My inner feminist recoils when I hear the term “Son of God.” I get the same feeling when I hear “God the Father.” I mean, isn’t that just patriarchal language that elevates men above women? If so, shouldn’t we do away with such violent patriarchal language about God?

It’s true that each of the Gospels call Jesus “the Son of God,” but here’s the catch: when the Gospels call Jesus the “Son of God” they subvert all forms of violence, including patriarchal structures that treat women as less than men. Here’s how:

The term “Son of God” was frequently used in the ancient world for kings and rulers who were thought to be the full representation of the divine. For example, Pharaohs were thought to be the sons of the great Egyptian god Ra. Many Roman emperors claimed divine sonship. Even King David in Psalm 2 claimed that God said to him, “You are my son; today I have begotten you.” The point is that, in the ancient world, the will of the gods was believed to be revealed through their sons.

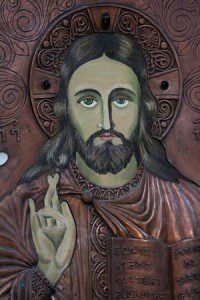

What makes Jesus unique in the ancient world (and in the modern world!) as the “Son of God” is that he wasn’t a violent political ruler like the Pharaohs, Emperors, or even the kings of Israel. They all used violence to maintain their power. Thus, the gods were associated with power and violence. Jesus wasn’t interested in gaining political power through violence. Rather, he confronted the powers of violence and social exclusion with the nonviolent love of the Kingdom of God.

So, when the early Christians called Jesus the “Son of God” they subverted the idea that God is violent. In the Gospel of John, Jesus proclaimed, “The Father and I are one.” Jesus reveals that the Son and the Father are one in their nonviolent love for all of humanity, indeed, all of creation. The Gospel authors essentially asked, “Do you want to know what God is like? Look to Jesus, the true Son of God, who never killed and who invited all people, but especially the outcast and marginalized, into a community of love and embrace.”

Jesus, the Son of God, had a special relationship with the daughters of God in his culture. Women were often treated as less than men in the ancient world. They were frequently excluded from full community and the privileges that men enjoyed. Jesus was formed by significant aspects of Jewish tradition that challenged the patriarchal systems of the ancient world. The Hebrew Bible gives prominent positions to many women. For example, whole books were devoted to Ruth and Esther. Deborah was an important political leader and prophet of Israel. The Queen of Sheba challenged Solomon to work for justice. And the Abrahamic traditions would never have been born were it not for Sarah.

So, from within his Jewish tradition, Jesus subverted the patriarchal systems of the ancient world by including women into his closest community. Women ministered to Jesus (Mark 15:40-41), Jesus talked with women in public (even as his disciples protested – John 4:27), Jesus taught women (Luke 10:39), he was challenged by a woman and subsequently changed his behavior (Mark 7:24-39), he publicly defended a woman accused of adultery by a group of men (John 7:53-8:11), and he entrusted Mary Magdalene to preach the good news of his resurrection to the disciples (John 20:11-18). Jesus, the nonviolent Son of God, subverted the violent patriarchal systems of his day by treating women with equal worth and entrusting them with preaching and teaching the good news.

By proclaiming Jesus as the Son of God, the early followers of Christ subverted violence and patriarchy. They claimed that God is working to transform our violent and patriarchal systems through nonviolent love. In other words, when we talk about the redemption of the world through the Son of God, we are talking about the power of love, mercy, and forgiveness to draw all of humanity into a new community that includes the powerful and the outcasts, the emperors and the widows, the least and the last.

For other parts in this series see:

Who is God? Part 1: God is Love

Who is God? Part 2: The Holy Spirit and judgmental gods not worth believing in

Like Adam Ericksen – Public Theologian on Facebook for more reflections.