Universities are complex places that influence young minds. Sometimes that influence is scattershot: a little history here, a little biology there. Other times, though, there is an integrating principle that holds together the otherwise disparate influences of professors and subject matter. Historically speaking, only the latter constitutes a true university, at least in its etymological sense of the various disciplines “turning as one.” The former model, while now the one that prevails at some universities, is more properly described as a “multiversity” or “pluriversity.”

I have argued elsewhere that the first model–more a shopping mall than an education– reflects a consumer imagination about the world (see this also). The second model is exponentially more difficult to pull off, because it requires that faculty of different disciplines talk to each other about not only their area of expertise, but about broader questions like human flourishing, sin and grace, science and the person, and so on. More fundamentally, it requires what Charles Taylor calls a social imaginary, a way of imagining the world and our place in it.

Consider some basic questions: what has shaped the way you imagine the world? What do you do when you have free time? What do you find entertaining? What do you watch on TV or at the cinema? What kind of music do you like? What do you find funny? What kind of banter do you engage in when you let your hair down with friends? Who is the coolest person you can think of? What constitutes success? What would you die for?

These are clues to your perception of the social imaginary. Taylor unpacks a modern social imaginary, focusing on the significant changes wrought by the emerging economic order of the eighteenth through twentieth centuries. (See his books Modern Social Imaginaries and A Secular Age.)

My hypothesis is that central to Western modernity is a new conception of the moral order of society. At first this moral order was just an idea in the minds of some influential thinkers, but later it came to shape the social imaginary of large strata, and then eventually whole societies. It has now become so self-evident to us, we have trouble seeing it as one possible conception among others. The mutation of this view of moral order into our social imaginary is the development of certain social forms that characterize Western modernity: the market economy, the public sphere, the self-governing people, among others. (citation)

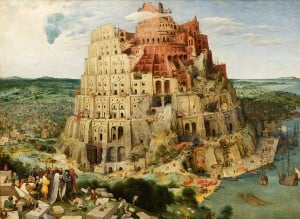

The bottom line: commerce changes everything. We imagine a cosmopolis in which the economy serves all human goods; technology cures all human ills; sexual commerce permeates all relationships; entering and exiting human life is tightly controlled. The goal of the university becomes the formation of the smart consumer.

Catholicism has always been about imagining a new world. From Jesus’ colorful parables to the monastic retreat into the desert; from the catacombs to the basilicas representing artistically a new heaven and a new earth; from the rise of Christendom (even in its debased, military form) to the foundation of religious orders bound by vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience; from the founding of pawn shops to help the poor, hospitals to help the sick, schools to help the ignorant, and so on.

The culmination of this theological imaginary (my term) is the new Jerusalem described by the prophets and in the book of Revelation: the city where justice prevails–that is, right relationship among people, and between people and God. “The kingdom of heaven is at hand,” Jesus preached: not in a far-off future, but right now. The university rooted in a Catholic theological imaginary is fundamentally about shaping this new way of imagining the world.

Photo credit: Romary (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC BY-SA 2.0 fr (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/fr/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons.