In a world seething with violence, how does the Church live out Jesus’ command to love our enemies? What does the Bible – and specifically Jesus – really say about how we’re to consider warfare and violence as people of faith?

In a world seething with violence, how does the Church live out Jesus’ command to love our enemies? What does the Bible – and specifically Jesus – really say about how we’re to consider warfare and violence as people of faith?

In a bold new book called Fight, Evangelical pastor and best-selling author Preston Sprinkle sets out to answer these important questions as he makes a compelling case for nonviolence. Drawing from his expansive theological background, research and countless interviews, Preston addresses questions such as how to reconcile what seems like a vengeful God of the Old Testament with the forgiving, nonviolent Christ of the New Testament; how America should defend herself against aggression; what Scripture teaches about Capital Punishment; and whether Christians should kill in self-defense.

We had the opportunity to ask Preston some questions about his book and his own reluctant journey toward nonviolence — as well as his potentially unpopular position within his faith community. [For more conversation on Fight, visit the Patheos Book Club here.]

In your new book, Fight, you engage one of the most hotly-debated questions of our time: What is the Christian response to warfare and violence? What, in brief, is your response?

In your new book, Fight, you engage one of the most hotly-debated questions of our time: What is the Christian response to warfare and violence? What, in brief, is your response?

I believe that Christians should not respond to evil with violence. Now, this does not mean that Christians shouldn’t do anything to confront evil. Quite the opposite. Christians should aggressively respond to evil but with the means that Christ has demonstrated and taught. And Christ neither demonstrated nor taught believers to confront evil with violence.

As an Evangelical Christian, you’re taking an unpopular point of view on warfare and violence in this book. Yet you make clear that you own guns, vote Republican and love sports and even violent movies. So, what inspired you to write a book on non-violence, and whom did you write it for?

It’s a strange world we live in where being Evangelical and advocating for nonviolence seems to be at odds! But yes, for some reason my view is not very popular among my fellow Evangelicals. Why is this? If I can be so bold, I think that many (not all) who advocate for a violent response to evil, or who believe that America’s military can solve the world’s problems or keep evil at bay, have been more shaped by our American militaristic culture than the Bible.

The inspiration to write this book stems from a passion to be biblical in all areas of life—even if it offends our inherited presuppositions and beliefs. I want to shoot my enemy just as much as the next guy. But loving him will do more for the kingdom of Christ than blowing his head off. So I wrote this book for people like me: Confessing Christians who are on a quest to understand what the Bible says about warfare and violence, even if it offends our intuition.

You grew up, you say, “like many Evangelicals,” enamored with war and convinced that war and military might were the best way to fight evil. In fact, you wondered how someone could actually read the Bible and still endorse non-violence? And yet, several years out of college, as a Seminary student, you became a pacifist. What happened in those intervening years?

It was actually not until after I completed my Ph.D. when I became a “pacifist,” or, as I prefer, an advocate for nonviolence. (The term “pacifist” is too loaded and misleading, so I don’t prefer to use it.)

For most of my years as a Christian, I never really studied what the Bible says about violence, and yet I had strong opinions that Christians should use violence to confront evil. I didn’t feel the need to consult the Scriptures. I just followed what my Christian subculture and Ronald Reagan told me. If someone bombs you, you bomb them back harder. If using violence can save innocent lives, then it’s perfectly okay. But I never stopped to wonder whether Jesus might have a different way to confront evil. So I started reading the Bible with the question of violence in view and was shocked at how little Jesus agreed with my presuppositions.

You say that evangelicals have a “strange affection for military power and an odd history of being pro-war.” How have militarism and religion become so inter-twined in the American church and why is it problematic? What would it take to unravel this relationship? And what’s at stake?

Evangelicalism and militarism became kissing cousins during the 1970’s and 1980’s, when being Republican meant being pro-family, anti-abortion, anti-gay, pro-militarism, and—if another nation deserved it—pro-war. Any protest against militarism and war meant that you were a liberal and a communist. Thus the courtship began.

