By guest writer Alan B. Ward

I have been reading the book, “Jesus and the Disinherited,” over the past few months as part of the online Renovaré book club. Howard Thurman’s classic was first published in 1949. While some of the specific content makes it clear that Thurman was a “man of his time,” I’m struck by how much of the message remains relevant today.

Thurman directs his message to those “with their back against the wall.” Being a man of his time and an African American, he focuses primarily on the plight of the “American Negro” in the Jim Crow segregated South. However, he acknowledges that many populations around the world find themselves in a similar predicament. For example, Thurman was deeply influenced by the experience of Mohandas Gandhi in India, where the Indian people were brutally oppressed by British colonizers. Many of Thurman’s ideas about non-violence came together after his visit to India and meeting with Gandhi in 1935–36.

Without question, many people in our own nation have felt like they have been living “with their back against the wall.” Especially over the past four years, during the Trump Presidency, women, people of color, and even the planet itself have been pressed down upon.

Given that reality, maybe it’s worth thinking about what Thurman has to say to us in 2021.

After introducing the plight of the disinherited, Thurman proceeds to place Jesus in his historical context: Jewish, poor, and living under Roman oppression. In other words, the historical Jesus lived “with his back against the wall,” and thus, Thurman suggests, he can relate to the plight of the disinherited. The “religion of Jesus” (not to be confused with Christianity as practiced in the Western world) has much to offer them—wherever and whenever they live.

The bulk of the book is three chapters that discuss what Thurman calls “the three hounds of hell that dog the footsteps of the poor, the dispossessed, and the disinherited.” The first of these hounds is fear. There are many fears with which humans struggle, but the specific fear that plagues the disinherited is suffering violence at the hands of the dominant power. The weak come up with all kinds of tactics to avoid being killed by the strong.

Long before he decided to run for President, Donald Trump weaponized fear, specifically, the fear of the other. He intentionally focused on white people’s angst that people of color were “taking over the country.” Fear makes us define ourselves relative to others. When others gain new freedom, I fear losing my privileged status over them. We fall for the lie that the only way they can possibly gain more is for me to have less.

Perhaps this is why Thurman says that the only remedy to fear is being secure in one’s own identity as a child of God. When one is secure in that identity, what others think of me doesn’t matter. While being a child of God is an essential starting point for overcoming our fear of the other, Thurman says that it’s really not enough. In addition to knowing who we are, in general, we need to know what we are specifically. In other words, what gifts has God given me uniquely and what does God call me to be individually. Knowing who we are and what we are is the best antidote the disinherited can have as they stand against fear.

The second hound that Thurman discusses is deception, which has long been a tactic used by the weak to avoid the wrath of the strong. In fact, deception seems hard-wired into creation. Animals have evolved attributes and they adopt tactics that help them deceive predators. Similarly, deception is alive and well in human relationships. Children learn to use deception to manipulate their parents to get things they want. Likewise, Thurman talks about how, in a traditionally male-dominated world, women employ deception to get what they want. I personally think this is one of those places where the content is a bit dated. Deception is hardly unique to women; it’s a survival technique used by both sexes to manipulate.

Certainly, Donald Trump is a master of deception. He has convinced those who follow him to believe in alternative facts. If you believe “the sky is purple,” then a whole new perception of reality is possible. That latest installment of the Trumpian fantasy rests on a baseless claim that the hero was the victim of a massive voter fraud that has “stolen” the election from him.

Thurman talks about how lies become habitual. As he puts it, “the penalty of deception is to become a deception.” Donald Trump is a modern-day example. He has indeed become a deception—the living embodiment of a lie. The events of the past week in our nation show that he has clearly drawn many others into his toxic fog of deception. Perhaps out of fear of what will happen if they cross him, they do his bidding. According to Thurman, the only true remedy to deception is uncompromising sincerity (or integrity.) Some attempt to “hold the line” on certain issues and compromise on others in order to survive. However, it’s hard to straddle the fence between honesty and deception for long. The Apostle James warns us that, “A doubleminded man is unstable in all he does”—James 1:8, KJV. In other words, eventually you’re bound to fall off the fence!

