairy_tales_of_the_Brothers_Grimm_(1916)_(14596094108).jpg