Life Together: Claiming Our Story

Exodus 14:19-31

I was at work that morning.

I’d bet almost everybody here has had the same “I remember where I was” thoughts this week, because the 9/11 attacks are one of those experiences about which nobody can help but remember. And because we remember the day, we each have a story to tell—our own version of 9/11.

I was at work, as I mentioned, in the church office, at Saint Charles Avenue Baptist Church inNew Orleans, Louisiana. The church secretary called me into her office because there was something alarming on the radio…something about New York City and a plane crash.

We all huddled in her office around the radio, listening in disbelief. It was unbelievable, you know, because this sort of thing doesn’t happen in our country.

The next few hours and days are a blur, a complete blur. I jumped in the car to pick up my kids at day care, dialed over and over and over again—without success—my friend who worked on one of the top floors of tower one. I sat in stunned silence with my colleagues as we wondered what exactly a religious leader was supposed to do in situations like this. I scoured the collections of sermons and prayers by people like Peter Marshall, who had to preach the week after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, and I helped preside over somber prayer services, hoping what we were saying was the right thing, all the while holding back our own tears as congregation members sat in pews and sobbed with grief and fear.

And just like everybody else, I also sat on the couch and watched the news repeat over and over and over and over until I couldn’t watch anymore. I cried with relief when I heard the sound of my friend’s voice on the telephone, finally—he’d stayed home sick from work that day. And I, yes, even I, went from store to store to store looking for an American flag to hang outside my house. It’s true.

It’s been ten years. Ten years since an event that seems like it happened yesterday, an event that narrates our experience as Americans, that has become such a legendary, life shaking part of all our stories. And we need to tell the story, don’t we? Take a minute and remember with each other: where were you right about now on September 11th, ten years ago?

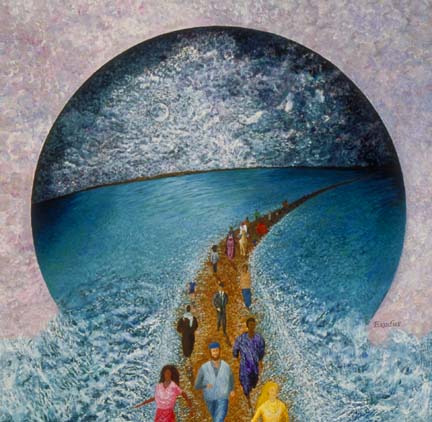

The people of Israel, our ancestors of the faith, also had stories to tell, stories that defined their identity as a people, stories that pulled them together, stories that helped them understand God. The most powerful and compelling story that shaped them, of course, is the story of the Exodus.

That’s what it was called by them years—hundreds of years—after it happened, and that’s what it’s called by us thousands of years since then. And, like most community and faith defining stories, the story of the Exodus quickly took on a life of its own, unfolding in its retelling in all different kinds of versions. In fact, if you read chapters 14 and 15 of Exodus carefully, you’ll find there are three versions—three!—of the same story, right there. Everybody had a different perspective of such a life-changing event. It was one of those, “I remember where I was when…” kind of stories, for sure.

We read part of the story today from Exodus 14. I tried to imagine as I read, how the Israelites might have told the story ten years after they got to the other side of the Red Sea. Can you imagine with me?

Perhaps they sat around a campfire. By then they’d become pretty adept desert-dwellers, nomads who traveled from place to place hoping to find the Promised Land. Some days they felt confident their leader Moses was on the right track. Some days…most days…they felt discouraged. They wondered if God had abandoned them. They began to doubt the Promised Land (whatever that was) even existed at all. They started to think they would live forever as travelers in the desert, that their dreams of settling down and raising their families in one place, of coming into a land they could cultivate and of becoming the great nation God had promised Abram were just pipe dreams.

As we read the Exodus story over the next few weeks we will read of many times discouragement almost got the best of the wandering Israelites. And who can blame them? You have to know, though, that even in their lowest moments they would always—always—stop to remember the Exodus, to tell the story again.

They had to, you see, because there were babies who were born after that day, and young children who couldn’t remember what they’d lived through. And there were the rest of them, who had survived—they’d survived—and they were moving forward into God’s future for their people. In the darkest moments of doubt, they had to tell the story again.

Yes, everyone had a different perspective. And the story unfolded in several different stanzas, depending on who was telling which part. And I’ll bet they gathered on the tenth anniversary of the Exodus, around a fire that cut the chill of the desert night, laying out blankets and gathering their children around, and then someone would begin.

“You know we were slaves inEgypt. Do you know what a slave is, children? Believe me, you don’t want to know! A pharaoh who didn’t know our ancestor Joseph forced us into slave labor. God never left us, though. Even in the hardest, most violent and scary times, we knew God was there.”

