The Taliban. Just the name evokes intense emotions of anger and hatred because, for many in the West, the Taliban is known for one thing: terrorism.

The Taliban. Just the name evokes intense emotions of anger and hatred because, for many in the West, the Taliban is known for one thing: terrorism.

How should Christians react to the Taliban? Sometimes the words of Jesus seem like too much to ask. But sometimes I think they are the only hope for our violent world:

You have heard that it was said, “You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.” But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven. (Matthew 5:43-44)

Jesus calls us to love our enemies in the same way he loved his. But it begs the questions: how can we love the Taliban when they are just so…awful? How can we love terrorists when violence seems to be spreading out of control? Isn’t the “love you enemy” ethic just plain crazy? Or does it provide the only hope for peace and reconciliation?

Making Friends with Crazy

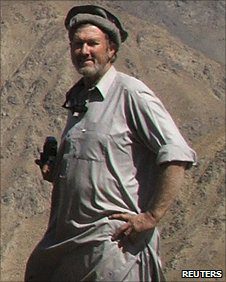

Let’s look to the inspirational example of Dan Terry. His story is told in his biography Making Friends among the Taliban: A Peacemaker’s Journey in Afghanistan, written by Jonathan Larson. Dan was driven by his Christian faith to live in Afghanistan as a peacemaker. You might think that his religious identity would be a deterrent to building peaceful relationships with the Taliban, but that was not the case. “Dan was nothing if not a spiritually rooted and persuaded Christian, but that proved no hindrance to finding his place in a deeply Muslim society.” Far from accusing him of being an evil infidel, high-ranking members of the Taliban became friends with Dan and promised him safety as he journeyed throughout Afghanistan’s backcountry.

Dan’s Afghan friends had two nicknames for him. The first was his Afghan name, Dantri. The second was a bit more colorful: Pagal, which means Crazy. Indeed, “Sometimes people thought Dan was slightly unhinged, because he insisted on the good in all people, often in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary.”

Dan had intuited something incredibly important about human nature. When it comes to violence and peace, humans are mimetic. Without realizing it, we instinctively imitate the violence against us, but we also instinctively imitate peaceful actions. Dan’s story reveals the mimetic aspect of human nature and the power of love to transform violence. Once a visiting minister asked Dan how Christians should pray for the Afghan people. Dan responded, “What I can tell you is this. It must be with great love. Above all, we must love them.”

An Unlikely Love

It was that radical love that made Dan friends with nearly everyone he met – even those who sought to persecute him. He was frequently captured by Taliban commanders, yet Larson writes that Dan was convinced “it was possible to conduct reasonable discussions … with the Taliban when differences or difficulties arose.” Dan was once captured while traveling in the Afghan backcountry. The hostile commander who captured him thought he could extort money from him; but Dan had nothing to give. As the hours passed, Dan remained calm and friendly to his captor. Soon, his captor imitated Dan’s peaceful spirit. “They ate together and drank tea as conversation and camaraderie flowered. In time, it dawned on the captor that a strange friendship had sprung between him and his oddly warm hostage.”

Dan’s strange friendship with the Taliban continued to grow. He never carried a weapon to protect himself. He relied on love, kindness, and friendship. Dan “counted among his friends the Taliban commanders of his neighborhood, insisting that they were not the caricatures of evil portrayed in the West. Flint-like in his belief that there was something noble in each neighbor, Dan kept reaching for the humanity of each person he met.”

More Muslim than we Muslims?

One Afghan stated, “Dantri was more Afghan than we Afghans, and he was more Muslim than we Muslims.” According to this man, Dan was more Afghan than them because of his trustworthiness, loyalty, and sacred hospitality. What made him more Muslim? His Afghan friends claimed, “In the greatest commandments of our scripture–to practice humility; to be generous to widows, the orphans, and the poor; and to be selfless and persevering in the search for justice and peace–Dantri was more Muslim than we Muslims.” The mimetic aspect is obvious; Dan and his Muslim friends inspired and modeled for one another how to become more caring and compassionate. In the words of the Quran, “Good and evil cannot be equal; repel what is evil with what is better and your enemy will become as close as an old and valued friend.” (41:34)

Tragedy

After 30 years of working in Afghanistan, Dan tragically was killed along with a group of other humanitarian workers. They were ambushed and executed by 10 gunmen while delivering medical supplies to villages. Though there were investigations, the murders remain a mystery. The most prominent theory claims that the perpetrators likely were Pakistanis who didn’t know Dan. What we do know is that the Afghan Taliban, who we in the West think are quick to take responsibility for any act of terror, vehemently condemn the murder of their friend and deny any responsibility for the attack.

Still, Dan’s death could make us skeptical about his pursuit of friendship with the Taliban. We may accuse him of being foolish. Indeed, Dan’s life was filled with risk, but the alternative of war in Afghanistan has also been risky, and has only ensured a mimetic cycle of violence along with deeper enmity and distrust between our two nations.

Overcoming Stereotypes

Dan’s strange friendship among the Taliban gives me hope for humanity. Dan believed that the West and the Taliban have distorted images of each other that can only be reconciled through the pursuit of love and friendship. “If that is true,” writes Larson, “then the Taliban and Western societies, as well as diplomats, will need to surmount the caricatures that have been imprinted on the public mind–those cartoon-like distortions of each other that have served the cause of war but that now thwart any path toward lasting peace.”

Dan’s life was based on the crazy, infectious love that Jesus taught. After meeting Dan, some war-weary Afghans in the central highlands responded mimetically to Dan’s peaceful spirit by forming a society called the Hezb-i-Pagal: the Party of Crazies. “The sole condition of membership is a ‘mad’ pledge to seek the good of the community and to disavow fighting and corruption.” Today, the Hezb-i-Pagal is headquartered in a village just west of Kabul. The requirement for membership is to help construct community buildings, including schools, clinics and mosques.

Dan’s story is inspiring, but I’ll be honest, I’m not going to Afghanistan to befriend the Taliban any time soon. Sometimes we can think less of ourselves by comparing our lives to people like Dan. But that’s not the point. Rather, Dan is a model for all of us. His devotion to radical Christian love and commitment to friendship and reconciliation is an important example that can be practiced in our families, neighborhoods, work environment, and religious institutions. The love Dan showed is risky, but it is our hope for a more peaceful world.