by guest contributor William M. Shea

“Entry into Christian existence requires the simultaneous discovery of our finiteness and our thirst for the infinite, to which no culture can give satisfactory answers.”

(La Croix June 15, 2020)

The squabble over the atheism of Dawkins, Hitchens and San Harris has lost steam while atheism generally has not. Even bona fide atheists have been critical of the New Atheists intellectual stance for a variety of reasons. One of the most ( there are many) devastating critiques by a Christian thinker is Nicholas Lash’s “Where Does The God Delusion Come From?” (New Blackfriars 16/08/2005), now fifteen years published and still brilliant. Besides pointing out the frequent misunderstandings of religion and theology as well as the equally frequent misuse by Dawkins of terms as basic as ‘science’ and ‘religion,” Lash makes it clear that what is at stake in the squabble is the serious issue of the limits of human enquiry, and scores Dawkins for being on the wrong side even of the meaning of ‘science.’

But enough of the argument about whether God exists and whether Christian education of children amounts to child abuse. It is well past time for a bit of ecumenism, for building a common understanding of our humanity and its implications. That can’t be achieved, I am sure, by more arguments, more invective, more atheism vs. religion as stark alternatives. I had my fill of that by the time I had finished my doctoral dissertation and a book, both on American Naturalism. What I’m interested in is how the two sides can understand each other. That calls for a bit of dialectic, beginning with some suggestions on what we can learn from one another and a shot at how the two sides might “fit.” If Catholic and Protestant Christians can pull that off, why not theists and atheists? In other words, do religious people have something to learn from the atheisms advanced over the last two centuries, and vice versa? I will start, in this post, with five suggestions about what Christians can learn from atheism and pass on in the next post to suggestions on what atheists can learn from Christians.

- By assuming that what Christians mean by God is just another being in addition to all the other beings, atheisms force Christians to recognize that what they mean by God is NOT a thing, a being, at all. In fact put it this way, God is No Thing among other things, but not nothing and certainly not everything. What God is and isn’t requires an intellectual and historical journey for an individual and for homo sapiens as a whole. It is at least in part the pressure put on Christians by atheist philosophers that propels us on that journey.

- Because the atheist challenge is not only about what God is but also whether God is, Christians must recognize that what they assume (the existence of God) in their religious life is not at all evident to other human beings. The theist must say just why they think or believe and not take the existence of God for granted. The history of “arguments” for the existence of God is conditioned on the question of fact: Does God exist? And how do we know that fact if indeed we do? What many call “philosophical theology” exists primarily to answer those questions for Christians, and atheism contributes a good reason to be very careful how we answer the questions. By its critique it should make Christians a bit more self-critical. Our Christian bubble is not impenetrable to atheists’ critique. Alas, on the question “How do we know God exists?” Christians are still all over the lot.

- When we begin to explore our reasons for knowledge or belief we quickly realize that our thinking and language about God (and for Christians about Jesus) is greatly reliant on “tradition” and “community.” We are not alone in our quest, nor are atheists in theirs. We are part of a culture and so are they. Our conversation is not between one Christian and one atheist, but between two subcultures, two bubbles so to speak, each of which is formed in part by suspicion of the other, even by rejection of the worldview of the other. The participants in a dialogue have the need not only to break through the individual convictions but through the high and heavy walls of tradition and community. If we do maintain the distinct bubbles of language, conviction and culture, exclusive of each other, how do we come to understand each other? How do we benefit each other? Are we condemned to evangelize each other till the end? Or can we put aside shrill and silly polemics and talk constructively about the issues?

- Atheist philosopher John Gray in his excellent book Seven Types of Atheism ends on a surprising note. He claims that existence is “a mystery,” and that religion and atheism are not far apart at this point. Well. Since the theist claims that existence is a Mystery, capital M., maybe there is here a promising starting point for constructive discussion. What do we mean by “mystery,” and what makes the difference between capital and small m/M? Even atheists (not to say agnostics! ) might admit that they don’t have all the answers, and perhaps even for some they will never have the answer to that very basic question, “Is the cosmos ‘mysterious’ in any sense at all?” If so, atheists have made a signal contribution to a dialogue that believers not only agree with but can admire even given the term’s ambiguity.

- A claim is made by many atheists that religion, religious behavior and even religious thought proceed from passions and emotional needs rather than reason and intelligence. God knows religion is both passionate and emotional, at least in my case. When I pray, for example, I am most surely engaged in wish, hope, desire, love, emptiness and fullness, and I am searching and sometimes even joyful. Take Alec Ryrie’s recent Unbelievers: An Emotional history of Doubt (Harvard University Press, 2019) and watch him run through 200 years of especially British atheism, clearly establishing its emotional and passional foundations. Another starting point for dialogue: atheism and theism do differ in content and world view, but can we agree that passion is foundational in both cases? And how do atheists differ in this regard from religious people if they do at all? We may be able to dispense with denigration and polemics on both sides, and try a little respectful conversation.

- Atheists in their intention to advance the scientific attitude and even to sometimes claim that atheism is based on science, have uncovered the crucial role of doubt not only in science itself but in the everyday knowing and deciding in which we all engage. Doubt is an act ingredient to every quest for knowledge and search for the good. Doubt finds its locus in reality whenever a human being asks: But is that so? And I sure? What in heaven’s name is that? Why should or shouldn’t I (or we) change our mind(s) on our path(s)? Ye gods, could I have been mistaken? Is this just too good to be true? Belief reveals itself as proposal, as assertion that is not yet knowledge and which is invariably liable to doubt. The empirical limit to human intelligence (knowing) maintained by atheists is doubtful itself, isn’t it? There is ample room for discussion here. And atheists can put this question to themselves as well as to believers. Let’s talk about doubt.

William M. Shea, Ph.D.

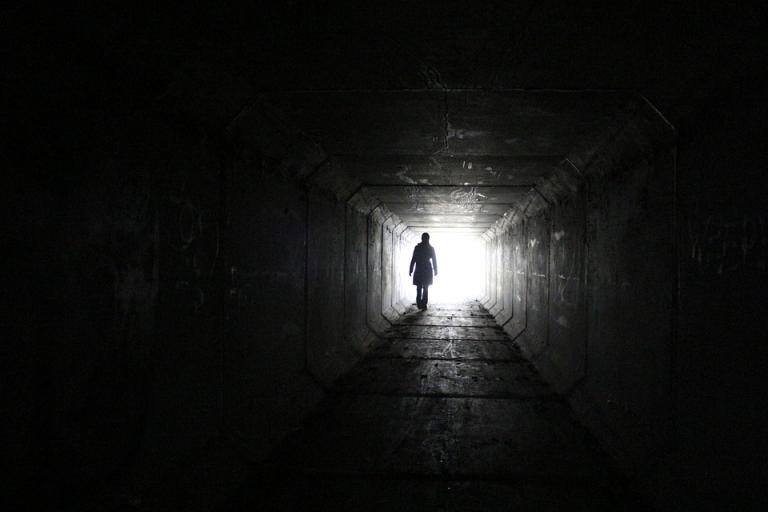

image credit: pixabay-photos-tunnel-silhouette-mysterious-899053.jpg