Sometimes we want to know why people do the things they do.

In my field of Behavior Analysis, we have a simple tool to figure out what drives a person to behave a particular way. The technical term is a “Functional Analysis.”

Motivations for Behavior

Human beings, along with most other animals, do things for one of these reasons:

- To gain some item (like candy, a new car, or that thing on the top shelf)

- To gain attention (which is essentially why we post anything on social media)

- To get away from something unpleasant (like excusing yourself from some awkward encounter)

- To achieve some sort of pleasant sensation (I’ll let your imagination do the work here)

A Word About Attention

Before I go on, I want to say a word about the concept of “attention.” We’ve all seen someone acting in a dramatic way, and heard someone excuse it by saying “Oh, she’s just doing that for attention.” It seems dismissive, and doesn’t appear to get to the heart of the person’s feelings or needs.

However, in Behaviorism, “Attention” is a broad term which encompasses any kind of human interaction. It could be applause, but it could also be the desire for connection, affection, acknowledgement of needs or even existence. So as I speak of behavior for “attention,” try to disregard the negative stigma that expression often has and think of it more as the fundamental need we have for human connection.

Deconversion as a Behavior

The most obvious motivation for deconversion would be Escape. You are moving away from religion.

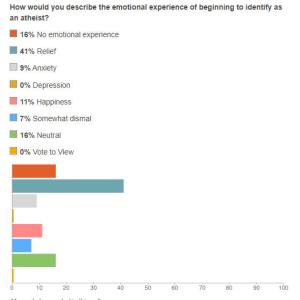

Remember that Escape behaviors are done in order to get out of some unpleasant situation. A very commonly reported feeling upon leaving religion is happiness, or more frequently, relief. Consider the results of an online poll I conducted on the subject, below:

This suggests that there is something about religion which is aversive such that people want to escape it. Or at the very least, there is nothing rewarding about the religion such that people lose interest.

What Motivates Conversion

Presumably, individuals join religion because there is some motivation to do so. Again, consider the motivations of behavior listed earlier in this article. They probably don’t join to get some item. The most probable reason is attention, given that religion has inbuilt community. A child growing up in a religion probably associates the religion with parental, adult, and peer approval.

Another reason to join religion might be the pleasant sensation, which is especially true when one’s religious environment encourages or provides deeply spiritual experiences.

A third reason to join religion would also be escape. The individual has some problem in their life to which religion becomes the solution. In fact, most conversion models suggest that an individual is attracted to religion because they have some sort of conflict, problem, or perceived need in their lives to which religion appears to be the solution.

Whatever the case, if one joins the religion for one of those reasons, they likely leave the religion because they are no longer receiving any kind of reward for remaining.

Attention

Perhaps the individual was part of the religious community for the attention it provided. If they leave, it must mean that something changed in terms of the attention. What one finds is that frequently the deconversion occurs sometime after a move. Perhaps the individual goes to a new church. Perhaps they move to a new city for work purposes. Perhaps they join the military. But most frequently, the deconversion occurs after they go to college.

One can assume, therefore, that they are no longer receiving the attention which was reinforcing their church attendance. So the church loses its reinforcing power in their life. But there is a further possibility than this. The individual is likely now having their attention needs met by their new, non-Christian environment. Consequently, the church no longer becomes necessary as a source of attention. Or, put differently, they have discovered a community of support outside of the church. Now while this may become a reason for disaffiliation (meaning they drift away from attendance or interest in church), it doesn’t explain deconversion, wherein the person becomes overtly opposed to religion.

That is, unless, the person is receiving attention in their new circumstance specifically by opposing religion. Research suggests that young people are often given peer approval for criticizing religion or religious authority.

Sensation

Once again, as the person transitions to a new environment, they may no longer experience the sensations that came with worship activities. This may even occur while in the church. There is reason to believe that the ecstatic sensations that come with some types of religious participation do diminish over the course of one’s religious career. And if these experiences were the motivation for religious participation, their absence may induce a loss of religion. But again, this seems more likely to result in disaffiliation than in deconversion.

Escape

Herein lies the key to deconversion. Most models of religious conversion indicate that religion is most attractive to those experiencing some sort of difficulty, dissatisfaction, or other aversive circumstance to which religion appears a solution.

Now often, the religion is that which makes these circumstances clear. The classic method of Christian evangelism, for instance, involves explaining to the individual that they exist under a state of sin or other kind of inherent difficulty that may be removed by following the religion.

Now as with the other above motivations, if the person is no longer experiencing the sort of relief that religion was supposed to offer, they no longer have reason to follow the religion.

However unlike the above ideas, escape may best explain deconversion rather than mere disaffiliation. If the religion itself becomes aversive, the individual will not merely seek to escape, the individual will come to actively dislike the religion, and to associate the religion with unpleasantness.

Consider, for instance, the dentist. If one goes to the dentist to have a tooth drilled or removed, they have experienced pain and other unpleasant things. While there is nothing actually wrong with dentistry, and a number of things good about dentists, the individual is now triggered, so to speak, by the thought, sight, or other things associated with the dentist. An unfortunate experience has become the occasion for active dislike of the dentist.

It is very frequently the case that deconverts find things associated with religion – such as religious music or mention of religious terminology – aversive.

Something Else

There is one final consideration in terms of what might cause active opposition to religion, and that is if such opposition is actually positively rewarded by one of the above stimuli. An online atheist receives a lot of attention – both positive and negative – for saying controversial things about religion. Consequently, the move away from religion might have one motivation, whereas the active opposition to religion may have another.

