Scot McKnight is one of my favorite New Testament scholars and theologians. He is coming to Asbury Seminary later this semester to speak and I cannot wait! McKnight’s work over the years has been a major influence in my own faith and scholarly development. His short, yet very powerful essay, Junia is Not Alone (Patheos Press, 2011), basically opened the door for me to become an egalitarian evangelical. He and others like Ben Witherington, Craig Keener, and N. T. Wright have provided me with the language and paradigm to root my stances deeply in exegetical and theological argumentation. Reading that little essay of McKnight’s even inspired my senior thesis research in my undergraduate work. Many of his other books, such as The King Jesus Gospel (Zondervan, 2011) and A Long Faithfulness (Patheos Press, 2013), have proven to be equally influential on me. McKnight is one of those key thinkers who continually helps me to be a Scripturally and theologically rooted, orthodox, egalitarian, Wesleyan-Arminian in an evangelical world that sometimes feels full of complementarian, John Piper-style Calvinists (as opposed to European and Barthian-style Reformed thinkers, whom I deeply love to read and agree on much with).

McKnight also hosts an excellent podcast called “Kingdom Roots” where he talks about various topics related to biblical studies, theology, and the Christian life. In one of the recent episodes (“The Hum of Angels” KR-36 on the iTunes link), Scot takes up the topic of angels. In conjunction with his forthcoming book, The Hum of Angels: Listening for the Messengers of God Around Us (Waterbrook, 2017), the episode provides a fascinating discussion of angels in both a biblical and historical context. The whole episode is excellent and I’d highly recommend listening to it. The discussion reminded me of my own interest in the realm of those non-human/non-animal personal beings Stanley Grenz calls “our spiritual co-creatures.” As Grenz notes in his Theology for the Community of God (Eerdmans, 2000):

Biblical faith asserts that we are not alone in the universe. Our world is populated by other life forms, of course. In addition to the physical creatures, the biblical authors indicate that spiritual realities also participate in God’s created realm. Like humans, these realities are moral agents, responsible to God to fulfill a divinely given mandate (p. 213).

McKnight’s discussion of angels reminded me of how much our modern consciousness has almost entirely dismissed the biblical conception of angelic beings, while at the same time the a significant portion of people in the U.S. continue to believe in them (Scot notes figures from the Baylor Religion Survey stating that 88% of women and 74% of men believe in angels). While this is understandable in a secular context, what is somewhat disturbing is how many Christians seem to dismiss the angelic realm.

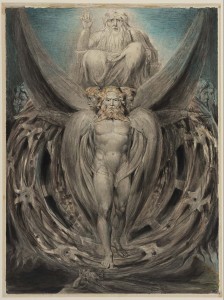

Of course, when we think of angels as little more than fat, baby cupids we are bound to dismiss them. These are about as far away from angelic beings as one can get in the Bible. Rather, angelic beings are so awe-inducing and terrifying that whenever they appear to humans they must either tell them to not be afraid (e.g., Luke 2:10) or they must even correct humans who mistakenly try to worship them:

8 I, John, am the one who heard and saw these things. And when I had heard and seen them, I fell down to worship at the feet of the angel who had been showing them to me. 9 But he said to me, “Don’t do that! I am a fellow servant with you and with your fellow prophets and with all who keep the words of this scroll. Worship God!” (Rev. 22:8-9 NIV)

Sometimes angelic beings are even beyond human description. At best, prophets like Ezekiel can describe these spiritual beings’ appearances as like human/animal hybrids shrouded in flame and lightning, or as wheels covered in eyes that can move in all directions:

4 I looked, and I saw a windstorm coming out of the north—an immense cloud with flashing lightning and surrounded by brilliant light. The center of the fire looked like glowing metal, 5 and in the fire was what looked like four living creatures. In appearance their form was human, 6 but each of them had four faces and four wings. 7 Their legs were straight; their feet were like those of a calf and gleamed like burnished bronze. 8 Under their wings on their four sides they had human hands. All four of them had faces and wings, 9 and the wings of one touched the wings of another. Each one went straight ahead; they did not turn as they moved.

