There is no society without religion because without religion society cannot exist.

There is no society without religion because without religion society cannot exist.

René Girard, Violence and the Sacred

The science vs. religion debate seems here to stay. Since Darwin published The Origin of Species in 1859, the debate has revolved around which side holds the key to the truth about human origins. Equally contentious is the debate about the cause and cure of violence: is it religion or secularism that holds the key? Are we destined for a battle to the end over religious ideologies or for salvation via the promise of science? If you want to understand our origins and if you care about our present and future survival, science and religion appear to offer two competing paradigms.

The question of origins and of violence are more intimately connected than prevailing theories of either science or religion yet understand. A theory that is currently gaining momentum is one that offers a scientific theory of religion. René Girard’s mimetic theory explains the role of religion in human origins as a solution to the problem of violence. Girard traces human evolution as made possible by evolving discoveries of technologies for controlling violence and establishing peace. In other words, evolving religious technologies.

A Theory of Violence

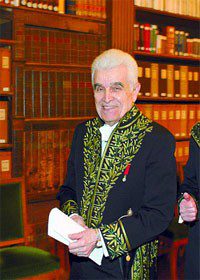

Because Girard’s theory has the same power to transform and enlighten our understanding of the origin of the human species as Darwin’s, he has been dubbed the “new Darwin of the human

sciences” by no less an acclaimed figure than the eminent French philosopher of science and member of the French Academy Michel Serres. This was on the occasion of Girard’s induction into the French Academy in 2005. Like Louis Pasteur, Victor Hugo, Rousseau, Voltaire, Descartes, and Sartre before him, Girard is now an “immortal” – seriously, that’s what they call the Academy members.

Girard’s discovery, and what makes him an immortal, is that you cannot understand human origins and human evolution without a coherent understanding of the adaptive advantage conferred by religion on our species.

Humanity’s Number One Problem

But what adaptive value did religion offer? Girard’s answer is simple: it solved the number one problem facing us at our origins: the escalation of internal conflicts into violence. Mimetic theory claims it wasn’t predation, disease, natural disaster, hunger, thirst or any other extrinsic threat you can imagine that was the greatest threat to our survival. It was our own violence turned against ourselves. In a cruel irony, what made us human also made us more of a threat to ourselves than any other species on earth. Why is that?

Because being human means being hyper-mimetic (mimetic is the Greek word for imitation). In other words, it’s not that monkeys imitate one another and we do not. It’s that we are far better at imitation than our simian cousins. This increase in mimetic ability is what freed us from dependence on instinctual behavior. Rather than being guided by instincts our desires were now guided by each other. Which opened up entire new arenas for conflict!

Girard’s interpretation of the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20) is insightful on this point. After commanding worship of the one God revealed to Abraham, the Mosaic author begins to devise a list of prohibitions, beginning with the most awful things we do to one another – murder. Then he ticks off more crimes in decreasing degrees of severity – adultery, theft, false witness – but appears to realize that if he keeps going on in this vein he won’t really be getting to the root of the problem. So he turns to prohibiting what appears to be the source of all these various bad behaviors – desire of what your neighbor has. As we learn to desire from our neighbor, we will eventually learn to desire something our neighbor has that he would rather not share – like a wife (or husband), a “male or female slave, or ox, or donkey” but again the writer finds himself facing a tediously long list of things the neighbor might possess, so he winds up with the blanket prohibition against desiring “anything that belongs to your neighbor.” When we fail to contain our competitive desires for the things our neighbor teaches us to desire, conflict ensues and violence is “lurking at the door”, as God warned Cain in Genesis 4.

Imitation is what makes learning, innovation and creativity possible. This observation is as old as Aristotle, but Girard realized that thus freed from instinctual patters of desire we were also freed from instinctual braking mechanisms that limited the escalation of our violence. As Girard explains:

We know that animals possess individual braking mechanisms against violence; animals of the same species never fight to the death, but the victor spares the life of the vanquished. Mankind lacks this protection. Our substitute for the biological mechanism of the animals is the collective, cultural mechanism of the surrogate victim. There is no society without religion because without religion society cannot exist. (Violence and the Sacred, 221. Emphasis mine.)