Maybe someone else would interrupt: “I don’t know…I have to admit I had my doubts about that. But that’s when Moses arrived on the scene. We were suspicious, of course—he’d grown up in the house of the Pharaoh…but he was really one of us.”

And from another side of the circle: “The angel of the Lord came one night. It about scared us all to death. Moses told us how to protect our families from the plagues, but we knew that we had to escape. Everybody started making plans, packing bags, preparing our children, but we didn’t know when or how it would happen. It was so scary.”

“So we left one night,” another interrupted. “It was hard to move that many people with all of our supplies and animals. We’re much better at it now! We left during the night, hurrying, hurrying, hurrying, trying to get away as fast as we could, hoping Pharaoh would just wash his hands of us, would let us go. But no. It wasn’t long before we could hear the creaking of the chariot wheels and the shouts of the soldiers, and with the sea stretching out there in front of us we knew it was hopeless: we were going to die.”

Another voice echoed loudly: “I, for one, was mad. Sure, I hated being a slave, but seriously? Bring us all the way out here after all of this, only to die?? I tell you, I would never have guessed what was about to happen to us. Never in all of my life.”

“I didn’t know what to think either,” his wife added, “but I don’t expect I’ll ever forget Moses’ words: ‘Don’t be afraid! Stand firm and see the deliverance that the Lord will accomplish for you today! The Lord will fight for you! Just trust!’ Well, it’s not like we had much choice (no offense, Moses) but I don’t think I will ever forget those words. Ever. They gave me courage to just keep moving forward.”

“Oh, I want to tell this part,” said a teenager in the group. “It’s the best part, and my best memory of the whole thing. The night lit up. That’s really the only way I can describe it. There was this big light in front of us, like a moving fire pulling us forward, toward the sea. Behind us we could still hear the Egyptian army, but the fog—the fog and the clouds billowed out like dust behind us and we couldn’t see them. I guess they couldn’t see us, either. My Mom kept pulling my hand and telling me to come on!”

“Yeah, yeah. I remember the fire up ahead, too,” said another, “but I was so scared. The flames of the fire that lit the night sky also reflected on that vast, black sea ahead of us. No way—even those of us who could swim knew there was no way to get our children and our animals, everything we needed, safely to the other side.”

“When we got to the edge of the sea, Moses stretched out his hand over the water. Come on, Moses, stand up and show the kids how you did it! He just put his hand straight out over the water and the water started moving. It started moving with the powerful, rushing sound that huge amounts of water make. The mist of the waves and the smell of the water rolled over us, the fire moved out ahead, the Egyptian army was getting louder and closer, and Moses told us to go…go! Into the water, through the sea, walking!”

“It took a long time. Hours to walk across. I was terrified the whole time. More scared than I had ever, ever been in all of my life. The Egyptians on their chariots were coming behind us, closing the gap—we could still hear them. Their wheels were getting clogged with the mud of the sea bottom, they were just as scared as we were—don’t let anybody tell you different!”

“And then we got to the other side. It was really hard to climb up the banks of the sea, through the sand and mud, to the other side, but what choice did we have?”

“We were exhausted. My children were crying with the cold and the fear, and so was I.”

“And then we turned around to watch the Egyptian army. They were struggling through the pathway in the sea, too. And I, frankly, couldn’t imagine how we’d summon nearly enough energy to keep going. Yeah we were out of the water, but the army was still coming. And they were moving faster than we could ever hope to move.”

“Okay kids! Time for bed!”

“No, they have to hear this part, too.”

“They’ll have nightmares!”

“No, those Egyptians got what they deserved and the children need to hear it. The water started closing in. Big, huge waves tumbled over the whole army. They tried to turn around when they saw what was happening but it was too late.”

“That was the worst part!”

“No, way! That was the best!”

“The way I remember it, you were hiding under one of the carts….”

“I was not!”

“Yes you were, too…!”

“That’s enough. It’s enough to remember. We have to remember. We can never forget. It’s our story.”

I talked earlier this summer in worship about stories. This is what I said: Stories have power…they give us a way to connect with each other using the tool of a shared experience. And the most powerful stories are those that speak to the deepest experiences of human living—the things we have in common even though we are all completely different from each other. In telling and hearing our stories we find connections with each other and connections to truths that are bigger than ourselves. We need to tell the story of faith again and again and again…to remind ourselves that God is well at work in our lives and in our world, and to discover again how we can be part of God’s ongoing work in the world.

That’s why we tell where we were ten years ago. That’s why I feel sure—sure—that ten years after the crossing of theRed Sea, something like the scenario I described certainly, surely happened around the campfires of the Israelites. And it’s why it’s time for us to begin today to tell and to claim our own story—our Calvary story, the story of faith that has been handed down to us for safekeeping, the one we tell over and over, and the one we are tasked with living for the future.