This relationship still continues today. However, Gen Xers and Millennials, who have lived their formative years in a post 9/11 context, are questioning such hyper-militarism. This will be an important turn for the Evangelical church. The new generation of Christians aren’t so easily convinced that America is the hope of the world (since Jesus said He was), or that Jesus didn’t really mean that we should love all our enemies.

We recently featured a powerful book by a young Iraqi vet, Logan Mehl-Laituri, called Reborn on the Fourth of July, in which he recounts his faith journey from a patriotic American to a conscientious objector after serving several years in the war. You also have several war veterans endorsing your book. What is the role of veterans in this discussion? What can we learn from those who have been on the frontlines about the relationship of warfare and faith?

That’s a great question! I intentionally sought out several friends who were military vets to see what they thought about warfare and violence. I was pleasantly shocked at how against it they were! I was shocked because it’s easy for us civilians to think that being nonviolent means that we are dishonoring our veterans. Maybe some would feel offended, but the ones I’ve talked to are nonviolent because they’ve seen hell. They’ve seen war. And they’ve seen that even if America wins, everyone loses.

So I think it’s important to listen to the stories and pain of our military veterans. I think they have an important voice in the discussion.

Many Christians associate the Old Testament with violence, and are troubled and by a God who seemingly advocates violence. You have a different perspective on the violence in the Old Testament…

Yes I do. And I take four chapters to unravel this perspective! In short: Yes, there’s a lot of violence in the OT, and yes, violence is sometimes sanctioned by God. However, not all of Israel’s violence was commanded by God. A lot of their wars were deemed sinful.

Even in the wars sanctioned by God, Israel was not allowed to be militaristic. This is something that I think many interpreters have missed in reading the Old Testament. Even when violence was sanctioned, militarism was not. Never. Everywhere it’s prohibited; everywhere it’s critiqued. But you’ll have to read the book to see why!

Also, we have to read the OT as an unfolding narrative that’s headed toward a goal. And throughout the OT, we see God moving Israel further and further away from violence and toward peace. When the OT ends, the reader anticipates a kingdom of peace, a Messiah who suffers instead of kills. Thus, the OT flows naturally into the NT.

Ironically, in the end, your book challenges Christians to “fight” evil, fight the schemes of the Devil, fight injustice, fight sin … “fight the good fight.” What then do you mean by “fight?”

Being nonviolent doesn’t mean you don’t fight. It just says you fight nonviolently. Again, this is why I don’t like the term pacifist. It’s often confused with passive-ness (even though the word doesn’t mean this). You know, letting people break into your house and kill your family.

But the term nonviolence doesn’t refer to one’s posture toward evil but the means by which we confront it. We fight against our enemy with weapons more powerful than tanks or drones. We fight with love, suffering, and, most of all, the gospel.

How successful do you think you will be at helping Christians change their view on warfare and violence? What ultimately do you hope people take away from your book?

Honestly, if someone is so cemented in their presuppositions, I’m not sure I’ll convince them otherwise. But if I can cause people to think, to scratch their head and re-open their Bibles and make an attempt to examine their presuppositions and worldview in light of Scripture, then that alone would be a success in my mind.

But yeah. I’d love to make some converts! But only because I believe that nonviolence honors Christ and cherishes the cross. Ultimately I want more and more Christians to be numbed by the stunning power of a crucified King, a resurrected Lord, who conquered Satan not by using violence—but by absorbing it.

For more conversation on Fight (and to read an excerpt), visit the Patheos Book Club here.

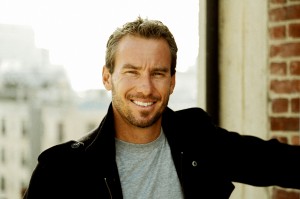

Preston Sprinkle is a professor, speaker, and author. He teaches Bible at Eternity Bible College in Simi Valley, CA, and formerly taught at Cedarville University (OH) and Nottingham University (U.K.). He is the author of several academic books and articles, along with the New York Times bestselling book Erasing Hell, co-authored by Francis Chan. Preston is married to Christine and they together have four children.