The surrogate victim mechanism is none other than the formula by which sacrificial religions used violence against itself. A small dose of violence directed by the community against a designated, ritually sanctified victim, could discharge all the accumulated conflicts safely before they spread through the community like a destructive contagion.

Religion as a Peace Technology

A ritual sacrifice, properly performed by certified priests, results in a cathartic effect that safely discharges the violence and sets everyone free to go back to cooperating on the hunt or foraging or whatever needed doing. What Girard discovered however is that ritual sacrifice is the background radiation in which we can detect the origin of our species. What he means is that behind the ritual sacrifice of a ritually purified victim was an un-ritualized, spontaneous sacrifice of a randomly chosen victim that brought peace to a community riven by violence. The peace that descended on this proto-human community, not yet protected from its own violence by law or ethics or sacrifice, was just what the doctor ordered. So powerful and unexplained was the appearance of peace in the midst of threatening violence that the victim appeared to be an agent of the divine. As Girard puts it,

The peoples of the world do not invent their gods. They deify their victims. What prevents researchers from discovering this truth is their refusal to grasp the real violence behind the texts (myths) that represent it. The refusal of the real is the number one dogma of our time. It is the prolongation and perpetuation of the original mythic illusion. (I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, 70)

What was ritualized into sacrificial practices at our origins, persists today in what we call scapegoating. Ritual sacrifice and scapegoating are similar phenomenon – in the ancient world their victims became gods. In our world our victims are scapegoats.

Why the shift? Because religion continues to be the science of surviving our own violence. The Judeo-Christian tradition gradually exposed the error at the heart of ancient sacrificial practices: the victims weren’t gods and the gods did not demand victims. From the great discovery of monotheism emerged the discovery of a new violence controlling technology: mercy.

The sacrificial technology followed a homeopathic formula: use a small dose of violence against an expendable victim to prevent a larger, more threatening outbreak of violence from destroying our community. The same element can either destroy or cure – whether it destroys or cures depends on the size of the dose. In contrast, over time the Judeo-Christian tradition developed a formula for prevention that eschews violence altogether in favor of love and mercy, humility and forgiveness. The Gospels, according to Girard, are an undoing of ancient sacrifice by exposing the truth myths are determined to hide: that the victim is neither the cause nor the cure of violence. The victim is innocent and we are guilty, that is we, the ones who sacrifice the innocent victim, are responsible for the violence that threatens us.

It is this discovery, made available to us by the Cross, which has rendered ritual sacrifice obsolete and its modern equivalent, scapegoating, increasingly ineffective. Until we set aside the old failed sacrificial technology and embrace the new technology of mercy we will remain unable to rid our communities of violence and establish a sustainable peace for all people.

An Apocalyptic Choice

Mimetic theory offers the hope of moving beyond the old science vs. religion debate toward a unified understanding of religion and evolution. Without such an understanding, we will not be able to effectively deal with the challenges of the present. As Girard warns us, we must learn to face “the real”. What is real today is that the adaptation that once conferred such a competitive advantage for us, the sacrificial technologies that enabled us to survive our increasing mimeticism, have now become a threat to our survival. The old formula in which violence could cast out violence, has been exposed as an illusion and so its ability to awe and soothe us is rapidly waning. Girard has famously said that the modern problem with violence is apocalyptic because our old technology no longer works and we have not yet fully embraced the alternative. Of the impact of the Christian Gospels, Girard says:

Christ took away humanity’s sacrificial crutches and left us a terrible choice: either believe in violence or not. Christianity is non-belief.

Our future depends on our ability to fully embrace the powerful religious technology that is compassionate mercy, not violent sacrifice. Its adaptive advantage is there for the taking. I’m not sure how optimistic I am about our chances, since Christians ourselves seem unaware of the content of the revelation we have been instructed to share with the nations. We continue to fall into sacrificial behaviors, betraying our mission. Time will tell whether we are worthy of the trust Jesus placed in us. Whatever happens, we can trust that Jesus will be faithful to us. Matthew lets Jesus’ promise serve as the haunting last words of his Gospel: “Remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age.” How the end of the age will come is in our hands.