We’re celebrating 150 years as a church next June. Over the course of those years in this place—most of them spent right here in this very building, in fact—a story of God’s faithfulness in hard times has unfolded in many different stanzas. There are, of course, many among us today who could tell many more stories of faith on the corner of H and 8th, NW, than I could, but I’ll begin.

Calvary Baptist Churchwas founded in 1862; the church’s first worship service was held…September 11, 1862. How about that? It was a tense time in our city and in our country, for sure. This church was founded in true Baptist form as the result of a church split over issues related to slavery and abolition. The abolitionists who found this church quickly settled into life in community, building this building and building it again 18 months later after it burned down. It became an integral part of the city’s landscape. The church grew and grew and grew until it was one of the largest in the city, a place where important international leaders and figures of national prominence chose to worship. It became the founding church of important Baptist movements; it was a place where radical social justice stances were taken every decade—every decade—opening doors to all kinds of people who were not really welcomed in other places. This church rode out a changing neighborhood—not just once but many, many times, sticking around to be a place where God was, here in the city.

This is a story that we’ll be telling over the next year of celebrating our 150th anniversary. It’s a story that has become legendary in its telling, all hearts and flowers, no tension or controversy.

As we begin our 150th season and the retelling of this story, of our story, it may do us well to remember other stories that define our lives, to recall how we tend to tell them in different versions as time passes. We need to remember this if we are going to claim our story as a family of faith, because we’re the ones still here. And sometimes living the story here and now doesn’t seem quite as glamorous as retelling the high points around a campfire, does it?

As we begin our 150th season and the retelling of this story, of our story, it may do us well to remember other stories that define our lives, to recall how we tend to tell them in different versions as time passes. We need to remember this if we are going to claim our story as a family of faith, because we’re the ones still here. And sometimes living the story here and now doesn’t seem quite as glamorous as retelling the high points around a campfire, does it?

Telling our memories of 9/11 can easily find us caught in a story that glosses over our own country’s responsibility for violence around the world, the ways in which we have been not just victims but also aggressors. Maybe, in the retelling of the story we’ve tended to highlight one group of victims and forget there were many others who lost their lives, their dignity, their places in American society in the wake of 9/11: in military service overseas, in rescue efforts of all kinds, in trying to live as Muslims in America when fear and prejudice began to punctuate every part of daily life. Nobody really wants to bring that up while telling the story. But if we’re going to claim the story, we must.

And it’s one thing to tell the Exodus story of triumph and victory and just gloss over the hard parts. How, for example, do we make peace with thousands of Pharaoh’s solders, most of whom had no culpability in the situations and absolutely no choice in whether they charged into the sea after the Israelites, exterminated? Is this what we believe about God, that God loves one set of people and doesn’t even think twice about brutally murdering another? Jewish midrash, the rabbis of old, would say that the angels of God rushed to the edges of the Red Sea surrounding the Israelites on the other side and raised their voices to sing a song to triumph…to which God shut them down and said, “How can you sing when my children are lying dead in the sea?” To tell the story, that might not work with your objectives. To claim the story, though, you have to talk about the hard parts, too.

And what about us? A church begun by abolitionists, founding congregation of American Baptist Churches, USA, first white Baptist church to admit an African American member in 1954, central location for respite for those at the Poor People’s March on Washington in 1963, founder of the first ever homeless shelter for women in the city of Washington, DC, committed to stay in a city neighborhood that was quickly turning dangerous and hopeless, calling women into leadership when many others in the denomination would not, opening doors and membership wide to people of all sexual orientations, becoming a model for other urban churches developing strategic partnerships in their cities…ah, the story just sounds so blissful, doesn’t it?

If we tell it that way we forget to include the parts about church conflict, budgetary crises, violent crime, ineffective leadership, hurt feelings and painful words said in anger, commitment that fades, and hopelessness that creeps in from time to time. It’s all part of the story, that hard truths are woven through the wonderful as well.

We can tell our story.

But it’s more powerful to claim our story, the wonderful parts and the hard parts, too. When we claim our stories, you see, we have better perspectives, more courage, a clearer vision to move into the future of all God calls us to be. When we claim our stories, the mistakes and the victories, the good times and the bad, the wonderful and the terrible, we can remember that God stays with us through it all, every single step of the way.

When we claim our stories we can look back over the years and say things like:

“September 11th was terrible in so many ways. And we received in its wake a deeper appreciation for each other, a new awareness of our place in the world, and the strong conviction that we must work for peace as we create a future of justice and hope for all our children.”

Or, we can say things like:

“Thus the Lord saved Israel that day, and the people believed in the Lord.”

Or, we might even say something like”

“At Calvary Baptist Church, we are an ecumenical, multi-racial, multi-ethnic Christian body that reaches out to the world with the Good News of Jesus Christ. To that end we strive to be welcoming, responsive, trusting and prayerful in everything we do.”

Maybe we could. If we have the courage to claim our story. Amen.