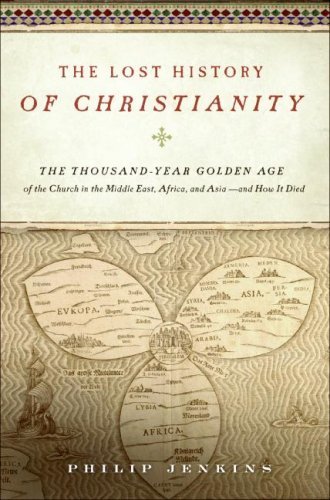

I have been reading a fascinating book over the last several days. Philip Jenkins is well-known for his writing on the topic of modern, Majority World Christianity, especially in regions like Africa, South America, and Asia. His book, The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (Oxford University Press, 2011), is a fascinating investigation into the rapid rise of Christianity in the non-Western world/Global South. Personally, I also find the book quite encouraging. As a confessionally orthodox Christian living in the secular Western world, it encourages me to see Christ’s Church continuing to grow in the world, even if it is not in my own cultural backyard. I look forward to the day when my Asian, Latin American, and African brothers and sisters in Christ come to the West as missionaries. It is a satisfying irony of God that the very people whom modern Western empires all too often oppressed will likely be the means by which future generations of Europeans and Americans find salvation. But I digress.

The actual book that I am reading (and writing here about) is one of Jenkins’ other books: The Lost History of Christianity: The Thousand-Year Golden Age of the Church in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia-and How It Died (HarperOne, 2009). As with most of Jenkins’ work it is illuminating and well-written. However, what differentiates it from so many other “lost history” books is (1) that it is researched and written by an actual, credentialed historian who teaches at a major university (Baylor), and (2) it examines in detail a part of Christian history that most Western Christians have little to no idea about: the non-Chalcedonian Christianity of the ancient Eastern world. As the lengthy subtitle explains, this is the Christianity that existed and thrived in large swaths of the Middle East (in places like modern-day Syria, Jordan, and Iraq), of Africa (places like modern-day Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan), and of Asia (places like modern-day southern India, Uzbekistan, Turkey, Mongolia, and parts of China). While I have known about these Eastern churches (predominantly Nestorian and Jacobite) for some time, I was never really aware of just how established they were in the pre-Islamic world.

Usually, Western Christians like myself tend to think of the trajectory of the early Church in terms of its development in the West. A shocking tautology right? That was sarcasm if you didn’t quite catch it. And make no mistake, I think the development of Christianity in the Catholic-Orthodox world is one of the most important historical developments in human history. Where would we be without the thought of Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Origen, Chrysostom, the Cappadocians, Augustine, Jerome, Boethius, John of Damascus (who actually can fit in both Western and Eastern traditions as Orthodox thinker who lived in Damascus under Muslim rule), Anselm of Canterbury, Albertus Magnus, Thomas Aquinas, Francis of Assisi, Martin Luther, John Calvin, John Wesley, John Henry Newman, C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, etcetera , etcetera, etcetera?

I love the fact that I—as an orthodox, Nicene, Chalcedonian Protestant of Wesleyan, Anglican-ish, and broad patristic persuasion; basically whatever Thomas Oden was—can claim such a rich tradition, even with some of its historical warts. But the fact remains that a whole other Christian world of Africa, Asia and the Middle East existed and thrived for a millennium in the world we now conceive of as almost entirely Islamic. And while I think that the Chalcedonian Definition on Christ’s divine and human natures is essentially correct, the fact remains that the non-Chalecdonian churches of the East still confessed (and still confess) the Apostle’s and Nicene Creeds. Thus they are still Christian brethren, even if we disagree on aspects of Christology. To quote Jenkins directly:

For most nonexperts, Christian history after the earliest centuries usually conjures images of Europe. We think of the world of Charlemagne and the Venerable Bede, of Thomas Aquinas and Francis of Assisi, a landscape of Gothic cathedrals and romantic abbeys. We think of a church thoroughly complicit in state power— popes excommunicating emperors, and inspiring Crusades. Of course, such a picture neglects the ancient Christianity of the Eastern empire, based in Constantinople, but it also ignores the critical story of the religion beyond the old Roman borders, in Africa and Asia. We suffer perhaps from using unfamiliar terms like Nestorian, so that the Eastern religious story seems to involve some obscure sect or alien religion rather than an extraordinarily vigorous branch of the Christian tradition. Only by stressing the fully Christian credentials of these Asian-based movements can we appreciate the abundant fullness and diversity of the global church during the millennium after the Council of Nicea— and the depth of the catastrophe when those movements fell into ruin. Anyone who knows the Christian story only as it developed in Europe has little inkling of the acute impoverishment the religion suffered when it lost these thriving, long-established communities. (pp. 46-47).

