On the eve of Holy Week, I’m noticing the ho-hum way Mark’s triumphal entry account concludes. Let’s call it the paradox of the palms.

“Then he entered Jerusalem and went into the temple; and when he had looked round at everything, as it was already late, he went out to Bethany with the twelve” (11:11).

A bit of an anti-climax, after all the hosannas.

Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem is a strange story. Its significance isn’t quite clear in either the gospel telling or in the liturgical reenactment that we call Palm Sunday. Christians have integrated the rest of Holy Week into our faith language. But for the celebratory trip through the city on a donkey colt we have no corresponding theology.

Possibly because it seems superfluous. Is this a story about the victorious Jesus? We’ve got Easter for that. Is the donkey about humility? Good Friday gives us that image much more clearly. Perhaps it is Jesus sharing of himself with all of us? That’s Maundy Thursday. What then, do we do with the palms?

The Messiah We Never Expected

The point, I think, is the ambiguity itself. This is the Davidic Messiah, the awaited one. That’s something all the ancestors hoped for, and certainly worth celebrating. But what does it mean to expect something like that? If hoping is Israel’s faith, how do you integrate hope’s end? The awkward anticlimax suggests that dilemma to me. The long awaited one looks around the temple and says, “well, it’s getting late, so….”

This “what now” moment has been Israel’s story from the beginning. Think of Noah after the flood, or the Tribes after crossing the Red Sea or, after that, the Jordan. The floods have receded. Our enslavement and nomadic years are behind us at last. Do we … take some moonshine into our tent to celebrate? Start complaining about the food? Look around and notice the time?

Fulfilled hopes require ongoing curation. A consistent attempt to narrate the new revelation into the old story. That’s because the triumph of God is never quite what we expected it would be. This is, I think, the lesson of Palm Sunday. The paradox of the palms is the foreshadowing of the whole paradoxical story that Holy Week is going to tell.

The Paradox of the Passion Week

We make a mistake, theologically, when we separate out triumph and defeat in the Passion narrative. This is a typical evangelical mistake, though others make it as well. It’s visible in Passion Plays especially, when the resurrection looks like an erasure of the cross. Good Friday then becomes a kind of queen’s sacrifice. It only looks like humble obedience to death. In fact, that’s all a ruse, meant to distract, so the real glory can explode.

That theology is, if you’ll permit a bit of jargon, a soteriological version of the Christological heresy of docetism. It is, I mean, a problematic way of talking about Jesus, now transferred into a problematic way of talking about salvation. Docetism is the heresy that insists that the humble embodiment and suffering of Jesus is ephemeral; what’s real is his powerful divinity. Similarly, an Easter white-out of Good Friday can end up saying that humble obedience to death is for wimps and losers.

But Jesus’ triumph is always strange. Easter morning in the gospels is about a missing person more than it’s about an ultimate win. And when he shows up, it’s his familiar voice and his scars that idenitify him.

Christus Triumphans

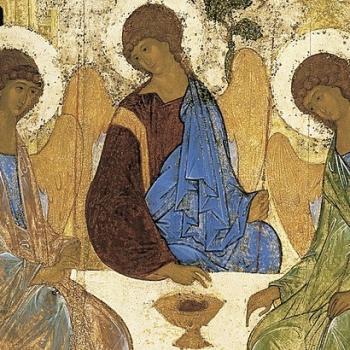

Eastern icons of the cross often show the way this paradoxical victory carries through Holy Week. The cross is already a victory, if a complex one. Orthodox theologian Vigen Guroian notes the way, in a tradition of iconography called Christus Triumphans, “the resurrection shines through the crucifixion.” Notice, in the image atop this blog, how the crossbeam behind Jesus’ arms also serves as the opening darkness of the tomb. The cross is already an empty tomb.

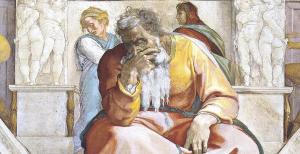

But if the cross is already a victory, the resurrection remains a passion. I think that’s the unexpected reveal of Palm Sunday. We are right to wave palms with the Judeans. There’s everything to celebrate here. But we’re headed for a shocker. It’s not the victory we imagined. It’s more like the ecstasy that Moses finds atop Sinai. God’s glory as the thick and heavy presence of a cloud. To paraphrase Gregory of Nyssa: Easter is not when the darkness of Friday disappears; it’s when it turns luminous.

The empty tomb is itself a darkness. That’s what the dark of Good Friday—and perhaps even of the “late hour” of Mark’s Palm Sunday—become. It’s good darkness. Mysterious darkness rather than the dark night of death and sin. But it is still as dark as Sinai. At least that dark.

Maybe the ultimate lesson of the paradox of the palms is that we confuse the issue if we think divine humility and divine victory are different moments. As Dionysius might have put it, we celebrate a God who is beyond the contrast of triumph and defeat. A God whose crown is made of thorns. But equally: a God on whose head all thorns become a crown.