The Buddha said:

The bhikkhu who experiences great joy, and has faith in the religion of the Buddha, will attain the place of peace, the satisfaction of stilling the functions of the mind. When a bhikkhu applies himself when still young to the religion of the Buddha, he illuminates the world, like the moon breaking away from a cloud (Richards Dhp 381-382).

Here John Richards translates both instances of Buddha-sasana as “the religion of the Buddha.” I think this is an excellent dynamic equivalent translation, but blogger Alan Gregory Wonderwheel disagreed with translating sasana as “religion.” Here is my answer.

The Translation Styles

Here a much older translation by Albert Joseph Edmunds, “The monk yet young, who unto Buddha’s religion devoteth himself, brighteneth this world, as the moon from cloud set free” (Edmunds Dhp 382). Why did he translate Buddha-sasana as “Buddha’s religion”?

I learned to translate the Greek New Testament in Bible College. The more I learned, the harder it was to translate a passage. For example, my completely literal translation of John 1:1 is, “In [the] beginning the Logos was, and the Logos was facing the God, and the Logos was God” (Forrest, 126). The common reader will not understand this.

On the other end of the spectrum is the paraphrase, where you put the passages in your own words. For example, my paraphrase of John 1:1 is, “Before the beginning [of creation] the Revealer [of God’s thoughts and character] existed, and the Revealer was beside God [the Father in intimate fellowship], for the Revealer was God” (Forrest, 757). This brings in a lot of interpretation. The interpretation may be right or wrong.

Between these two is the dynamic equivalent (or functional equivalent). Using John 1:1 again, the New Living Translation renders it: “In the beginning the Word already existed. The Word was with God, and the Word was God.” This brings in just enough interpretation to make it understandable.

So here we have the three basic translation styles, the formal equivalent, the dynamic equivalent, and the paraphrase. Each has its strengths and weaknesses. Legal documents usually follow a formal equivalent method of translating. Most modern Bibles follow the dynamic equivalent method of translating. Paraphrase is used more for commentary work.

Dynamic Equivalence

I believe the best method of translation for the Buddhist scriptures is the dynamic equivalent method of translating. For that reason, I want to explain what it is to those who may not know.

Eugene A. Nida was a linguist who developed the dynamic equivalence theory of translation, primarily for Bible translation, but used widely. Here is his definition of dynamic equivalence, which he later renamed functional equivalence:

Dynamic Equivalence is to be defined in terms of the degree to which the receptors of the message in the receptor language respond to it in substantially the same manner as the receptors in the source language (Nida, Theory and Practice 24).

From Nida’s point of view, translation means translating meanings. This is important. Many literal translations are worried about the letter and miss the spirit of the message. Only those who are unaware of the struggles of translating understand that there are few direct and complete equivalence of words between two languages. There is almost always a loss of meaning from the original and a gaining of unintended connotations from the new language.

Concerning a dynamic equivalence translation, Eugene A. Nida writes, “in such a translation one is not so concerned with matching the receptor language message with the source language message, but with the dynamic relationship, that the relationship between receptor and language should be substantially the same as that which existed between the original receptors and the message” (Nida, Toward a Science 159). This means that the “dynamic equivalence is therefore to be defined in terms of the degree to which the receptors of the message in the receptor language respond to it insubstantially the same manner as the receptors in the source language” (Nida, Theory and Practice 24).

Eugene A. Nida is primarily concerned with the message being received. According to him, “intelligibility is not to be measured merely in terms of whether the words are understandable and the sentences grammatically constructed, but in terms of the total impact the message has on the one who receives it” (Nida, Theory and Practice 22). According to Nida, “translation consists in reproducing in the receptor language the closest natural equivalent of the source language message, first in terms of meaning, and secondly in terms of style”(Nida, Theory and Practice 12).

This process is not necessarily easy. “We must analyze the transmission of a message in terms of a dynamic dimension. This analysis is especially important for translating, since the production of equivalent messages is a process, not merely of matching the parts of the utterances, but also of reproducing the total dynamic characters of communication.” (Nida, Toward a Science 120). Nida places special emphasis on the expressive function, “one of the most essential, and yet often neglected, elements is the expressive factor, for people must also feel as well as understand what is said” (Nida, Theory and Practice 25).

Buddhist scriptures have several problems to overcome. The first is the tedious repetition. This may be great for remembrance but it makes reading tiresome. There is a reason that only the Dhammapada has been widely disseminated. It is the most unlike the other sutta collections. This is also why the Mahayana sutras are more popular, though much later than the Buddha.