10 Their faces looked like this: Each of the four had the face of a human being, and on the right side each had the face of a lion, and on the left the face of an ox; each also had the face of an eagle. 11 Such were their faces. They each had two wings spreading out upward, each wing touching that of the creature on either side; and each had two other wings covering its body. 12 Each one went straight ahead. Wherever the spirit would go, they would go, without turning as they went. 13 The appearance of the living creatures was like burning coals of fire or like torches. Fire moved back and forth among the creatures; it was bright, and lightning flashed out of it. 14 The creatures sped back and forth like flashes of lightning.

15 As I looked at the living creatures, I saw a wheel on the ground beside each creature with its four faces. 16 This was the appearance and structure of the wheels: They sparkled like topaz, and all four looked alike. Each appeared to be made like a wheel intersecting a wheel. 17 As they moved, they would go in any one of the four directions the creatures faced; the wheels did not change direction as the creatures went. 18 Their rims were high and awesome, and all four rims were full of eyes all around. (Ezek. 1:4-18 NIV)

Needless to say, the biblical depiction of angels is awe-inspiring, even dreadful. Is it really any wonder that angelic beings (both good and evil) would be mistakenly worshipped as gods by ancient and modern pagans? C. S. Lewis captures this awe-inducing reality well in his marvelous Space Trilogy of novels. In chapter of 16 of the second novel, Perelandra, the human protagonist, Elwin Ransom, is having a discussion with the Oyarsa of Mars, Malacandra, and the Oyarsa of Venus, Perelandra (in Lewis’s novels, “Oyarsa” is the alien term for archangels that watch over planets). In the course of the discussion they tell Ransom that they must reveal themselves to him in order to better communicate how they will hand over the rule of Venus to a race of unfallen human-like creatures:

“Let us appear to the small one here,” said the other. “For he is a man and can tell us what is pleasing to their senses.” “I can see— I can see something even now,” said Ransom. “Would you have the King strain his eyes to see those who come to do him honor?” said the archon of Perelandra. “But look on this and tell us how it deals with you.” The very faint light— the almost imperceptible alterations in the visual field— which betokens an eldil vanished suddenly. The rosy peaks and the calm pool vanished also. A tornado of sheer monstrosities seemed to be pouring over Ransom. Darting pillars filled with eyes, lightning pulsations of flame, talons and beaks and billowy masses of what suggested snow, volleyed through cubes and heptagons into an infinite black void. “Stop it . . . stop it,” he yelled, and the scene cleared. He gazed round blinking on the fields of lilies, and presently gave the eldila to understand that this kind of appearance was not suited to human sensations. “Look then on this,” said the voices again. And he looked with some reluctance, and far off between the peaks on the other side of the little valley there came rolling wheels. There was nothing but that— concentric wheels moving with a rather sickening slowness one inside the other. There was nothing terrible about them if you could get used to their appalling size, but there was also nothing significant. He bade them to try yet a third time. And suddenly two human figures stood before him on the opposite side of the lake. They were taller than the sorns, the giants whom he had met in Mars. They were perhaps thirty feet high. They were burning white like white-hot iron. The outline of their bodies when he looked at it steadily against the red landscape seemed to be faintly, swiftly undulating as though the permanence of their shape, like that of waterfalls or flames, coexisted with a rushing movement of the matter it contained. For a fraction of an inch inward from this outline the landscape was just visible through them: beyond that they were opaque.

