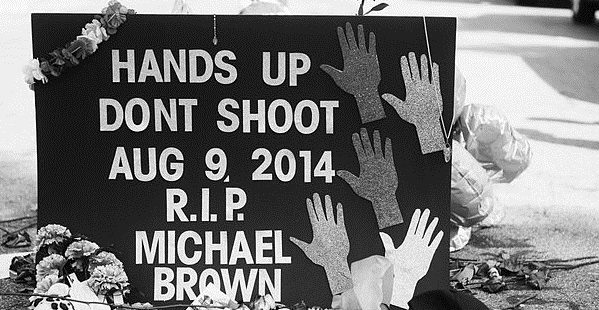

It has been a year since the death of Michael Brown, and seventy years since the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

I am in mourning. I am in rage. I am struggling to plow through with hope and faith in the God of Love who can redeem all of this suffering and senseless murder. I am struggling to live into that hope by learning and shouting the truth and acting upon it.

Michael Brown and the people of Nagasaki are connected by more than just their dates of death. They were murdered by authorities charged to serve and protect. They were sacrificed to a myth of American exceptionalism mingled with a false ideology of white supremacy. Fears were projected onto them. They were dehumanized. Their killings are justified by people who insist that they had to die for others to live.

It is our national faith in sacrifice, in the righteousness of violence, in self-justification and its mirror twin – other-demonization – that most fills me with despair, but also with determination to keep up the struggle to drown out the violence and oppression of the world with rivers of compassion and justice.

Moving forward sometimes feels like swimming through mud, a slow and arduous process, because we are steeped so deeply in a culture, a religion, of violence, overt and insidious. This past year has been a wake-up call to the systemic racial violence on our very own soil, which must be confronted concurrently with the racist, Islamophobic, greed-and-power-driven violence exported overseas. Recognizing the interconnection of these violences, their common roots and the way they feed each other, is essential to the work of rebuilding a new social order on the foundation of love and compassion.

The murders of Michael Brown and the people of Japan were hundreds, even thousands, of years in the making. A single finger pulled a trigger, a single finger pressed a button, but the blood is on an entire world order structured on a profound, but deadly misguided, belief in the salvific power of violence. René Girard teaches us how civilization was founded in murder, as people purged their rivalries over mutual desires by coming together against a scapegoat or enemy, the communal killing of whom produced the cooperation and emotional bonding necessary to form a society. Our own nation was certainly born in the blood of others, as settlers slaughtered Natives and lashes drew the blood of slaves who cultivated the land and became a backbone of the economy. Today, our military and police forces are portrayed by the predominant culture as critical to our safety and survival. Wars and police shootings are deemed necessary, even noble, by the powers that be. Those who “put their lives on the line” to serve and protect are honored and glorified by our culture. Yet the blood of the victims of our state and our military, washing over all of us, does not redeem; it convicts.

Ultimately, these murders can be traced in large part to racism and self-justification, both intimately tied to the scapegoating mechanism. Racism is a type of scapegoating that is deeply embedded in the social structure of the United States. Distinctively American racism can be traced back to the early days of settlement before independence. As Matthew Cooke tells us in this video, natural alliances between African slaves and white indentured servants threatened the elite, who restructured laws to give poor whites slightly more rights and thereby redrew alliances along racial lines. Order was thus enforced not by distributing justice, but by redirecting hostility to a new enemy – the black race – in such a way that preserved slavery, kept wealth in the hands of the few, and placated the poor whites with token privileges. The myth of white supremacy was reinforced by segregation, and it influenced theological interpretation, social science, and even the understanding of biology. Everything about white American culture was set up to portray blacks as inferior, and this myth was believed and passed along as truth. The entrenched racism integral to the foundation of the United States has not been fully uprooted to this day.

The moral pseudo-superiority inherent in racism is a hallmark of scapegoating violence. Righteous self-justification has evolved since the days of slavery and lynchings, but it is still not only a persistent human trait but also very much a part of the American cultural psyche. Overt racism was once considered by some a moral position, to the point where preachers could draw on stereotypes of hypersexualized, bestial black men to incite mobs to murder “righteously” in broad daylight. Now that racism has been exposed as immoral, denial of racial prejudice is necessary to maintain a sense of morality. But the tendency to define one’s self over and against others persists. De facto segregation, a large wealth gap favoring whites, a mass incarceration system disproportionately targeting African Americans, and more, divide the experience of life in America along racial lines, keeping prejudices alive but insidious. Moral superiority felt against those imprisoned, impoverished, or negatively portrayed in the media, often (not always) falls along racial lines.

