What follows is an excerpt from my own recently published work, The Papist’s Guide to America. I’m posting it here because, although I meant it as a defense of the Magisterium in general, it may also serve as a thorough defense of Pope Francis’s powerful new document, Amoris Laetitia.

The thesis is simple: that the same pastoral logic which necessitated Vatican II also necessitates Amoris Laetitia, and that, because of this causal identity between the two, we should expect that those who could not comprehend the logic of the former will be just as confused by the logic of the latter.

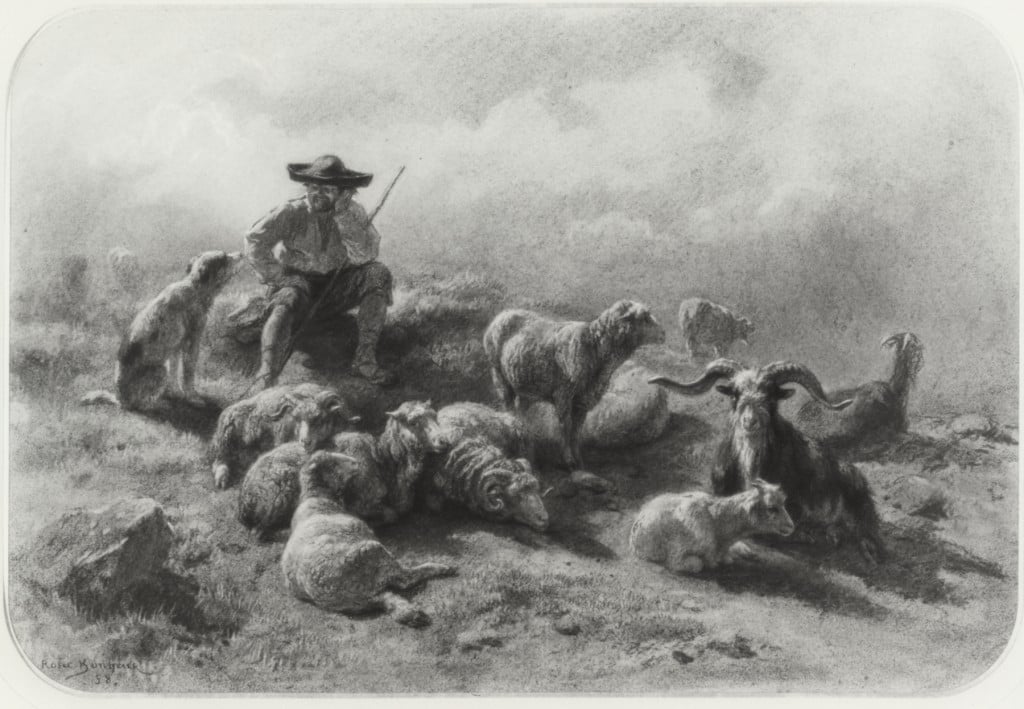

There are many devout people, it seems, who think of the Church as purely transcendent, an ideal which has no good reason and certainly no need to descend into the darker, dirtier areas of earthly life. They would have the Good Shepherd sit on a hilltop, preaching his principles and shining his light for the world to see.

But the problem is that sometimes the sheep leave the hilltop. If this happens, and if the Good Shepherd insists nonetheless on remaining where he is, refusing to leave the comfort of his lofty, sunny, perch in order chase the lost sheep into the mire, then he is not a Good Shepherd at all. Didn’t Jesus Christ who come first and foremost to recover the lost?

This selection picks up after a discussion of liberalism (economic, political, religious), and at the point in a larger historical narrative at which the liberal revolution had achieved its success, taking center stage in Western world…

—-

To say that this revolution changed man to his core—that it modified the way he sees Truth itself—sounds a bit drastic. Yet consider the way in which we imagine, or, more accurately, are no longer capable of imagining, traditional concepts such as heresy.

Heresy, from an etymological standpoint, means nothing more than “to choose for oneself.” Obviously, then, the word is entirely appropriate for one who departs from orthodoxy to blaze his own trail. Heresy, then, implies the existence of orthodoxy, which is its counterpart. In the past, every heretic believed himself to be orthodox. The two terms are related to one another, in the same way that “to be inside” of something implies the existence of an “outside.” But with Liberalism something altogether new was introduced to man. It was a heresy, to be sure, but for the first time it was a heresy that made no pretenses at orthodoxy. It was, in fact, the first heresy to more or less explicitly reject orthodoxy as a valid conception. And because orthodoxy signifies those beliefs which are true, to render it invalid is to render incomprehensible the traditional notions about truth and error.

To quote from Fr. Sarda’s Liberalismo es Pecado:

“Liberalism…transgresses all commandments. To be more precise: in the doctrinal order, Liberalism strikes at the very foundations of faith; it is heresy radical and universal, because within it are comprehended all heresies…”[1]

“It repudiates dogma altogether and substitutes opinion, whether that opinion be doctrinal or the negation of doctrine. Consequently, it denies every doctrine in particular. If we were to examine in detail all the doctrines or dogmas which, within the range of Liberalism, have been denied, we would find every Christian dogma in one way or another rejected—from the dogma of the Incarnation to that of Infallibility.”[2]

But Fr. Sarda will not leave his analysis incomplete. The explicit denial of the legitimacy of dogma carries with it an implicit affirmation of a “new dogma” which is both universal and negative in its character:

“Nonetheless Liberalism is in itself dogmatic; and it is in the declaration of its own fundamental dogma, the absolute independence of the individual and the social reason, that it denies all Christian dogmas in general. Catholic dogma is the authoritative declaration of revealed truth—or a truth consequent upon Revelation—by its infallibly constituted exponent. This logically implies the obedient acceptance of the dogma on the part of the individual and of society. Liberalism refuses to acknowledge this rational obedience and denies the authority. It asserts the sovereignty of the individual and social reason and enthrones Rationalism in the seat of authority. It knows no dogma except the dogma of self-assertion. Hence it is heresy, fundamental and radical, the rebellion of the human intellect against God.”[3]

