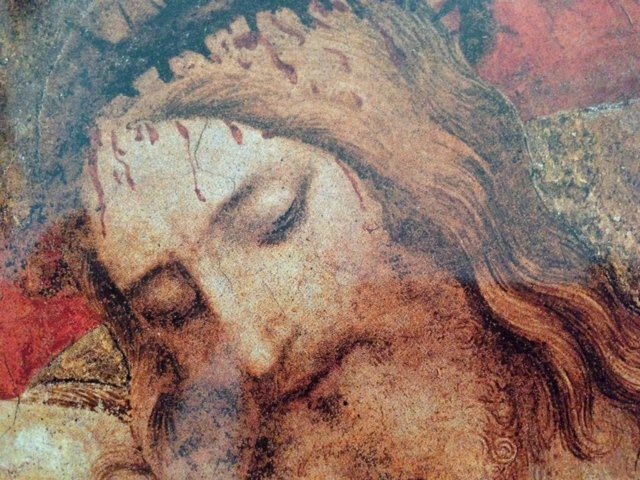

On the Cross, God’s eros for us is made manifest. Eros is indeed – as Pseudo-Dionysius expresses it – that force “that does not allow the lover to remain in himself but moves him to become one with the beloved” (“De divinis nominibus”, IV, 13: PG 3, 712). Is there more “mad eros” (N. Cabasilas, “Vita in Cristo”, 648) than that which led the Son of God to make Himself one with us even to the point of suffering as His own the consequences of our offences?

Dear brothers and sisters, let us look at Christ pierced in the Cross! He is the unsurpassing revelation of God’s love, a love in which eros and agape, far from being opposed, enlighten each other.

On the Cross, it is God Himself who begs the love of His creature: He is thirsty for the love of every one of us.

— Pope Benedict XVI, Lent 2007 “Love Letter”

Most modern biblical translations give us the final words of Christ as “It is finished.”

Encountering the Douay-Rheims translation a few years ago, I read “It is consummated.” And my understanding of the crucifixion of Christ, of the whole meaning of the God-man as Bridegroom and the church as Bride began to expand. Back then, I had not yet encountered Pope Benedict’s stunning thoughts on the “mad Eros of the cross” but discovering “consummated” over “finished” was equally as instructive.

Knowing nothing of Greek, still “consummated” seems to me to be the more theologically complete translation, but I can understand how — encountering that “mad eros” of the cross — some people might feel more comfortable with the word “finished.” There is mystery enough to that word, and it doesn’t intrude on our more fastidious sensibilities; it doesn’t make us uncomfortable by linking what we think of as a baser nature that too often leads us to sin, downfall and exploitation, to such a salvific act of love.

And yet, every covenant between God and humanity has been a blood covenant; back in the day — before we began to think of both hymens and babies as “bits of tissue — marriages and births were blood covenants, too, all of-a-piece and connected to an understanding of God-with-us; eternal Emmanu-el; present of every part of our lives.**

The constant encounter between God’s ever-present “yes” — upon which all of creation is formed and is still expanding — and the brokenness of humanity which constantly tempts us to “no” demands the inclusion of eros. It demands, finally, an understanding that God meant to woo us and to have us, to be one with us, all along — as spouse and companion — but always, necessarily with our consent.

I actually wrote about this in Strange Gods, and yes, the imagery made some people uncomfortable, but I believe it is a key to the deepest mystery of ourselves as free beings:

Look at the profundity of God’s love for his people, Israel, and for those of us grafted onto that branch. He gives his people something better than a king—something transcendent and eternal and incorruptible. But because they are so body bound, so captive to their senses to touch, hear, taste, and smell, they cannot see what he shows, which is everything. And so they whine, “Well, we want a king like they have over there,” and God, staggeringly, acquiesces.

God takes pity on human limitations and tries another way of teaching and reaching, a better way to know the transcendence. He says, in essence:

My love and my law are not enough? You need a corporeal king? All right then, I will come down and be your corporeal king. I will teach you what I know—that love serves, and that a king is a servant—and I will teach you how to be a servant in order to share in my kingship. In this way, we shall be one—as a husband and wife are one—as nearly as this may be possible between what is whole and holy and what is broken. For your sake, I will become broken, too, but in a way meant to render you more whole and holy, so that our love may be mutual, complete, constantly renewed, and alive. I love you so much that I will incarnate and surrender myself to you. I will enter into you (stubborn, faulty, incomplete you, adored you, the you that can never fully know me or love me back), and I will give you my whole body. I will give you all of myself unto my very blood, and then it will finally be consummated between us, and you will understand that I have been not just your God but also your lover, your espoused, your bridegroom. Come to me, and let me love you. Be my bride; accept your bridegroom and let the scent and sense of our love course over and through the whole world through the church I beget to you. I am your God; you are my people. I am your bridegroom; you are my bride. This is the great love story, the great intercourse, the great espousal, and you cannot imagine where I mean to take you, if you will only be faithful . . . as I am always faithful, because I am unchanging truth and constant love.

This God of Abraham, this king, this one who ravishes will give us anything, if we only are willing to trust the truth, even though we do not understand—have not understood since humanity first showed its instinct to hide from God, and will never fully understand—what it is his love has in mind for us, which is simply, “Olly, olly, oxen free; in my light, in my love, you need not hide.”

Christ’s death at Calvary, which Deacon Greg writes of so movingly here, is a consummation meant to set us free, to bring us forever out of the shadows and “into his marvelous light”, wherein love may not be hidden, nor distorted, nor perverted, if only we allow our own “yes” to ride upon the Creator’s.

And this intercourse does not end with the passing of Easter. As Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry wrote of the Holy Eucharist:

There is something carnal, intimate, almost sexual even, to this idea of touching and tasting God. It’s a reminder that God is not so much to be understood (indeed, He can’t be) as to be experienced. The Eucharist also asserts that spiritual realities, rather than visible realities, are the only true realities — the same belief that sends martyrs singing to their execution.

In his book, Holy Sex, Dr. Gregory Popčak affirms all of this:

Unlike other references to the relation of Christ to the Church, such as Shepherd to sheep, King to subjects, and so on, the Bridegroom-to-Bride reference is primary and non-figurative. It is not a metaphor, but a literal statement that Jesus’ love for us is marital. It is, of course, not sexual, not reproductive in a physical way.

Physical reproduction would be too easy. Christ means for us to empty ourselves to him and then to each other, as completely as he has emptied himself on the Cross.

It is the challenge of a whole lifetime. And if taken up in good faith, it leads (even amid our failures) to an empty tomb, and life eternal. Because death becomes destroyed.

**This understanding is one reason why, logically, the Sacrament of Marriage cannot simply be walked away from anymore than we may walk away from our children. But that’s for another day.

Comments are still closed.

This piece was originally posted in April of 2014