The Buddha said:

“Right speech, right action, and right livelihood – these states are included in the aggregate of virtue. Right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration – these states are included in the aggregate of concentration. Right view and right intention – these states are included in the aggregate of wisdom” (MN 44 Bodhi).

There is a Buddhism for just about anyone. Some are interested in going to heaven. The Buddha taught how to do that. Some are interested in inner peace and a less stressful life. The Buddha taught how to gain that. And some people are interested in escaping the prison of Samsara. And guess what? The Buddha taught how to attain nirvana and escape the cycle of rebirth.

The Three Levels

In our passage above we see that the Noble Eightfold Path is divided into what is called the three trainings. They are “virtue” (Pali, sila) which I prefer to translate as morality, “concentration” (Pali, samadhi) which I prefer to translate as meditation, and “wisdom” (Pali, panna).

The Noble Eightfold Path includes “right view, right motivation, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right meditation” (MN 44 Forrest). It is interesting to notice that the order of the three trainings is different. In the three trainings, the Noble Eightfold Path is rearranged to this order: “right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, right meditation, right view, and right motivation. Why?

The three trainings rearrange the order of the Noble Eightfold Path because the Path is like a wheel, not a straight line. Once you have begun the three trainings, it means that you already have an element of right view and right motivation. Now the aim is to purify and mature your view and motivation through the practice of morality and meditation. So the order given in the standard list of the Noble Eightfold Path is for outsiders, once you commit to training in the Buddha’s doctrine and discipline you follow the order of the three trainings.

So let’s return to the three trainings of morality, meditation, and wisdom. What is interesting is that each of these trainings speaks to different people who may have different aspirations in their pursuit of the Dharma. For example, for those who are concerned about a better rebirth or about going to heaven, the training in morality addresses that. For those interested in peace of mind and happiness in this life, the training in meditation addresses that. And for those who want ultimate release from this whole wheel of existence, the training in wisdom promises nirvana, ultimate liberation.

Here I might mention in passing just how skillful the Buddha was as a teacher. “It is true that the term translated ‘skill in means’, upaya-kausalya , is post-canonical,” writes Richard F. Gombrich, “but the exercise of skill to which it refers, the ability to adapt one’s message to the audience, is of enormous importance in the Pali Canon” (17). This is seen in the three trainings. Some people are interested in going to heaven, some are interested in finding inner peace, while others are after ultimate liberation. The Buddha’s message applies to all three.

Level One: Morality for Heaven

The Buddha said:

“The first assurance he has won is this: ‘If there is another world, and if there is the fruit and result of good and bad deeds, it is possible that with the breakup of the body, after death, I will be reborn in a good destination, in a heavenly world’” (AN 3.65 Bodhi).

In this passage, the Buddha is passing through the village of Kesaputta and meets with a clan known as the Kalamas. They were “perplexed and in doubt” about all the different teachings that abounded in India at the time. In the process of helping them discern truth from error, he teaches them about the “four assurances in this very life” (AN 3.65 Bodhi).

He addressed them with, “If there is another world,” not because he was in doubt about it. As the Buddha said elsewhere, “Since there actually is another world, one who holds the view ‘there is no other world’ has wrong view” (MN 60 Bodhi). But he is meeting them where they are.

This is where Buddhism has common ground with almost all other religions. As the apostle Paul asks, “do you not know that wrongdoers will not inherit the kingdom of God?” (1 Cor. 6:9 NIV). He even taught a version of the law of karma, “A man reaps what he sows” (Gal 6:7 NIV). The Quran warns, “Think not that ALLAH doth not heed the deeds of those who do wrong” (14:42.43).

Do all good people go to heaven? The apostle Peter said, “I now realize how true it is that God does not show favoritism but accepts from every nation the one who fears him and does what is right” (Acts 10:34-35 NIV). Even though some passages in the Bible appear to disagree with Peter. Abraham addressed the God of Israel, saying, “Far be it from you to do such a thing—to kill the righteous with the wicked, treating the righteous and the wicked alike. Far be it from you! Will not the Judge of all the earth do right?” (Gen 18:25 NIV).

But I am no longer a Christian and believe that this is only a partial picture. As Eric Cheetham explains, “Sakyamuni saw, without error, the whole of Samsara in all its realms, throughout its entire range in the past, the present, and the future. This immediate and total perception enabled the Buddha to correct the errors of his predecessors and his contemporaries. The true nature of Samsara was revealed to him; the gods did not create it and they did not, control it” (8).

The law of karma, “A man reaps what he sows” (Gal 6:7 NIV), is baked into the nature of conditioned reality. It is a law above the Gods. They became Gods by observing the law. They didn’t create the law and they do not enforce it. They are limited in what they can do.

