The way things are going, we may be in for another Bush v. Gore-esque 38-day slog. Election day is almost a week old, but the election season is young yet.

In any case, the temptation to think little of our governmental institutions and constitutional order will be strong. Many are actively debasing it (and have been for some time). Let the notes from a 1744 election sermon below act as a shield against this tendency.

***

James Allen (or sometimes “Allin”) was born in Roxbury, Massachusetts in 1692 (d. 1747). Roxbury, of course, was the home of John Eliot (1604-1690)–who drafted the controversial, Christian Commonwealth (1659), espousing his vision of government–and also the birthplace of John Wise (1652-1725). (There is much similarity between Wise’s description of government at one point in the Vindication of the Government of New England Churches (1715/1717) and Allen’s sermon below; the point of convergence will be noted below for the sake of those few interested, but mainly to serve as a future note to myself.)

Allen graduated from Harvard in 1710, and ministered until the end of his life at the first congregational church of Brookline, Massachusetts, then a newly incorporated town (1705). For nearly over decade the town, being relatively poor, was unable to gather the funds to build a church and hire a minister. In 1718, Allen became their first, aged 26. Other than his delivery of the 1744 election sermon (which, at 54 pages, is comparatively long to others reviewed here), little else is known about him.

According to a brief biography (not 20 pages long) published by the Brookline parish in 1900, Allen died three years after preaching on election day and his wife followed six months later; his son, the year after, and his daughter and her fiancé also within two years of Allen’s son. And so, tragically, in the span of a little more than three years, the entire Allen family was wiped out. The notes below refer to one of the few known published works by Allen, his 1744 election sermon entitled, “Magistracy an Institution of Christ Upon the Throne.”

***

Isaiah 6:1: In the year that King Uzziah died, I saw the Lord sitting upon a Throne, high and lifted up.

Allen launches his sermon by invoking the familiar Psalm 19:1.

“Now if God had wisdom to contrive, and power to effect these beautiful globes, he has an indisputable right to the government of them, and is certainly qualified for it.”

This is not only a nod to the revelation of God imprinted upon the book of creation, but also to his immanence and providence. Allen decidedly rejects the clock winder God of the atomists of his day:

“to suppose, that, when he had made the world, he took no further thought or care, but left it to shift for itself, implies one or other of these absurdities, that he either made it for no wise design, or through some mistake in its formation it did not answer his original purpose.”

God is no “unskilful artificer, not having framed his work according to the model of it in his own mind.” He is a purposeful, careful creator who would not leave his own glory and self-representation to chance. On the contrary, the world and everything in it “is a most wise production, that has no blotches or blunders in it, but in all its parts exquisitely done, and every way correspondent to the design in the eternal mind.” Accordingly, “there can be no reason upon this account why he should not govern it.”

Indeed, God is actus purus; absolute actuality and absolute perfection. That he is metaphysically and morally immutable and essentially simple does not negate his pure actuality and constant activity–deriving nothing from outside himself (no shadow of change) and neither effected thereby. His care for creation and dictation of providence is intricate and constant, and always everywhere conducted in accordance with the eternal counsel of his own will.

As Aquinas well noted, the good of things–and all things created by God must be good else we must predicate some evil of God–is not only found in their substance “but also as regards their order towards an end and especially their last end.” And since the end to which a thing is ordered must dictate its essence and existence, the end of a created thing must pre-exist in the divine mind. That is, the end was determined, in a sense, before the things itself.

Now, not only does God perfectly know and perfectly determine–for he cannot know what he does not will and vice a versa–the end of the thing in view, but he also ensures its actualization, that is, the meeting of the thing with its end, and especially its final end, but not less its immediate end(s). (Romans 8:28 is not irrelevant here.) This, says Aquinas, is “properly speaking, providence.” And the ordering of things to their proper end is prudence. Therefore, providence is the “chief part of prudence”; all human prudence is derivative thereof. (Hence, why Puritans often spoke of being in step with providence– the well ordering of things according to their proper end(s) evident from nature, reason, and Scripture.) This is also why prudence is the first of the classical virtues (and why Cicero designated memory, understanding, and foresights the three parts of prudence, on this see Aquinas, Summa, II-II, Q.48, A.1).

Allen is right, therefore, to root his discussion in the doctrine of God and his providence, thereby attributing to God the governance of all of creation, including the institutions of man. If God has an end in view of his creation then it is absolutely necessary for him to govern creation unto that end–both implicitly and explicitly. It is a demonstration of “the glory of his perfections” to preserve “several ranks of beings, in that harmonious and admirable order they were placed in at first.”