Lewis brings the biblical reality of the terror and awe of angelic beings into fictional prose. What he depicts in his novel directly echoes the biblical realities of angelic beings as great and powerful servants of God, so great that uninformed and fallen humans can easily mistake them for gods. What is even more startling though is that such beings, both good and fallen ones, are active all around us. We see this when the prophet Daniel mourns for three weeks over a vision of destruction. Yet, the heavenly response to such distress was not non-existent, but delayed:

10 A hand touched me and set me trembling on my hands and knees. 11 He said, “Daniel, you who are highly esteemed, consider carefully the words I am about to speak to you, and stand up, for I have now been sent to you.” And when he said this to me, I stood up trembling.

12 Then he continued, “Do not be afraid, Daniel. Since the first day that you set your mind to gain understanding and to humble yourself before your God, your words were heard, and I have come in response to them. 13 But the prince of the Persian kingdom resisted me twenty-one days. Then Michael, one of the chief princes, came to help me, because I was detained there with the king of Persia.14 Now I have come to explain to you what will happen to your people in the future,for the vision concerns a time yet to come.” (Dan. 10:10-14, NIV)

There is obviously some sort of spiritual and cosmic conflict going on in the unseen, non-physical realm of reality here. As Greg Boyd notes in his excellent book, God at War: The Bible and Spiritual Conflict (IVP Academic, 1997):

There is no doubt among scholars that the “princes” referred to here, among whom Michael is “chief,” are spiritual beings who oversee various territories. The account, therefore, depicts some sort of angelic battle that took place behind the scenes of physical reality. Were it not for the revelation given by the angel, neither Daniel nor anyone else would have had any knowledge of this unseen battle.

For the author this behind-the-scenes battle explained the twenty-one-day delay in Daniel’s receiving a response to his petitions. According to this passage, God’s messenger literally got caught up in a spiritual battle that seemed to center on the “prince of Persia” trying to prevent Daniel from getting this message. Were it not for Michael, apparently, Daniel might have been waiting even longer to hear from God.

The whole account sounds unbelievably bizarre to most modern Westerners, who are culturally conditioned to dismiss talk about non-physical conscious beings (angels) as superstition. Such concepts seem to be on the same level as science fiction. Even for modern Christians, who on the authority of Scripture theoretically accept the existence of such invisible beings, this account, for other reasons, sounds incredible.

After all, how many of us believers would consider the possibility of angelic interference as an explanation for why we sometimes do not see an answer to our particular prayers? Or how many of us might seriously consider the possibility of a menacing presence of an evil “prince” over our region as a factor in whether a child is molested, a baby is born healthy or ill, or a group of people accept or reject the gospel? (pp. 9-10)

If you are still reading this post, you are probably asking what the point of all this information is. The point that McKnight, Lewis, Boyd, and others are trying to make is that realizing the reality of the invisible realm is incredibly important for the Christian life. If we ignore, or denigrate as foolish, the reality of non-physical, conscious beings, then we have an incomplete and inadequate Christian cosmology. Rather than being like Rudolf Bultmann and simply dismissing the supernatural elements that don’t seem to mesh with a post-Enlightenment worldview, we instead need to study more critically and deeply about the reality of our “spiritual co-creatures.” I’ll end this already too-long post with a thought from Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics on the matter, which McKnight also quotes in his podcast:

It is true, of course that we can miss the angels. We can deny them altogether. We can dismiss them as superfluous, or absurd and comic. We can protest with frowning brow and clenched fist that, although we might admit that there is a God, it is going too far to allow that there are angels as well. They must be questioned or completely ignored. There are, therefore, even Christian and theological systems in which there is no place for angels. We have to be careful that they are not the very systems in which there is no place for the other constants either. For if we do not know anything of the primary sign and testimony, how can we know anything of the secondary? If we cannot or will not accept angels, how can we accept what is told us by the history of Scripture, or the history of the Church, or the history of the Jews, or our own life’s history? And since it depends upon our acceptance of these secondary signs and testimonies whether or not our own system includes within it the living God, we have to ask ourselves whether a system in which there is no place for angels, and therefore for the primary sign and testimony, will not at bottom be a godless one. Where God is, there the angels of God are. (CD III/3: The Doctrine of Creation, p. 238)