This means that, “If there is another world, and if there is the fruit and result of good and bad deeds, it is possible that… after death, I will be reborn… in a heavenly world” (AN 3.65 Bodhi). In other words, good people generally go to heaven and bad people go to hell. As the Buddha said, “evil-doers go to hell; the good go to heaven” (Dhp 126 Radhakrishnan). What is interesting is that this is almost universally believed, even by some Christians.

But is “hell” the right word? In Buddhism, all things are impermanent, even hell. Maybe a better word is purgatory. Oxford English Dictionary defines it as “a place or state of suffering inhabited by the souls of sinners who are expiating their sins before going to heaven.” The Catholic Encyclopedia further explains, “Purgatory (Lat., purgare, to make clean, to purify) in accordance with Catholic teaching is a place or condition of temporal punishment for those who, departing this life in God’s grace, are, not entirely free from venial faults, or have not fully paid the satisfaction due to their transgressions” (Hanna).

The Roman Catholic Church makes a distinction between hell and purgatory, but some of the early church fathers did not. They felt that hell was temporary for all. As Wikipedia explains, “Purgatorial Universalism was the belief of some of the early church fathers, especially Greek-speaking ones such as Clement of Alexandria, Origen, and Gregory of Nyssa. It asserts that the unsaved will undergo hell, but that hell is remedial (neither everlasting nor purely retributive) according to key scriptures and that after purification or conversion all will enter Heaven. Judaism teaches something similar – hell is an intense experience of cleansing, more an expression of kindness than a punishment.”

Now in terms of justice, this makes more sense. Heavens and hells are temporary, and once the reward or punishment has been met, one is reborn elsewhere. If you just search your own heart, this seems supremely fair. Do bad things and you get punished, do good things you get rewarded. But neither are everlasting. This is what the Buddha taught.

Level Two: Meditation for Happiness

The Buddha said:

The second assurance he has won is this: ‘If there is no other world, and there is no fruit and result of good and bad deeds, still right here, in this very life, I maintain myself in happiness, without enmity and ill will, free of trouble (AN 3.65 Bodhi).

As we said before, the Buddha clearly believed in an afterlife (MN 60 Bodhi). But heavens and hells are not visible to this realm. You can’t see them, hear them, or touch them. Even in his day, there was a school of philosophy known as the Carvaka and Lokayata. Not only did they reject the Vedas, but, as Pradeep P. Gokhale explains, they disregarded “otherworldly beliefs such as soul, God, rebirth, and other worlds” (17). The Carvakas,” writes Bhupender Heera, “are naturalists (svabhavavadins who reject supernaturalism with all that implies, i.e. God, soul (apart from the body), life beyond the present one (transmigration), existence of hell an heaven (except in this world in the form of natural pleasures and painful existence), karmaphala and adrsta (fate), etc.” (58).

The attitude of the Carvakas is known as materialism, or as it is better known today, naturalism. Webster’s New World College Dictionary (5th ed.) defines naturalism as “the belief that the natural world, as explained by scientific laws, is all that exists and that there is no supernatural or spiritual creation, control, or significance.” “Naturalism,” writes Thomas W. Clark, “holds that there is a single, natural, physical world in which we are completely included. There isn’t a separate supernatural or immaterial realm and there’s nothing supernatural or immaterial about us” (1).

Thomas W. Clark makes a common mistake when he says, “The naturalistic worldview has roots going back to the Buddha” (3). The Buddha actually said, “there actually is another world, one who holds the view ‘there is no other world’ has wrong view” (MN 60 Bodhi). The Buddha said, “Mendicants, there are five destinations. What five? Hell, the animal realm, the ghost realm, humanity, and the gods. These are the five destinations” (AN 9.68 Sujato). How could Thomas W. Clark get this wrong? David L. McMahan explains that “What many Americans and Europeans often understand by the term ‘Buddhism,’ however, is actually a modern hybrid tradition with roots in the European Enlightenment no less than the Buddha’s enlightenment” (5).

But the Buddha did address the question of what use is the Dharma, “If there is no other world.” His answer? The benefits of practicing the Noble Eightfold Path can be seen in “this very life.” How? “I maintain myself in happiness, without enmity and ill will, free of trouble” (AN 3.65 Bodhi). This shows, notes Soma Thera, “that the reason for a virtuous life does not necessarily depend on belief in rebirth or retribution, but on mental well-being acquired through the overcoming of greed, hate, and delusion.”

Since I wrote the first book with the title “Secular Buddhism,” let me defend it here. “Secular Buddhists don’t believe in a literal rebirth after death, or the supernatural for that matter” (Forrest 17). I think Secular Buddhism is a legitimate form of Buddhism for the scientific West. By “legitimate” I don’t mean it is Buddhism as the Buddha taught it. It is not. But legitimate in the sense of being “genuinely good” (Merriam-Webster.com).

