What’s the difference between a beheading and a crucifixion? I ask the question as a Christian because we profess that a method of execution every bit as shocking, and perhaps even more cruel, than the beheader’s axe is the vehicle of our salvation. If we do not reflect upon the difference (and the disturbing similarities) between our veneration of the cross and the state support of the beheader’s axe by the self-declared Islamic State in the Levant (ISIL) then we will not find a way to respond to the provocation from ISIL that does not betray our savior.

What’s the difference between a beheading and a crucifixion? I ask the question as a Christian because we profess that a method of execution every bit as shocking, and perhaps even more cruel, than the beheader’s axe is the vehicle of our salvation. If we do not reflect upon the difference (and the disturbing similarities) between our veneration of the cross and the state support of the beheader’s axe by the self-declared Islamic State in the Levant (ISIL) then we will not find a way to respond to the provocation from ISIL that does not betray our savior.

Should US Christians Support Military Action Against ISIL?

Our horror at these executions is in stark contrast to the cool, unfeeling attitude of ISIL. We can see all too clearly what they cannot, that their victims are innocent and do not deserve to be killed, let alone in such a gruesome way. And we are keenly sensitive to the suffering of the victims’ families who are doubly victimized by the public display of their loved ones’ violent deaths. Why is ISIL blind to what we can see? Are they so inhuman, so outside the pale of normal human emotions that they are the ones who do not deserve to live? Isn’t it a good and right use of the US military to seek out destroy such terrorists, such inhuman humans? Should we, the good citizens of the good nation, become their executioners?

Many US Christians answer yes to this question, and they do so in good conscience. The death of our savior on the Cross is the very thing that has sensitized us to the plight of victims and demonstrated what the Hebrew prophets had been proclaiming with very little success: that the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob is a God who hears the cries of the innocent, the oppressed, the widows and orphans. ISIL’s rigid enforcement of their cruel brand of Sharia in Syria and Iraq has generated a wail of suffering that has surely reached God’s ears. Christians confess that the God of our ancestors is a God who desires not empty sacrifices or mindless obedience to the law, but who longs for mercy, for justice, for humility and love. When the Kings of Israel and Judah and the Priests serving in God’s Temple turned away from God’s will in these things, the entire nation suffered under God’s judgment. What better use of government authority and might, what would be more in keeping with service to our God, than to use whatever power we have to defend victims of oppression and violence?

Whose Side is God On?

Indeed, this is a compelling argument. It holds immense appeal precisely because it feels so right. It situates us on God’s side, as good people executing God’s will, but the difficult truth is that ISIL is compelled by the same argument. Their express aim is to inaugurate an era of God’s peace and justice by restoring God’s rule on earth, what is known in Islam as the Caliphate. Their belief that their goal is so noble, so in keeping with God’s will for peace, that any means is justified to achieve their end. Including the beheading, imprisoning, and punishment of their enemies – God’s enemies – whether infidel or Muslim. Isn’t that our argument, too?

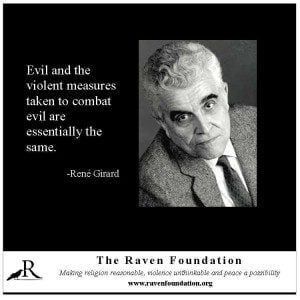

So what makes us right and them so wrong? One reason I have heard offered in mimetic theory circles is that Islam is a mythological religion perpetuating pagan beliefs rather than revealing anything true about God. Such a claim is made in the context of mimetic theory’s understanding of the role of myth in human culture, which runs counter to popular conceptions. Myth is often praised for its poetic beauty or as a window into the complex realities of the human psyche. While these observations may be true, according to mimetic theory they entirely miss the salient point. To summarize all too briefly, mimetic theory holds that myth hides the truth of human violence and instead perpetrates the mistaken belief that violence is sacred. Myths tell stories in which the enemies of the community who are causing all the trouble, mayhem, conflict, and natural disasters must be expelled or killed for peace and harmony to be restored. Because these trouble makers are both the cause of the crisis and the cure when they are expelled, the mythological mind sees them as divine beings, gods who are capable of harm as well as good. To call Islam a religion of myth is to call it a religion of violence and to accuse it of perpetuating this ambivalence about God’s nature. It’s a damning accusation made in sharp contrast to the parallel claim in mimetic theory that Christianity is the religion that exposed the lie of the mythological world by revealing that God is not fickle or ambivalent. The Christian God is a God without any violence at all; violence belongs to humans and God longs for us to leave it behind as a failed instrument of peace to embrace love and forgiveness instead.

