“There are two forms of excess; to exclude reason and to admit nothing but reason.”

– Blaise Pascal

“I know the plans I have for you,” says the Lord. “Plans of fullness, not of harm. To give you a future, and a hope.”

– Jeremiah 29:11

“Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof.”

– Matthew 6:34

A couple of years ago, in pondering the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, I wrote:

If one goes back to the first lines of Genesis and to the first lines of John’s Gospel we see the same images – emptiness, a Word, movement. It is natural to think that Christ’s birth is a reflection of the whole “big bang” of Creation; the first one made the world and everything in it, the second returned it to its origins, wedded in covenant. (I am one of those Christians completely comfortable with the idea that the Creation story in Genesis is simply another way of explaining our connections to stardust).

The ultra-simplistic secular conventional wisdom-built by straw-men-loving politicians and those helpers in the press who have no difficulty distorting positions in order to sustain a narrative-is that “Christians hate science.”

This is untrue, of course. That bigoted meme is simply a handy stick meant to cower into silence those who would question an ideological crisis de jour/cause célèbre. I wonder how many people who accept the narrative realize that the inventor of the microscope was a Dutch Reformed Christian?

The Creationism/Intelligent Design vs Evolutionism debate-often reduced to a few snorting soundbites caricaturing “the other side’s” position (whatever side or position that may be)-is a politicized mess, but despite a few stone-skips in the water of history (and a general mutual wariness that has to do with what might be called “issues of eminent domain”) science and faith have managed to co-exist and even co-operate, because they are both in the business of mystery and wonder. And, as we hear from St. Gregory of Nyssa, “…only wonder leads to knowing.”

When scientists and the religiously-inclined are seriously committed to serving wonder in good faith, there is often tremendous synergy; it has not been unusual for scientists and mathematicians to hold deep religious beliefs. Gregor Mendel, the so-called “Father of Genetic Sciences” was an Augustinian monk. Georges Lemaître, another priest, applied Einstein’s Theory of Relativity to Cosmology. Theodosius Dobzhansky (evolutionary synthesis) was a Russian Orthodox communicant. Blaise Pascal was a physicist whose religious writings never fail to stir (and are put to very good use in Piers Paul Read’s terrific book of essays, Hell; and Other Destinations). Francis S. Collins, recently selected by President Barack Obama to head the National Institute of Health is one modern scientist whose work slowly brought him to faith, and there are many others who have found (from Deism to full-on doctrinal observance) through the strict confines their scientific method.

The engagement between science and faith may be analogous to Greco-Roman wrestling; two very strong entities grapple, resist, hold, and release but remain mostly bound in an intricate dance that is both unsettling and beautiful. Similarly matched in strength, both straddling the same foundation of awestruck inquiry, the “victor” in one match can easily be the vanquished in the next.

All of this makes Andrew Parker’s The Genesis Enigma: Why the Bible Is Scientifically Accurate, of keen interest to those following the debate on our beginnings. A synopsis from a piece in The UK Daily Mail sounds enticing:

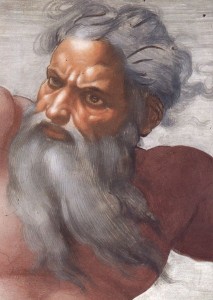

The revalation [sic] came to Professor Andrew Parker during a visit to Rome. He was in the Sistine Chapel, gazing up at Michelangelo’s awesome ceiling paintings, when a realization struck him with dizzying force.

‘A Biblical enigma exists that is on the one hand so cryptic it has remained camouflaged for millennia, and on the other so obvious one cannot miss it.’

The enigma is that the order of Creation as described in the Book of Genesis, and so powerfully depicted in the Sistine Chapel by the greatest artist of the Renaissance, has been precisely, eerily confirmed by modern evolutionary science.

Parker’s thinking is fascinating as it breaks new ground:

On the fourth day, Genesis famously becomes confusing. On the first day, remember, God has already created light, and made Day and Night. But it isn’t until day four that he makes the lights in heaven, the greater light to rule the day and the lesser the night.

Hang on – so he made ‘Day’ three days before he made the Sun? … Yet the writers of Genesis were just as well aware as us, surely, that the sunrise causes the day. You don’t need a degree in astronomy to work that one out. What on earth did they mean?

Here, The Genesis Enigma comes up with a stunningly ingenious answer. For Parker argues that day four refers to the evolution of vision. Until the first creatures on earth evolved eyes, in a sense, the sun and moon didn’t exist. There was no creature on earth to see them, nor the light they cast.

When Genesis says: ‘Let there be lights… To divide the day from the night,’ it is talking about eyes. ‘The very first eye on earth effectively turned on the lights for animal behaviour,’ writes Professor Parker, ‘and consequently for further rapid evolution.’

Emphasis mine. Intriguing, no?

Created creatures continually evolve; from conception to death, life is an evolutionary proposition which argues for itself with every new insight, and that makes a grave case against unnatural endings, for as each age perceives scientific advances as happening with alacrity, our understanding unfolds slowly, imperceptibly, amid living, progressing humanity.

“Let there be light.” Then there is fire. Then there is the wheel. Then there is a canoe, then there is a coach. Then their are great buildings, monuments and designs as humanity dreams and tinkers. Leonardo studies birds and flight, fish and underwater travel; Benjamin Franklin creates primitive flippers and flies kites in the rain, and before and after them humans direct the Divine Spark within toward things as mundane as wire hangers and as fantastic as a laser. In failure or success, they evolve; enigmata unfold before them, and with them, toward…what, exactly?

From the mind of Michelangelo comes staggering vision applied one paint stroke at a time, and as he dabs at the stone, even he cannot dream that 600 years later, in a world where mankind considers walking on the moon to be “old stuff,” a scientist will ponder this work and discover within it another clue – another way of applying all we do know to that which we do not understand – thus angling Adam’s outstretched, tentative hand just the tiniest bit nearer to God’s.

“‘I know the plans I have for you,’ says the Lord.” Millennia later, there was a train, then a car, then a plane. Then there was a spacecraft landing on a distant moon where, unbeknownst to billions, an astronaut -launched into space on a giant fireball of science- “…gave thanks for the intelligence and spirit that had brought two young pilots to the Sea of Tranquility,” using the primitive and eternal elements of Holy Communion.

The outreach continues, and so does the unfathomable evolutionary journey of matter, mind and Maker. The psalmist tells us “our span is seventy years, eighty for the strong… no more than a watch in the night,” in the sight of God. And each life, concentrating on what it sees and what it knows (and what it suspects) cannot begin to imagine how the goods and evils brought forth in day may further God’s purpose. Each step forward or backward on the trail of human wisdom is sufficient unto its time; we are on an evolutionary crawl to the next era and the next revelation-and then the next-in accordance with a plan.

What an invitation to Trust. And with that trust, what could Christians possibly fear from science?

Related: Stargazing with Merton and Rambling Along

Annie Gottlieb is in love with Hubbel, and also muses on the split between religion and science. Great posts.