This recalls also John Arrowsmith’s comments on Genesis 1:

“Briefly, God made Something of Nothing, and then out of that Something, made All things, as one well expresseth it. That which (Gen. I.) is called the earth, and the water, and the deep, that first matter, it was made out of meer [sic] nothing. There is something out of nothing, and then out of that first Matter were all things framed. There is all things out of something; so as, mediately or immediately, all the Creatures come out of Nothing. There is Non-ens negativum; And so the first matter, commeth out of nothing. There is, Non-ens privativum; And so the other things, they came out of that which is, Non-ens tale, a thing that had no naturall dispostion to receive such a form. And here is the omnipotency of God seen in both. For it requires as much power to produce such and such formes [sic], as to produce that first matter out of Nothing; and yet, This, God hath done.”

***

God not only created something out of nothing but then more somethings out of the first somethings. Put another way, God works both directly and indirectly according to his divine will and providence, and both are equally impressive. That God works through means–the means he created for himself–makes his omnipotence also immanent, and his providence both more intricate and more attentive. To say otherwise is to “limit the most high, debase his excellencies, and bring him down upon a level with his creatures.” Our creatureliness prevents us from fully comprehending (or even imagining) this truth, and so, “It becomes us better,” says Allen, “to confess and adore with the psalmist, than to object against providence, The Lord reigneth, he is clothed with magesty.” Because of the mystery surrounding, but fundamental goodness of, God’s providence, we may rejoice in tribulation and even when “surrounded with greatest dangers” and when “thick and black cloud have impended over the church or state, and threatned [sic] its subversion.”

It also presents the duty for Christians to “acknowledge God in all our ways, and implore his direction in an affair of the highest importance, and wherein the interest of the province, both civil and religious, is so nearly concerned.” (n.b. notice, again, the nod toward a more integralist vision of society, or what has aptly been dubbed “political Augustinianism;” the church and state are part of the same province and both, as coordinate powers, concerned in the election of Allen’s day.)

Allen goes on to remind his audience that even the wisest and best rulers, like every other mortal, die. The long and prosperous reign of Uzziah still came to an end. “Whatever distinction God, in his providence, has made betwixt one man and another, in civil respects, they are all in death’s account equal.” “It is the prerogative of him [only], whom the prophet saw upon the throne, to be the King Eternal.” Hence, all rulers are under Christ’s feet; their derivative power is established and granted by Christ alone who possess the authority to distribute it. It is this king that the prophet saw seated upon the throne in his vision (see also Rev. 5:1). It is this king that is God and is with God, even from the foundations of the earth. He is, therefore, qualified for its administration, the earth he created in the unified, triune act (though, to be clear, it was specifically the second person of the trinity that the prophet caught a glimpse of).

Allen:

“He sets upon a throne of government, giving out his laws, and demanding our obedience, and observing what regards we pay to them, that he may reward or punish us accordingly: For th throne of judgment is also his; and at his word we either stand or fall.”

Isaiah: Then I said, wo is me, I am undone.

***

Allen reflects that this “subject is truly sublime,” and “full of mystery,” and, therefore, “we may never expect to comprehend it while in our present state of imperfection.” Nevertheless, advantages abound to those who would ponder its truth and moral weight, if imperfectly.

First, Christ exaltation to the throne provides Christians with assurance that he has the power, purpose, and will to care for his creatures. He is an efficient and sufficient ruler over all creation. None share in his dignities. He is the “eternal head of government” of all things. All else below him is folly. The grandeur of his throne, his rule, is unsurpassed. All lower governments are under his feat and, therefore, as already stated, are derivative of his insofar as they have authority and power at all. That is, none rule lest Christ bid them to. In the same way, Christ’s enthronement assures us of salvation, that redemption has been accomplished and applied (and preserved)–for his present rule is predicated on said accomplishment; Christ’s glory is attached thereto; neither he nor the father will let it falter. Of course, Christ’s priestly intercession for us is also guaranteed thereby.

Secondly, as already alluded to, Christ upon his thrown (as Isaiah caught a glimpse of) “denotes his actual government over all things… The Government of the world is upon his should…” There is no other ultimate source of the governing of creation and the affairs of men than Christ. All other explanation exist only in the “absurd imaginations of men.” And “there is no imprudence or injustice in Christ, in his whole management.” Some epochs of history, or even discrete moments, may seem disorderly or confused, but this is only the case “because our faculties are not strong enough to see into the amazing depths of wisdom contained in them.”