Secular Buddhism operates on the 2nd level of Buddhism, the level where meditation brings happiness in this life. In this sense, it shares common ground with modern psychology. As Miriam Akhtar notes, “Meditation began as a spiritual ritual in the East and has now been adopted as a health practice in the West” (93). As Time magazine reported, “we’re in the midst of a popular obsession with mindfulness as the secret to health and happiness – and a growing body of evidence suggests it has clear benefits” (Pickert).

The simple fact is that not everybody is going to buy into the whole karma, rebirth, heavens, hells, Gods, demons, angels, and nirvana stuff. I didn’t for years. So I understand where these people are coming from. Science doesn’t provide us with enough evidence that such things exist. But the Buddha said that even then, with the wrong view, one can and should still practice as much of the Dharma as possible. Happiness in this life is a goal we can all strive for.

Level Three: Wisdom for Nirvana

The Buddha said:

Some enter the womb; evil-doers go to hell; the good go to heaven; those free from worldly desires attain nirvana (Dhp 126 Radhakrishnan).

So we have talked about people interested in heaven, and we have talked about people interested in happiness, but what about those of us who want to get off the Merry-go-round of birth, sickness, old age, death, and rebirth? This desire was not unique to Buddhism. It was a common theme in India. But the Buddha actually attained liberation and was able to discern the unconditioned.

The Buddha said:

“There is, monks, an unborn, unbecome, unmade, unconditioned. If, monks there were not that unborn, unbecome, unmade, unconditioned, you could not know an escape here from the born, become, made, and conditioned. But because there is an unborn, unbecome, unmade, unconditioned, therefore you do know an escape from the born, become, made, and conditioned” (Ud 8.3 Anandajoti).

There are two realities, a conditioned reality and an unconditioned reality. The “five destinations” of “Hell, the animal realm, the ghost realm, humanity, and the gods” are part of the conditioned reality (AN 9.68 Sujato). Only nirvana touches the unconditioned reality.

As the Buddha said, “Greediness is the worst disease; propensities are the greatest of sorrows. To him who has known this truly, nirvana is the highest bliss” (Dhp 203 Radhakrishnan). The key is that one has to have “known this truly” before they realize that “nirvana is the highest bliss.” You don’t know what you don’t know. But if you make steps on the journey of awakening, reality will slowly unveil itself in its true colors. Until then, attachment and ignorance bind us.

Works Cited

References for Translations can be found on the Translations Used page.

- Akhtar, Miriam Positive Psychology: Self-Help Strategies for Happiness, Inner Strength and Well-being. Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky, 2012. Print.

- Cheetham, Eric. Fundamentals of Mainstream Buddhism.Boston: Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1994. Print.

- Clark, Thomas W. Encountering Naturalism: A Worldview and Its Uses. Center for Naturalism, 2007. Print.

- Forrest, Jay N. Secular Buddhism: An Introduction. Albuquerque, NM: J.F. Books, 2016. Print.

- Gokhale, Pradeep P. Lokayata/Carvaka: A Philosophical Inquiry. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2015. Print.

- Gombrich, Richard F. How Buddhism Began: The Conditioned Genesis of the Early Teachings. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvd Ltd., 2010. Print.

- Hanna, Edward. “Purgatory.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 17 Sept. 2020. Web.

- Heera, Bhupender. Uniqueness of Carvaka Philosophy in Traditional Indian Thought. New Delhi: Decent Books, 2011. Print.

- McMahan, David L. The Making of Buddhist Modernism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. Print.

- Pickert, Kate. “The Art of Being Mindful.” Time. 3 Feb 2014, pp. 40-46. Print.

- Soma, Thera. “Kalama Sutta: The Buddha’s Charter of Free Inquiry.” Access to Insight (BCBS Edition), 30 November 2013. Web.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Christian universalism.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 7 Sep. 2020. Web. 17 Sep. 2020. Web.

Copyright © 2020 Jay N. Forrest. All Rights Reversed.

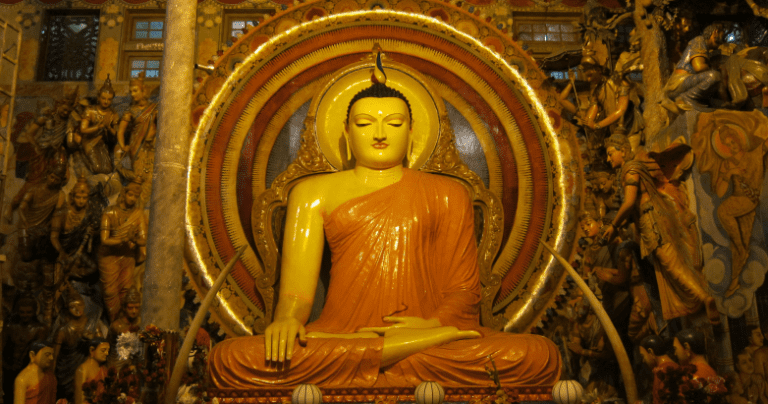

Image by Indi Samarajiva via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)