Last but not least, Thurman discusses the hound of hate. Published in 1949, Thurman’s book talks about how hate of the Japanese became acceptable in the aftermath of World War II. He explains how hate validates our negative feelings and provides a sense of significance to our endeavors. Hate, says Thurman, provides a “tremendous source of dynamic energy” that temporarily fuels our enmity. Thurman describes how normal American life didn’t prepare young men psychologically to become “human war machines.” He says that “Something radical has to happen to their personality and to their overall outlook to render them more effective tools of destruction.” In other words , they have to be trained to hate the enemy. The problem is that once a person becomes “disciplined in hate,“ they eventually can’t discriminate whom they hate. Thurman says that, whatever temporary “benefits” hatred may bestow, it ultimately “turns to ash,” and consumes the person, because it “guarantees a final isolation from one’s fellows.”

While we’re not engaged in a war against a foreign enemy in 2021, President-elect Joe Biden has correctly suggested that we are in a “battle for the soul of our nation.” Our partisan divide has never been greater. Donald Trump has done nothing to close that gap; in fact, his words have encouraged a militant reality. He regularly addressed his followers via social media encouraging them to do whatever it takes to “make America great again,” and “take back our country from the godless liberals.” Trump’s anti-other rhetoric has had the effect of making hatred acceptable. He has created convenient scapegoats to blame for society’s ills: e.g., people of color, Muslims, immigrants. It’s not that such hatred is a necessarily new, but Trump seems to have fanned the flames. One no longer has to hide their ill will toward these scapegoats. Anyone who questions this interpretation of events need only look as far as the events of January 6, 2021 at the U.S. Capitol, to confirm how public hatred has become acceptable in our present climate. If you need a single image to encapsulate it, consider the individual strolling through the rotunda waving the Confederate Flag.

Jedi Master Yoda (from Star Wars) once said: “Fear is the path of the dark side (which was all about deception). Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate. Hate leads to suffering.” It’s a slightly different list of traits (mentioning a couple of pups of the hounds of hell: anger and suffering), but the essential message is the same. These ravenous canines feed off of one another. They reproduce within the individual they inhabit and ultimately consume them.

Thurman argues that, “Jesus rejected hatred because he saw that hatred meant death to the mind, death to the spirit, death to communion with [God]. He affirmed life and hatred was the great denial”

What is the remedy, then, to these voracious scourges on human life? Is there a kind of mace that can used to repel the hounds of hell? Jesus suggests the answer is love. Of course, the cliché is that the Gospel in a word is love. It seems too simple an answer; yet anyone who has tried to actually live out 1 Corinthians 13 (and not just read it at a wedding) will tell you how hard it is. The religion of Jesus makes the love-ethic central. (The same ethic was also key to Gandhi’s teachings.) Jesus said that we should love our neighbors—and then demonstrated what he meant. As Thurman says it, Jesus shows (e.g., in the parable of the Good Samaritan) that “every [person] is potentially every other [person’s] neighbor.” He not only told stories about love—but he also lived love. He reached out the least, the last, and the lost. Jesus modeled agape love in all of his relationships and interactions not just with friends but also with “enemies”—with intimate allies, with the Jewish leaders (who collaborated with Rome), and with the Romans oppressors themselves. He gave the ultimate demonstration of love when he died on the cross.

In the words of Martin Luther King, Jr., “Hate cannot drive out hate. Only love can do that.”

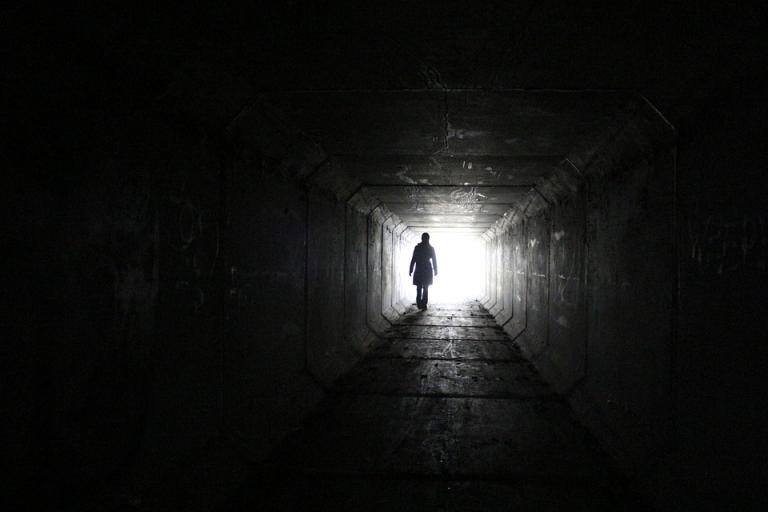

Image via Pixabay