Hence,

“The great and sudden changes in publick [sic] affairs; the revolutions of states and kingdoms, which surprize [sic] and astonish us, are the effects of a designing mind, of an alwise [sic] cause. The various conditions and circumstances of men, that some are prosperous, others adverse; some rich, and others poor; some in dignity, while others are low and level with the earth; is not the result of meer [sic] chance, but design of Christ, and for wise ends. The beauty and glory of the whole consists very much in the variety of its parts: And the qualifications of men, for the different stations and parts they are to act, in the rank of rational beings, from Christ the fountain of wisdom.”

Again, in providence, Christ accomplishes this by means.

“Thus Christ upon the throne is the Lord of all, and has authority and power sufficient to govern all by himself, and without the instrumentality of men or angels; but he is pleased to make use of them in the conduct of his affairs both civil and ecclesiastical.”

(n.b. again, we should notice to whom Allen attributes authority over both civil and ecclesiastical power.)

To reiterate and bring Allen’s message home:

“The distinction of king and subject, rulers and ruled, is not the contrivance of designing men, but of divine ordination: ‘Tis Christ upon the throne that has appointed magistracy, that advances men to superiour [sic]or subordinate offices, and accomplishes them for government; and has declared to us for what end he doth it, and accordingly what the people over whom they preside may expect from them, and they from him as they behave and manage in their respective spheres; and also what regard he will have us pay them.”

In particular, then, “magistracy [i.e. magistrates collectively or, in general, governmental power] is an institution of Christ upon the throne.” This institution was imposed upon man “not as a burden, but as a blessing.” Without it, chaos would rule.

“An ungovern’d society of men would be no better than a herd of savage beasts… It was an unhappy juncture when there was no king in Israel to restrain the boisterous lusts and headstrong passions of the people… Where all authoritative & coercive power is taken off, men will soon think that where there is no law, there is no transgression, and make it evident that it was not so much the dread of hell, as of a halter, that restrained them from the greatest villanies.”

Here, Allen employs an analogy between government and human bodies, as so many of his contemporaries and predecessors had. (see John Cotton’s Discourse on Civil Government.)

“A common-wealth without government is like a body without eyes, which stands exposed to a thousand mischiefs, but can defend itself from none of them: To take away government, would be to deprive mankind of all that is civil and sacred, and to reduce a beautiful world to a meer [sic] chaotical state of darkness and confusion; but well-ordered common-wealth how beautiful and glorious to behold.”

(“And how happy the British constitution!” Allen adds.) Allen posits that even if government were not a direct institution of Christ, it appears so reasonable that men, eventually, would have

“been so fully convinced of the absolute necessity of it, that they would not have continued long without it. Anarchy is such a state as no reasonable man would choose, there being no manner of safety in it, either of life or property… Nothin is so adapted to the state and priviledge [sic] of humane nature as government, without which it is impossible that families, cities or nations should subsist.”

Allen then waxes eloquent about the myriad instances of hierarchical order in nature, but then asserts that though government is an institution of Christ, no particular form is mandated (“the apostle expressly says [it] is an human ordinance”). It the case were otherwise, “he would undoubtedly have expressly revealed it.” Even Israel, “his favourite [sic] people,” changed their government no less than five times. Prudence, not explicit divine writ, according to the tempers of the people and the circumstances, must dictate (within reason) the form of government.

As the Westminster Confession of Faith *1646) reads (1.6),

“there are some circumstances concerning the worship of God, and government of the Church, common to human actions and societies, which are to be ordered by the light of nature and Christian prudence, according to the general rules of the Word, which are always to be observed.”

What is important is that the selected form of polity (in church or state) enable the body to perform the prescribed duties of the respective body according to scripture. This is what it means for something to be either agreeable with, or not contrary to, Scripture, but according to the light of nature and Christian prudence. (I do wish a good bit more of this understanding of governance generally would be injected into intramural church polity debates.) (See also John Wise, Vindication, II.I.)

***

The above being the case, certain unique implications arise. If the mediate origin of government, according to its form, is in the prudence of the people, then so too does its failure to govern well fall upon the same people. Resisting reformation when needed–or setting up a faulty polity–is the fault of the people. Now, Allen, having established magistracy by Christ’s power alone, does not mean to say that governmental authority proceeds from the people, rather that a particular society is the mediate cause, or the means through which authority is distributed to those ordained by God. The ruler may be limited by the constitution he rules under, but if the constitution restrain him from fulfilling the fullness of his magistral duties, then those who originally formed the constitution are to blame. Further, once office is conferred upon a man, it cannot be easily or wantonly revoked– because the people, themselves, are not the owners of magistral power but simply a momentary conduit for it.