About Functional Analysis

It is likely to be said that the above analysis is overly simplistic and does not take into account the specific arguments associated with atheism, such as Bible problems, the evil and suffering in the world, or the sins of the church itself.

What to keep in mind in this particular article is the nature of “functional analysis.”

In the world of Behavioral Analysis, one does not assume the existence of mental states, reason, emotional states and the like in order to explain behavior. This is because such states cannot be seen or functionally defined. They are just said to exist because the behavior exists.

One might say, for instance, “I read a lot of books, realized that religion was untrue, and then I left religion.” This is a chain with three links. The first link is the stimulus (books) the second is a mental state (realization), and the third is the behavior (exiting religion).

Behavioral analysis discards the middle link, which cannot be observed, and simply says “reading books became the condition under which he left religion.”

Does this mean that books cause deconversion? It might if one were to observe that certain books read under certain conditions were consistently followed by deconversion. More likely what it would mean would be that the content of the books would create a circumstance under which the religion loses its motivating power, or is caused to become aversive. However, this assumes a sort of self-awareness on the part of the person who said this about themselves. A more accurate conclusion would come from an outside observer who was able to take account of the circumstances, environment, and behaviors which preceded the religious exit.

Objections

In an on-air interview on my research, I made the statement that “deconversion is an escape behavior.” And that, “they leave religion because it is aversive.” Making this statement in the presence of a listening audience elicited some criticism.

The criticism had to do with the idea that those who reject religion aren’t escaping it because of some antipathy or bad experience, but rather on the basis of intellectual honesty. One can no longer practice a religion they do not believe.

This was partially my fault because I was using the technical language of behavior analysis. And in order to understand the thrust of the statement, one must know a few things about behavior analysis.

Under behavior analysis, we suppose that behavior always flows in the direction of reward and away from that which is not rewarding – whether by being uninteresting or being uncomfortable.

“Aversive,” in behavioral terms, means anything that drives behavior away from that thing. One need not ask what the person is thinking or feeling under the circumstance, one need only observe the effects the circumstance has on the person’s behavior.

This may sound particularly cold and uncaring for the person him or herself, and it would be in the therapeutic sense, but anthropology and sociology are not therapy. They do not exist for the goal of treating a person. They exist merely to understand the form and function of the behavior. These data may be useful in the long term for treatments of one kind or another, but in the short term, we are only interested in what the behavior looks like.

I look at religion as a behavior – as one must do if one is cataloging it by observation. If a person tells me that “I once called myself a Christian, but I now call myself an atheist,” this is what we would call a “verbal behavior.” The act of describing oneself as some thing and not another thing is a learned behavior that relates to past experience. As a scientist I have to ask myself not what do they say, but why do they say that. Meaning what was the chain of events that led to the person changing the words by which they describe themselves.

If a person tells me they left religion because they did not find any evidence to continue believing it, or they found evidence against it, or they discovered that faith was not the sort of thing that ought to drive a worldview, what that person is ultimately saying to me is that their ideas were incompatible with religious behavior. This very incompatibility would qualify as the aversive event by way of a phenomenon known as “dissonance.” Dissonance describes the uncomfortable feeling of hold on to two ideas which contradict one another. Finding a way out of mental discomfort is still a form of Escape.

Religious Behavior

Let’s qualify what is meant by “religious behavior.” Ultimately, religious behavior would break down into two categories: private and social.

As a demonstration of this, let’s consider the prayer a religious person would typically say before a meal. Under one circumstance, when dining with other Christians, the person might stand up and say a prayer out loud in the presence of the others. This is surely a social behavior. The person would not stand and say a prayer out loud when isolated away from others. They might say a prayer, but probably in a different fashion than they would in the presence of others.

Now consider another person who would never actually stand and pray out loud around other people. This person, instead, says a prayer quietly or in their head. Possibly, when not around other people, this person will close their eyes and fold their hands. But in a restaurant or cafeteria, this person merely pauses for a moment and tries to say a prayer in his or her mind in a way no one else will notice.

This is surely a private behavior and meant not to be observed.

Religious behavior ultimately boils down into one of these two categories. Wherein church attendance for the sake of interacting with others – singing out loud in church while raising one’s hands – are public behaviors one may never do in private. On the other hand, reading one’s Bible and praying alone are private behaviors not maintained by any attention one may receive, or by any conformity to the behavior of others.

Now the person “stops believing” for some reason known only to themselves or anyone they tell. One no longer attends public gatherings because these events no longer reinforce those behaviors. In fact, attendance to those events would be aversive, not because the people or place are oppressive, but because the events themselves are incompatible with one’s current belief structure. And because they no longer reward or reinforce the ideas the person holds, they are, at best, absorbing time the person could be spending doing things they prefer, and at worst, punishing by way of associating with ideas the person has rejected.

There is also no longer any reinforcing value to private prayer or scripture reading. Those behaviors both have lost their reinforcing value and, as a result, discourage rather than drive behavior.

Often one finds that when any organism has lost interest in something they once found reinforcing (often by way of satiation: they have had enough and it no longer interests them), they attempt to find some replacement. While peanut butter and jelly sandwiches may have value for a while, they start to become old, and the child will try to find a different sort of food to replace them.

One sees a similar sort of thing happen in deconversion. The deconvert will attempt to find new kinds of social events or circumstances that substitute in reinforcing value for the church community. Or they find new private preoccupations to replace devotions, new music to replace religious music, and new subjects of interest to replace theological concerns.

All of this qualifies religious behavior and trappings as aversive in the same way that food becomes aversive to someone who has already over-eaten.