While the implications of this are very far-reaching, two of the most notable aspects for me include the emphasis on intellectual scholarship in Eastern Christianity and the guidance on the canon of Scripture. Regarding the topic of intellectual achievement in ancient Christianity, there is often a popular (but false) sentiment that Christianity squelched the cosmopolitan and learned culture of the ancient pagan world. While this is quite untrue even when limiting our view to the Latin West (see my previous post), if one had any doubt about the matter, a look at the commitment to learning, scholarship, and the preservation of classical texts such as Aristotle in the Eastern Christian world would settle the matter. Indeed, as Jenkins argues, the preservation of classical texts that were later reintroduced to the West and led to the Renaissance, via interaction with the Islamic world, is largely thanks to Eastern Christian scholars! Here is Jenkins on the matter:

Syriac scholarship found its primary home in Nisibis, which by the sixth century had developed a school that was the closest the Christian world possessed to a great university, a worthy successor to the academies of ancient Greece. Persia’s Sassanian kings favored this school, together with a counterpart at Jundishapur, which became a refuge for dissident Christian scholars uncomfortable with Byzantine rule. The fame of Nisibis spread around the world, supplying a model for the pioneering Latin Christian scholar Cassiodorus in far-off Italy. It was at Nisibis that much of the ancient world’s learning was kept alive and translated, making it available for later generations of Muslim scholars, and for Europeans after them. Among other classical works, Nisibis preserved the writings of Aristotle and his commentators. In 1026, Nisibis was the scene of a famous debate between the Nestorian bishop Elijah and a Muslim vizier. Arguing for the superiority of Syriac over Arabic, the bishop made the seemingly incontestable claim that Arabs had learned most of their science from Syriac [Christian] sources, while the reverse had seldom occurred. (p. 77).

In addition debunking to the myth of inherent Christian anti-intellectualism (again, proven wrong by the fact that it was Greek and Eastern Christian scholars who kept such learning alive for hundreds of years before the rise of Islam and the texts’ reintroduction to the Latin world), a survey of Eastern Christian biblical commentators helps us to debunk a prevalent cultural myth about the formation of the biblical canon. Thanks to pop historical fiction like the DaVinci Code the idea that Constantine ordered a New Testament canon formed at the Council of Nicaea in 325 A.D. that supported his power holds popular sway. Now, any actual historian, Christian or otherwise, will quickly point out that the Council of Nicaea had absolutely nothing to do with the canonization of Scripture. It was all about the nature of Christ’s divinity. But actual history has never stopped the Dan Browns of the world. Even further, most scholars will tell you that the bulk of the New Testament canon had been unofficially put in place by the end of the 3rd century, well before the Constantine came along. However, if one still had doubts about the influence of political wrangling in the formation of the Christian canon, you need only look at the Eastern Christian world for clarification on the matter:

The Syriac Bible [the Peshitta] was a conservative text, to a degree that demands our attention. In recent years, accounts of the early church claim that scriptures and gospels were very numerous, until the mainstream Christian church suppressed most of them in the fourth century. This alleged purge followed the Christian conversion of the emperor Constantine, at a time when the church supposedly wanted to ally with the empire in the interests of promoting order, orthodoxy, and ecclesiastical authority. According to modern legend, the suppressed works included many heterodox accounts of Jesus, which were suspect because of their mystical or even feminist leanings.

The problem with all this is that the Eastern churches had a long familiarity with the rival scriptures, but rejected them because they knew they were late and tendentious. Even as early as the second century, the Diatessaron assumes four, and only four, authentic Gospels. Throughout the Middle Ages, neither Nestorians nor Jacobites were under any coercion from the Roman/ Byzantine Empire or church, and had they wished, they could have included in the canon any alternative Gospels or scriptures they wanted to. But instead of adding to the canon, they chose to prune. The Syriac Bible omits several books that are included in the West (2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, Jude, and the book of Revelation). Scholars like Isho’dad wanted to carry the purge further, and did not feel that any of the Catholic Epistles could seriously claim apostolic authorship. The only extraneous text that a few authorities wished to include was the Diatessaron itself. The deep conservatism of these churches, so far removed from papal or imperial control, makes nonsense of claims that the church bureaucracy allied with empire to suppress unpleasant truths about Christian origins. (pp. 87-88).

Needless to say, the Eastern Christian world was a vibrant and developed world that we all to often forget about. Not only does a book like Jenkins’ help counter the claim that Christianity is really just a “Western religion” (from the very beginning, Christianity was a diverse and expansive faith), it also helps us to see a major part of Christian history that is often unknown and obscured to us. It is a lost history that deserves to be found anew.