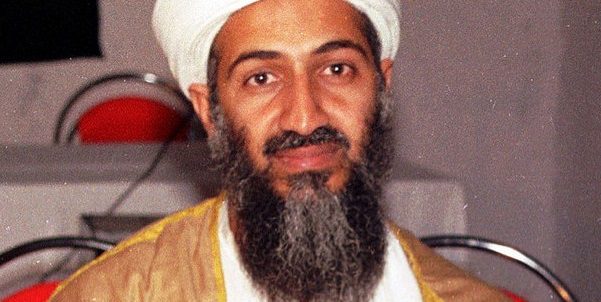

Displayed over a blurred image of Osama bin Laden, the headline on the cover of The New York Times Magazine for October 18 reads: Do we really know the truth about his death? The mysteries of Abbottabad. But weirdly, the article is not an investigation of the truth about bin Laden’s death; it’s an investigation of other investigations. Jonathan Mahler decided to report on two competing narratives about the raid in Abbottabad. His article is a soul-searching reflection on how we can know which version of events is true, or if the truth about our government’s actions can ever be known at all.

As Mahler explains, the White House version of the raid was documented by Mark Bowden in his book, The Finish. In this heroic version, the raid took the Pakistani government by surprise and the SEAL team succeeded against all odds. A more recent counter-narrative by Seymour Hersh (famous for uncovering the My Lai massacre and the abuses at Abu Ghraib) argues that the compound in Abbottabad was maintained by the Pakistani intelligence service. Bin Laden wasn’t hiding at all; he was living in a safe house and our government knew that there would be no attempt to thwart our incursion into Pakistani territory. In sum, Hersh concludes that the “daring raid wasn’t especially daring.”

Mahler traces the differences between the two accounts in expert detail and his article makes a good read. Along the way, he offers a good analysis of the journalist’s challenge, which he describes this way: “Reporters don’t just find facts; they look for narratives. And an appealing narrative can exert a powerful gravitational pull that winds up bending the facts in its direction.” In his concern to avoid generating just one more “narrative” that “bends the facts”, he refuses to take sides. He concludes with this hedge: “It’s not that the truth about bin Laden’s death is unknowable; it’s that we don’t know it.”

Can We Know the Truth?

After reading his article, it’s fair to wonder if we ever will. Mahler himself says that Hersh raised a “disturbing notion” in their conversations: “What if no one’s version could be trusted?” Indeed! If our concern is to learn the facts of the raid, we may easily get lost in a tangle of lies. But that is a truth in itself, a truth of how violence works to destroy the truth. We need to state the obvious here: the subject of all this reporting is a death by violence. Mahler is deceived if he thinks the subject is the truth about the violent death of bin Laden. The subject is violence itself.

There are some things we can know for sure when we encounter narratives of violence:

1. People lie about violence without any moral misgivings about the lying or the violence.

2. People who use violence to achieve their ends never doubt their own goodness.

3. In fact, people who use violence don’t think of themselves as violent people.

4. Perpetrators don’t tell the truth about violence; victims do.

Can We Handle the Truth?

The truth about bin Laden’s death is that it was murder. But the only ones who will call it that are bin Laden himself, his family and friends, and they have all been silenced one way or another. All the other players insist on calling the murder by some other name: justice, revenge, necessary, collateral damage, legal, noble, even good. But victims aren’t fooled by fancy justifications. Their deaths are murder, no matter what their murderers say.

The victims of the 9/11 attacks, if they had not been silenced by death, would have told bin Laden that he was no hero or noble warrior for a worthy cause. That bin Laden refused to hear their accusation of “Murderer!” makes it no less true. Because he refused to accept this basic, most essential fact about that day, we believed him to be violent, cruel, and unworthy of life. If he had not been silenced by death, his accusation of “Murderer!” hurled against us would have fallen on equally deaf ears.

The awful truth about our own violence is that it comes to us from the mouths of those we have condemned to death. It comes from the mouths of criminals and murderers, from warriors for the wrong cause, from patriots for the wrong nation, from believers in the wrong God, from our enemies. If we refuse to hear the truth from bin Laden’s mouth, how can we condemn him? If we refuse to accord him the basic human right to life that he denied others, we have become him. In fact, he has become our mentor as surely as if we had attended an Al Queda training camp and learned to fly a plane but not how to land it.

Squirm and reject this logic if you must, but please don’t pretend we don’t know the truth about bin Laden’s death. It was murder by another name. We are no different than bin Laden, callous murderers all, despite our best efforts to bend the facts against that truth. More disturbing than the notion that no one’s version of violent events can be trusted is that the version that can be trusted belongs to our victims. Bin Laden and his followers reject that notion. Let’s not make the same mistake.