JOHN QUINCY ADAMS

In every portrait taken at every age, his eyes just snap with intelligence. To look at John Quincy Adams is to acquaint oneself with lightening held barely in check.

He was not a man in love with the idea of being loved. He abhorred small talk and trends. Although a gifted linguist who served successfully as a foreign diplomat, it was his pragmatism more than his populism that garnered respect. Perhaps that preference would be valuable to the nation in 21st century American politics.

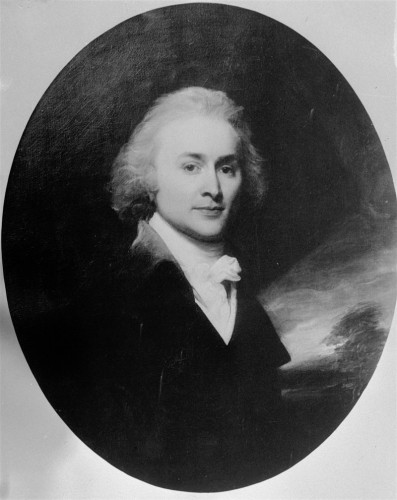

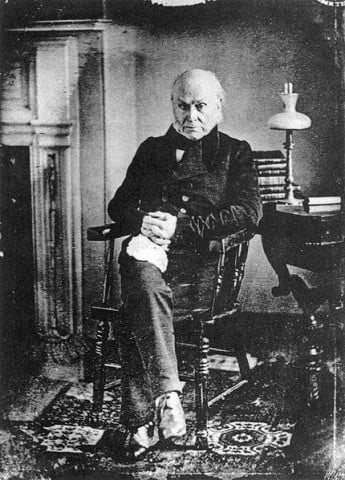

In John Singleton Copley’s portrait Adams is undeniably handsome but the young man in we see here – who graduated from Harvard College in two short years – seems anxious to break the pose and move on; you can envision him walking through the frame, exit, stage right, to get on with more important matters. In this he reminds me of Bobby Kennedy. Sitting for this daguerrotype (earliest photography) shortly before his death, the eyes still snap; the man seems disinterested in mere fripperies.

As a boy he watched the Battle of Bunker Hill with his mother, at a discreet distance from the fighting. Like his father he never owned a slave and never liked slavery. He loved free speech, both in concept and in practice. He skinny-dipped in the Potomac. For all his diplomatic skills, he was never one to glad-hand. An all-night pizza-and-bull session – had pizza been available in his day – would have held no allure. Attempting to explain his disinterest in crowd-pleasing he wrote, “I have no powers of acclimation.” He acknowledged that some called him a “gloomy misanthrope.”

Adams got the presidency on a technicality and wrote of the office: “I can scarcely conceive a more harassing, teasing, wearying condition of existence.” If the foibles and nattering ankle biters were that annoying 200 years ago, imagine him being president in the day of internets, blogs, “netroots”, “wingnuts” and 24-hour-always-hungry news networks.

Perhaps it is the technology of the age that has brought affability and a gift for hucksterism to the fore in politics, and rendered them supremely consequential. I wonder how the giants who formed our nation would fare, these days, hunkering down with Chris Matthews and Barbara Walters. Would Ben Franklin’s genius be undermined or enhanced by insta-media? Would John Adams be considered too crotchety, like Bob Dole? Would George Washington be considered too staid? Would Thomas Jefferson have to endure the wrath of Keith Olbermann for daring to play his violin while something was left unresolved in the nation? Would any of them get elected under the intense scrutiny of our age, wherein – as Don Surber notes here – so many are so easily scandalized?

Failing at his bid for re-election, Adams went home to Massachusetts for just a year, then went back to congress – where he stayed for another 17 years – a powerhouse nicknamed “Old Man Eloquence.” He died at age 80 saying, “This is the end of earth; I am content.”

I look at John Quincy and think, “I’d like to talk to you, to make your acquaintance, to know what you thought about things, then…what you’d think of things, now.”

To which he would probably reply, with brow barking, “stop daydreaming, girl, and do something sensible!” I need to read a good biography of the man.