The second obstacle is the cultural linguistic gap between ancient India and the modern West. Only the dynamic equivalent method of translating can bridge this gap without slipping into paraphrase. And even here, paraphrase might be the best option in some cases.

Meaning and Phrasing

The Buddha once said:

The venerables agree on the meaning but disagree on the phrasing. But the venerables should know that this is how such agreement on the meaning and disagreement on the phrasing comes to be. But the phrasing is a minor matter. Please don’t get into a fight about something so minor (MN 103).

The point in teaching the Dharma is that it be understood correctly, not which words are used. For example, some prefer to use the Pali word dhamma, while others, like myself, prefer the better known Sanskrit Dharma. The reason is very simple. Dharma is in most English Dictionaries, such as the Oxford English Dictionary, and dhamma is not. But the Buddhist meaning of both is the same. Both Buddha Dharma and Buddha dhamma refer to the “teaching of the Buddha.” I think “the phrasing is a minor matter.”

Buddha-Sasana as “the Teaching of the Buddha”

The Concise Pali-Enlight Dictionary defines sasana as “teaching; order; message; doctrine; a letter” (Buddhadatta). Clearly, a literal translation of sasana is “teaching.” Here are two translations of Buddha-sasana using “teaching” and not “religion.”

A young monk who strives in the Awakened One’s teaching, brightens the world like the moon set free from a cloud. (Dhp 382 Thanissaro)

That monk who while young devotes himself to the Teaching of the Buddha illumines this world like the moon freed from clouds (Dhp 382 Buddharakkhita).

But doesn’t Dharma mean “teaching”? Translating sasana as teaching seems redundant. In Pali, they have very different connotations and connections.

Dynamic Equivalence of Buddha-Sasana

Bhikkhu Nyanatiloka explains that the literal translation of sasana is “message.” He then defines it as “the Dispensation of the Buddha, the Buddhist religion; teaching, doctrine.” In his Glossary, Bhikkhu Bodhi defines sasana as “Dispensation (of Buddha)” (Nanamoli 1383). In his Index of Subjects he lists a number of passages where sasana (MN 56.18; 65.4, 14ff.; 70.27; 73.13f.; 74.15; 89.12, 18; 91.36; 122.25f.; 137.22ff). I doubt most people will know what a Dispensation is. Webster’s New World College Dictionary (5th ed.) defines it as “Any religious system.” It seems “religion” would have been a better dynamic equivalent.

The best dynamic equivalent for the Pali words Buddha-sasana is the “Buddha’s religion.” Bhikkhu Sucitto defines Buddha-sasana as “the Buddhist religion” (Sucitto 52). The Encyclopedia of World Religions says this about Budda Sasana: “Term equivalent of the Buddhist religious tradition involving the community, rituals, ethics, social involvement and spirituality originating from the Buddha.”

Let me offer further evidence. A Dictionary of Buddhism by Damien Keown says that sasana is “a term used by Buddhists to refer to their religion” and Buddha-sasana is used “especially in the context of their historical continuity as a religious tradition.”

The Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Religion says that sasana is “a Buddhist term for what is usually translated as religion in the West.” The Concise Dictionary of Religion under the entry of Buddhism says: “the Western name for the religion of the Buddha, known in Asia as the Buddha-Sasana, or path of discipleship.”

Wilhelm Geiger chose to translate sasana as religion in Buddhist Legends. And Walpole Rahula wrote this in his History of Buddhism in Ceylon: “the purification (sodhana) of the Sasana (religion)” (Carter).

Some Examples

The Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics says that “sasana can rightly be translated ‘the faith,’ ‘religion,’ ‘the church.’” Now clearly the best of these three choices is the word “religion.” Let’s see how this works in a number of passages:

For a faithful disciple who is practicing to fathom the Teacher’s religion, the Teacher’s religion is nourishing and nutritious (MN 56).

He went beyond doubt, got rid of indecision, and became self-assured and independent of others regarding the Teacher’s religion (MN 74).

Clearly these venerables have realized a higher distinction in the Buddha’s religion than they had before (MN 89).

He went beyond doubt, got rid of indecision, and became self-assured and independent of others regarding the Teacher’s religion (MN 91).

But their disciples don’t want to listen. They don’t pay attention or apply their minds to understand. They proceed having turned away from the Teacher’s religion (MN 122).