God Grieves All Violence

I believe that this use of mimetic theory to condemn Islam is denounced by the theory itself. Mimetic theory does not condemn Islam as an archaic religion but rather condemns the practice of demonizing others for their violence while justifying our own. This sin is not exclusive to Muslims or to Christians; all of us are guilty at one time or another of believing that our own violence is necessary and good, justified by our noble ends and blessed by God. I embrace mimetic theory for its insight that no divine agency is required to understand the phenomenon of violence – violence belongs entirely to the domain of human beings. Mimetic theory critiques all explanations of God’s involvement with human affairs that deny human culpability for violence, whether Christian or Islamic.

Christian theologians using mimetic theory have shown me that God entered into the history of human violence at the Cross not to endorse violence but to discredit it once and for all. When Christians buy into theories that say that God required his son’s death for our salvation, they are falling victim to mythological thinking. They are no better than ISIL, which betrays its own religion’s insistence on mercy as God’s unique and defining characteristic. (For a deeper discussion of the nonviolent resources in Islam, see my Raven colleague Lindsey Paris-Lopez’s recent article, Thirteen Years of Interfaith Reconciliation: 9/11 Then and Now.)

When Christians seek to destroy ISIL for their use of violence, we fail to see that the Cross and the beheader’s axe reveal the same thing: God does not require the deaths of any victims, including his own Son; God grieves all such deaths. By allowing himself to be killed by agents of government and religious righteousness, God intended to send a clear message that “when you kill your enemy, no matter how convinced you are that you are doing my will, you are killing an innocent victim, one of my beloved children.” The message of the Cross is that peace will not come by way of violence. Look at our own reaction to the beheadings – have we responded with mercy and peace or have we been incited to murderous rage? The latter, of course.

By seeking to purify our world of ISIL, we are of the same mind with them as they seek to purify their world by violent means. We each define and defend our communities by whom we exclude and are willing to kill without remorse. This is “violent atonement”, a mythological way of thinking and the source of the eternal return of myth in which life repeats itself in endless, identical cycles never heading anywhere, devoid of hope. Those who hope for peace and who claim to follow the Prince of Peace must abandon our mythological belief that God approved of and required the violence at the Cross. Instead, we need to accept that the violence at the Cross was as abhorrent to God as the violence of ISIL beheadings and, an even more scandalous claim, the violence at the Cross was as abhorrent to God as the violence we commit against ISIL. Only then will we see that from the Cross, as a victim of human violence, God forgave us. Only then will we understand the radical mission that the risen and forgiving Christ entrusted to us – the ministry of reconciliation of all people. The only way out of the eternal, futile return of violence for violence is through the way of God’s “nonviolent atonement”: only inclusive, all-embracing, endlessly forgiving love returned for violence can transform individuals and the world. Christians will not be worthy of the name until we believe as strongly in the power of love as our Savior did from the Cross.

For a further exploration of the difference between myth and Scripture, see the study guide, Romulus & Remus Meet Cain & Abel. For use in small groups, it is available here in the Patheos Premium store. Other study guides from Teaching Nonviolent Atonement for adult and youth groups are available here. Coming soon, a live video chat exploring mimetic theory and Islam with Adam Ericksen and Lindsey Paris-Lopez. The chat information will be posted on the Raven Foundation Facebook page.