The concept of superiority encompasses but also transcends race in American culture. “American exceptionalism” is drilled into our cultural consciousness from an early age. Our desire to see ourselves as noble and heroic is nurtured by an understanding of history that portrays the mistakes of the past as long gone, lessons learned. We are a people ever perfecting our union, with liberty and justice for all, we are told. Our self-glorifying culture resists reflection on the systems that enforce order and the order they enforce, at home and abroad. The violence of our military, with bases in over 70 countries, conducting operations both covert and open, is portrayed as a tool for establishing freedom and a “global force for good.”

Racism and pseudo-righteousness cloak murder in the mantle of morality. Centuries of demonization of black males ultimately guided Darren Wilson’s finger on the trigger as he shot Michael Brown multiple times. His irrational fear, that a man already injured was a threat to his life, was deeply conditioned. While he should have been held accountable for his actions, his actions must also be examined in a larger context of the racism that makes the devaluation of black lives a fact of American life. Justification for Darren Wilson’s actions, however, is not just a product of unrecognized racism. It is also the product of faith in the goodness of the system of American law enforcement and American order in general. Officers who enforce order in a nation of liberty and justice for all are good guys; those they kill are bad guys. Thankfully this narrative is being challenged now, but for far too long it went largely unquestioned. The system of policing and law enforcement, while accomplishing good, is designed to uphold an order that is far more corrupt and inherently unjust than we have been conditioned to believe. This order protects the wealthy and hurts the poor and racial minorities in particular. The system can be redesigned, the noble desires to serve and protect can be exercised, but not without extracting the poisons of racism, greed, and resistance to self-reflection.

Faith in the military as a force for good also goes largely unquestioned. The myth of white supremacy is intermingled within foreign policies that seek to manipulate and exploit nations with darker-skinned people and lucrative resources. The myth of heroic violence, reinforced by conditioned belief in American exceptionalism, serves to mask racism, greed, and evil justification of brutality. The comingling of racism with unquestioned self-righteousness manifested itself egregiously in the release of the atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Would this murder of hundreds of thousands of civilians have been justified in the minds of so many without the demonization of the Japanese, who of all the Axis powers were portrayed as the most ruthless and animal-like of enemies? Seventy years later, the lie that such an action was necessary to end the war persists despite evidence that the Japanese were on the verge of surrender before the bombs were dropped. Our reluctance to deal honestly with our historical atrocities enables those atrocities to continue. Death tolls of the war on terror are estimated in the millions. The threat of nuclear annihilation hangs over our heads while we ignore our commitment to disarm and make war all over the world under the pretense of protection, even as military experts (among others) have conceded that our wars have created new enemies, like ISIS, and ultimately make us and those we claim to protect less safe.

Our national order, our world order, is built on the sacrifice of devalued lives. At Raven, we preach mercy, not sacrifice. But in order to have mercy on the victims of our violence at home and abroad, it’s time to make some sacrifices that will alter our self-perception. We must sacrifice the myth of our unshakeable goodness. We must sacrifice our self-justifications. For white Americans particularly, we must sacrifice the denial of our racial prejudices and examine the ways laws and attitudes have continually marginalized black and brown people. The devaluation of black lives has proven deadly and rendered African Americans unsafe in their own nation. For all of us, we must sacrifice our complacency and our distraction that keeps us from seeing the devastation continually being waged in our name. We must sacrifice the myth of righteous violence and truly see the horror of families burying their dead, or fleeing with no time for burials, maimed bodies, birth defects, shattered cities, forfeited futures.

It is terrifying to renounce self-justification and let the truth of our scapegoating violence in all of its forms permeate our consciousness. It is terrifying to allow the notion that evil is not the exclusive property of the “other,” that it resides within our own hearts. But here is the Good News: we are already, infinitely and unconditionally, loved and cherished. We don’t need to define our worth against anyone else. We don’t need to redeem ourselves by finding someone “worse,” perpetuating cycles of violence. Instead, we need to look to the one who became our victim to expose our needless sacrifice of other victims. We need to live into the Love of our Heavenly Father who also loves our victims and our enemies.

What will the world look like when it is structured on all-embracing love rather than the over-and-against violence we see today? It will look like, and be, the Kingdom of God.