http://www.michaelolaf.net/maria.html

What impact does grading or rewarding our children for their school work have on their motivation to learn? There’s a wide range of thought on whether or not external rewards motivate kids to do well. But I am a Montessori pre-school directress, and so I am firmly in the camp of those against using external rewards. Here are my reasons.

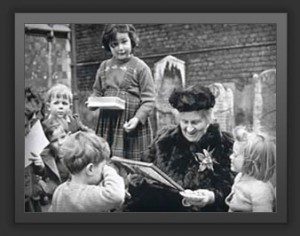

According to Dr. Maria Montessori, children are born with an intrinsic desire to learn. In fact, they love learning so much that the best role adults can play in their lives is to get out of their way. Really! Our job as parents and teachers is to be sure that the environment they are exploring is a safe one, which includes providing a clear set of boundaries and rules for behavior. Once things are safe and clear, the children will naturally engage, explore, wonder, question, and experiment like the little scientists they are until we are more tired of answering their questions than they are of asking them. Young children do not need any external motivation for learning because their internal motivation is so powerful.

In fact, Dr. Montessori observed that offering rewards to children was counter-productive. They actually perceive a star on their drawing or handwriting exercise as an insult. I observed the same thing in my years as a teacher. Because I am a product of the praise and reward system myself, I had to actively suppress my urge to offer rewards. Happily, there are no stars or stickers of any kind in a Montessori teacher’s tool box, but I was brimming with motivational comments. I had to censor things like “Nice job!” or “Excellent work” or they’d come pouring out of me. The kids’ reactions quickly reformed me, however.

http://www.michaelolaf.net/maria.html

The clincher came when one of the children (I taught three, four and five year olds) came over and silently presented his art work for me to see. I was taught in my Montessori teacher training to either accept the offering in silence or if I must comment to make a neutral observation such as, “I see that you used yellow today.” The idea was not to impose my interpretation on the drawing, but to make space for the child to explain the drawing in his own words. Or not say anything at all, if that was his choice. But I just couldn’t help myself. As he held the picture up for my inspection I said quite enthusiastically, “I love it! What a beautiful drawing!” His response was quick and memorable: he looked at me with a mixture of disappointment and disdain and then walked away.

What happened? My reaction had conveyed a message something like this, “I know why you drew that picture – because you wanted to please me. Your desire to draw is really a desire to get me to approve of you, so here it is, my approval.” What I had done was fail to acknowledge his true motivation, which was to draw for the joy of it, the experience and wonder of it. If I could have said, “I see that you used yellow today,” he might have agreed with me or offered his own comment in return which would have taught me so much about who he was as a unique, blossoming individual. But no, I insulted him by acting as if he was an insecure puddle who was as much in need of approval as, well, as I was.

The problem is that for most adults we have had our natural exuberant joy of learning insulted out of us by rewards and grades. What’s taken its place is, sadly, the need to get external signs of approval from others. This negative effect of grades was illustrated in a recent study involving over 11,000 cadets entering West Point. The study explored the effect of “instrumental motives” on successful outcomes. An instrumental motive is when we do something to get a reward, like going to West Point to get a good job later in life. The study contrasted this with an “internal motive” which is doing something for reasons that are inherent in the activity, such as “desiring to be trained as a leader in the Unites States Army.” Guess what they discovered? The “stronger the internal reasons were to attend West Point, the more likely cadets were to graduate and become commissioned officers.”

Of course, attending West Point will most likely get you a better job later in life, but just because “activities can have both internal and instrumental consequences does not mean that the people who thrive in these activities have both internal and instrumental motives.” In fact, structuring your school or business to focus on the instrumental motives turned out be counterproductive by “weakening the internal motives so essential to success.”

Which brings us back to our roles as parents and teachers. What we don’t want to do is weaken our kids’ natural internal motivation to learn. When we offer praise instead of remaining humbly receptive to what the child is offering, we are emphasizing the instrumental over the internal. Repeatedly doing this over time can gradually train the natural love of learning out of our children.