Make no mistake, “The powers that be, are ordained of God, and no man taketh this honour to himself.” Allen had already established earlier that Christ, in orchestrating providence, employs earthly means to accomplish his ends. The role of the people in either electing rulers or setting up constitutional regimes is just that, a means to Christ’s end, one way or another. What is clear is that magistracy does not originate in the populace (and the populace is not an ordained office). “It is by the mediation of men, that rulers are constituted, from the king upon the throne, to the lowest officer under him.”

Allen makes all of this clear by rebuking those “fanaticks [or “enthusiastick sectaries”], that, in the strongest terms, have denied the divine right of civil rulers; and asserted that no man’s conscience was bound to a submission to them, and to oppose their authority.” Allen astutely notes the distinct millenarianism of radical sects. It is always the cause of establishing Christ’s throne on earth–as if he had need of their assistance–that has led men of such persuasion to defy earthly authority, the pretense that justifies subverting the very thrones that Christ has ordained for his own glory and use. Government is an ordinance of man not because it is subject to man’s whim, but because it is a blessing for him. “The civil ruler is expressly called God’s minister.” To unjustly resist this authority, then, is not only to defy Christ’s authority but to spit upon his blessing.

***

If rulers are called “gods” then the heavenly God, his justice and wisdom, must be a pattern for them, the former being derivations of the latter (“it is their duty and glory to imitate him herein”). And this begins in their paternal service )”They are stile nursing fathers… they are to watch night and day, and always contriving and active for the prosperity and welfare of their people”). We’ve seen this invocation of Isaiah 49:23 before from other election day preachers, so I will not dwell on it. But note well that Allen emphasizes the public religious duties of magistrates:

“[T]hey should be especially concerned to promote the honour and interest of religion among the people, by good laws, and their good example: it is the main qualification of a governour, that he endeavors to make his subjects good men and good Christians, obsequious to the laws of God, and loyal to the crown of heaven.”

A good ruler are to be “a guardian to his churches, a patron of virtue, a promoter of learning, and to shine in all the graces that adorn the Christian.” He is to “advance religion of God our Saviour,” that is, Christianity. Christ is “greatly exalted, when princes and governours and inferiour officers exert their power to promote the kingdom and interest of Christ, and to defend their people from insult and oppression.” Hence, “it was given in charge by the God of Isreal, to the electors of the empire to chuse [sic] the person that he should nominate to be their king; and to the king so eelected, toa ct under the influence of religious laws in his administration, Deut. 17.18.” This kind of fealty to true religion was promised to prolong the government of a ruler and bless his posterity.

To these qualities, Allen adds that rulers must be wise, experienced, just, and exhibit a “publick spirit; seeking the good of all their people.” But just as the basis and authority of magistracy itself comes only from Christ upon the throne, so too do these characteristics of a good ruler. Top to bottom, the Christian must trust in providence for a good government, competent and righteous ruler, and national prosperity and tranquility. But even when these things are withheld from a people for a time, Christ remains upon his throne and works all things unto his glory and for the ultimate good of those who are in him.

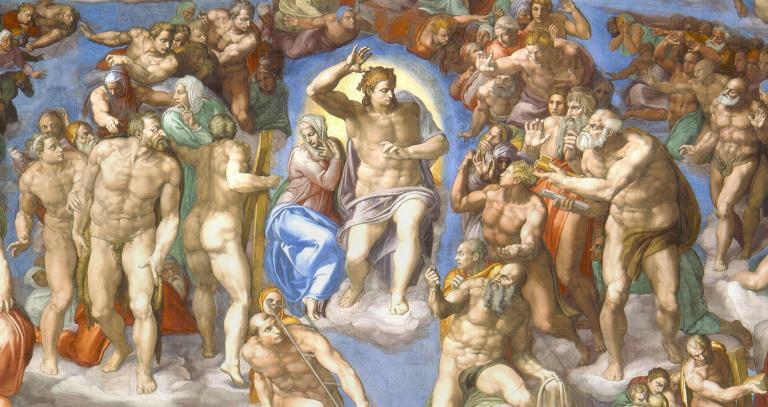

Image: The Last Judgment, Michelangelo (1536-1541), Sistine Chapel, Vatican City (Wikimedia Commons)