(PSA: trigger warning for language about rape, violence).

The summer I was finishing my M.A. in philosophy, I started receiving threatening phone calls. A male voice, sometimes low and menacing, other times high-pitched and enraged, telling me what he planned to do to me – plans involved rape, cutting, dismemberment. He called me obscene names, told me he knew where I lived, that he knew I lived with my sister. He’d do her too, he said.

For homeschool kids, we were not easily shaken. We’d survived house fires, poverty, and relative homelessness, kicks from horses, adult responsibilities in our teen years. And the façade of inviolability I wore meant never letting on that I was a victim. So at first I tried to shrug it off as a prank. But as the calls kept coming, the threats growing more disturbing, finally we decided to contact the police.

A bored-sounding officer listened to my report, then cut me off, telling me there was nothing they could do. Oh, I could buy myself one of those caller ID gadgets, if I wanted. If I could get them a number, maybe they could do something, he said. The subtext was clear: hysterical unreliable female. And not my problem, miss.

So the police were no good. I had left my hunting knives at home, but I took to sleeping with kitchen knives under my pillow, and we stacked pots and pans by doors and windows so any intruder would make a racket. My sister got a male friend of hers, a theology student, to leave an outgoing message on our machine, so that maybe my stalker would think there was a man living with us. The male friend seemed to find the whole thing amusing. It never occurred to us to contact campus security or student life. We weren’t that naïve.

In general, we got the sense that we shouldn’t make a fuss about it. And that we were on our own.

The funny thing is, I just forgot about it. Years later I found out a guy in my MA program had been unstable and obsessed with me, and I was reminded of the summer of the phone calls, when I was writing a thesis on Nietzsche, and drinking gin, and sleeping with knives under my pillow. Maybe he was the one? It was an academic conundrum.

That’s just how inundated one can be in a culture of violence against women. That nightly death and rape threats just became part of the tapestry of that time, along with the fun parties and quoting from Birth of Tragedy loudly, to irritate the uptight. That I lived in fear, but just forgot about it.

It wasn’t the only thing I had to forget about, after all. Just one episode out of many. Like detectives on a crime case in classic murder fiction, you develop a sort of gallows humor about such incidents, maybe because it’s a little shocking to people, when you laugh at inappropriate things. Shocking people is a way to maintain power, after all. And humor is how you cope, which is why social justice warriors laugh extra loud when playing Cards Against Humanity.

I was reminded again of the summer of the phone calls when I witnessed, recently, a rising young Republican politician, a graduate of the school where I formerly taught, defending Roy Moore. Most of his followers applauded him, but one woman was perplexed. What about his victims? she asked.

Fake news, he said.

And suddenly the full scope of that overworked Trumpian phrase, and all its implications, became clear to me. Maybe I was a little slow to make the connection, but once I saw it, I realized the bigger picture it entailed. I’d been looking at the “fake news” phenomenon only as a typical fascist governmental crackdown on journalists, or as a philistine disregard for letters, learning, and evidence. To insist on accuracy is to be a “liberal elite,” I’ve found. Even if one is dirt poor.

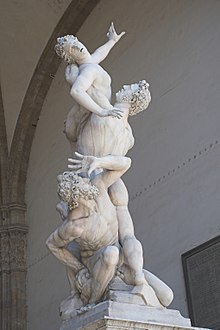

But dismissing stories, specifically of sexual assault or violence by men against women, is as old as civilization. All the Greeks blamed Helen for being raped by Paris, after all. Raging armies of men fought for ten years, and in the end the great city was sacked and burned, women ravaged, babies dashed against walls – and it was all her fault. Helen, the destroyer. We get the stories of the battles and voyages from the perspective of the male heroes, but where is there a place for Helen’s voice? And so on, down through history and literature, we have the stories told by men, dismissing women, blaming them. Mary Magdalene, the most faithful of Jesus’ disciples, was disbelieved by his male followers when she brought witness of the Resurrection. Women were forced into socio-economic marriages without regard for their preference in the matter. They were barred from preaching, from universities, from the practice of law or politics. Occasionally, with great effort, a woman like Elizabeth I could rise to power, but doing so usually meant trampling on other women, as Elizabeth’s mother Anne trampled on the rights of Queen Katherine, wrongly divorced and cast aside. And Anne herself, when she professed innocence of witchcraft and adultery, was disbelieved. Her head cut off. And hers wasn’t the first to roll.

For three thousand years, Western history has been the story of men speaking over women, rewriting women, silencing women. “For most of history,” Virginia Woolf writes, “Anonymous was a woman.”

Today, when I talk to the many, many women I know who have been assaulted, very few of them have a story of justice to tell. Some were told “you’re making it up.” Others were forced to be silent, threatened with expulsion. University and workplace programs against sexual misconduct tend not to work, because HR and Student Life are invested in protecting institutions, not people.

It’s no accident, I believe, that the demographic most prone to yelling FAKE NEWS is also invested in protecting sexual offenders from inconvenient truths. That men in power tend to abuse and violate women is only one inconvenient truth – others include climate change and systemic racism – but the oldest and most inconvenient truth of all is that yes, there is such a thing as a patriarchy, and yes, it justifies the violation of women.

Nietzsche (whom I was studying while a male student in the same program fantasized about cutting my breasts off) wrote about how the power is associated with the power of naming. He was talking about the right to label “good” and “evil” – but his observation is especially telling when we look at gender relations. Adam named the animals, then he named Eve. Women have to take the names of men. And men, for most of history, have felt entitled to label what is or is not true. As women, in the fields of arts, academics, journalism, or law, we have had to look hard at the field of evidence, lay claim to facts, produce proof, over and over again, in order to be taken seriously, over against opponents who just express whatever opinions happen to come to mind.

I’m not saying men don’t also work hard and produce reliable evidence in writing or scholarship – but, there’s an ease with which the stereotypical “mediocre white male” can market himself as infinitely brilliant and charismatic, which is still denied to women. That’s why we get angry. That’s why we sound shrill. When everyone around us is responding to our pleas for justice with indifference, or shouting us down with FAKE NEWS, eventually we get to feel that yelling into an unhearing void is the only option left.

The same people who like to talk about FAKE NEWS like to tell us, as women, that we should be docile and submissive. But, having just celebrated the season of Advent, hearing the stories leading up to the birth of Jesus, I have a vision before me of another way to be. It’s not just a choice between helpless rage and helpless submission. The scriptures that tell of the coming of the Messiah give promise of a Prince of Peace who brings justice to the oppressed.

Every valley will be exalted, and every mountain and hill laid low…

I love listening to that part of Handel’s Messiah, blasting it on my speakers as I drive through coal country, past the homes of the poor, who freak out on meth and survive on disability checks, past the homes of the rich, who voted in a sexual predator. Past the churches where the biggest source of pride is the fancy new sign outside. In spite of everything, the story of Christ and the message of the Gospel makes me feel hopeful, determined. Like Mary, whose Magnificat gives glory to a God who casts down the mighty from their thrones, and fills the hungry with good things, while the rich are sent empty away. Mary, who chose to obey God, and not men.

The story of the Birth of Christ is one in which, every moment, Mary is imperiled because of the unjust social structures around her: she could have been stoned for adultery; she was oppressed by occupying Empire; her child was threatened by a jealous megalomaniacal king. But the God who we believe became human in this season is one who brings justice to the oppressed. This is the Good News we celebrate. We will be seen, heard, and protected. Our stories will not be overwritten or shouted down. We are loved.

image credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Rape_of_the_Sabine_Women