Ruth Streicher and Adrian Hermann report that “the standard translation of ‘religion’” into Siamese is “the traditional Buddhist term sasana” (1). Now it is interesting that the equivalency of “religion and “sasana” is understood by Thai scholars, but is not as clear to some in the West.

The Religion of the Buddha

I understand why some want to avoid the word religion. For many it means the belief in and worship of God. Buddhism is not that type of religion. But it is still a religion and is in every major book on world religions.

A religion is a worldview and way of life that is related to the Divine or sacred. There are at least three elements in a religion. They have a worldview, a way of life, and something Divine or sacred. A worldview is the belief system or conceptual framework we use to see and interpret the world. A way of life deals with the personal, ethical, and social ways that we act in the world. In Buddhism, the sacred is the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. Buddhism is Humanistic rather than Theistic. It is centered around ultimate liberation for humans.

So Buddhism is a religion. “Religion” is the best dynamic equivalent for the Pali word sasana. It might literally mean message, but its connotation includes the idea of an order, a dispensation, a religion.

“When a bhikkhu applies himself when still young to the religion of the Buddha, he illuminates the world, like the moon breaking away from a cloud” (Richards Dhp 382).

Works Cited

References for Translations can be found on the Translations Used page.

- Buddhadatta, A.P. Mahathera. “Sasana.” Concise Pali-English Dictionary. Delhi: Motilal Barnarsidass Publishers Private Limited, 2014. Print.

- Carter, John Ross. “A History of Early Buddhism.” Religious Studies, vol. 13, no. 3, 1977. Web.

- Concise Dictionary of Religion, The. “Buddhism.” Irving Hexham. Canada: Regent college Publishing, 1993. Web.

- Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Religion (vol. 3). “Sasana.” Ramesh Chopra, ed. Delhi: Gyan Publishing House, 2005. Web.

- Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics (Vol 11). “Sasana.” James Hastings, ed. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. 1921.

- Encyclopedia of World Religions. “Buddha Sasana.” Bruno Becchio and Johannes P. Schade, eds. Netherlands, Concord Publishing, 2006. Web.

- Forrest, Jay N. Christian Theology: Biblical, Devotional, Spiritual, Innovative. Albuquerque, NM: Christoas Theologia, 2015. Print.

- Keown, Damien. “Sasana.” A Dictionary of Buddhism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Nanamoli, Bhikkhu and Bhikkhu Bodhi, trans. The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Majjhima Nikaya. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2009. Print.

- Nida, Eugene A. and Charles R. Taber. The Theory and Practice of Translation. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1969. PDF file.

- Nida, Eugene A. Toward a Science of Translating. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1964. PDF file.

- Nyanatiloka, Bhikkhu. Buddhist Dictionary: Manual of Buddhist Terms and Doctrines. Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society, 1997. Print.

- Streicher, Ruth and Adrian Hermann. “‘Religion’ in Thailand in the 19th Century.” In Companion to the Study of Secularity. Edited by HCAS “Multiple Secularities – Beyond the West,

- Beyond Modernities.” Leipzig University, 2019. Web.

- Sucitto, Bhikkhu. Sangha Words: a Manual for Forest Sangha Publications. Revised Edition Version 1.2. Hemel Hempstead, England: Amaravati Publications, 2016. PDF file.

Copyright © 2020 Jay N. Forrest. All Rights Reversed.

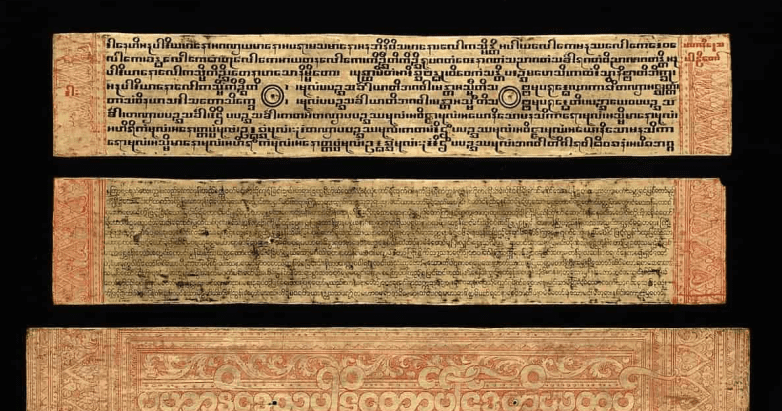

Image by Wellcome Library, London via Store norske leksikon (CC BY 4.0)