The victory of liberalism meant the extinction of the concepts of both heresy and orthodoxy, which really represented nothing more than the primordial duality of truth and falsity. The old positive-negative pair was then replaced with a single, universal negative which rendered the previous paradigm illegitimate and, further, assured that anyone indoctrinated into the negative dogma of liberalism would be completely unable to understand the old terms. Man was left to sit alone in the privacy of his home, asking with Pilate “What is truth?”[4]

Vatican II and the New Era

The Gates of Hell will not prevail against the Church, but we’re given no guarantee that the Church will prevail in every single battle. In the words of J.R.R. Tolkien, we are engaged in “the long defeat.” This puts the Church in an interesting position. The Apostles were instructed that, if rejected, they should shake the dust from their feet and move to the next city; but the Church may never do this. Her assigned city is the world. She is with man until the end, for that is her entire purpose. So what is the proper course?

The Church is an expert in humanity.[5] She is its physician, and a responsible physician, if he senses the danger of disease or infection, does everything he can to warn his patient of the threat. Ideally speaking, his advice will be heeded (he is the expert, after all) and the patient’s health will be maintained. But sometimes, as we all know from our own experiences, the patient disregards his doctor’s advice and contracts the disease in spite of the efforts of his adviser. In this case and at this point, his doctor will accept this change in conditions and readjust his treatment. We would call him obstinate, ineffective, and even unwise if he did not make this change, for the disease has now set in and this requires advice of a different kind. The patient is diseased. The physician must treat him accordingly, and no amount of lecture about what he could have done to prevent the infection will be of any use to anyone: that course is not currently open to either party.

To put it another way, the Good Shepherd does everything he possibly can to keep his flock together. However, should the wolves scatter the sheep, he will, if he is indeed the Good Shepherd, travel far and wide to recover those who have wandered away. If they have wandered into the desert, the bog, or the forest, he goes there, and he goes not because he wishes it or because he enjoys the bog, but because that is where the sheep have gone.

We must keep this in mind as we approach the most significant Magisterial result of the Liberal revolution: The Second Vatican Council. Also called Vatican II, this event was nothing more or less than the decision of the Church to enter the bog of modernism, so to speak. Like the Good Shepherd and the Good Doctor, she chose this path not because it was good, but because Her vocation required it.

Formally opened by Pope John XXIII on October 11, 1962 and closed under Pope Paul VI in 1965, this twenty-first ecumenical council of the Church was precisely the sort of action described above. The Church had made every effort to administer preventative treatment and curb the infection at its source. It had made war on man’s behalf for over 100 years on the Liberal contagion, but to no avail. Western Civilization was now diseased, and so a new form of counsel was necessary.

It is important to remember what was said earlier regarding concepts like “orthodoxy” and “heresy,” that they had been rendered incomprehensible to the modern man. A person born and raised in the Liberal context cannot understand why he must believe something any more than why he must not. Everything must pass through the lens of “freedom” which is the only discerning lens his cultural training provided him with. This ensures that those old notions do not compute.

Sensing this, the Church called together its best physicians from around the world in order to discern the idiosyncrasies of man’s new condition—in body, mind and soul. How has he fared throughout the revolution? In what ways has he been affected? What are his symptoms? And what sort of treatment can best bring him back to health?

Continuity and Renewal

Before we discuss the actual outcome of the Council and the responses it provoked, something must be said for the nature of the Church’s mission.

The Church is tasked with protecting the eternal and unchanging teachings of the Church, but at the same time she must provide appropriate adaptations, and, when necessary, re-adaptations, for each society and historical period. The Church must “become all things to all people,” and this means that when a new epoch presents itself, altering custom, language, and thought, it is up to the Church to make sure that the presentation and application are still true to the Tradition. This necessitates that the Church adopt a twofold method in regard to its message:

On the one hand it is constant, for it remains identical in its fundamental inspiration, in its “principles of reflection,” in its “criteria of judgment,” in its basic “directives for action,” and above all in its vital link with the Gospel of the Lord. On the other hand, it is ever new, because it is subject to the necessary and opportune adaptations suggested by the changes in historical conditions and by the unceasing flow of the events which are the setting of the life of people and society.[6]

The Church speaks with a voice that is “consistent and at the same time ever new.”[7] This is absolutely not a question of relevance. Relevance comes down to a matter of whim and attempts to achieve it often amount to self-compromise and an appeal to changing whims. The Church does not sacrifice at that altar.

It is a question of distinguishing principles from their concrete application: Principles are unchanging and eternal, but a particular application of a principle may not be appropriate for each and every historical circumstance. The Sun casts light on a different portion of the earth’s surface every hour; but does this mean that the Sun is on the move? On the contrary, it is we who are constantly in flux, and if the Light of the Church appears to alter itself, it is only in accordance with the inconstancies of the world. Loud and clear it must be proclaimed: when the Church demands something which appears different today than what it asked yesterday, this should not be taken as contradiction—much less should it be assumed that the Church is “admitting error” and “correcting its mistakes.” It is simply evidence for us of a changing world. More importantly, it is proof of a Living, Teaching Church.

Outcomes of the Council

By the time the doors closed on Vatican II, the members had produced four constitutions, three declarations, and nine decrees. Each of these has its purpose, although opinions seem to vary as to the exact significance of each. What is generally acknowledged, however, is that their doctrinal significance is hierarchical, with the constitutions acting as the most binding of the three, while the remaining two categories are of less gravity, aimed at addressing certain specific concerns or acting as appendices to a constitution.

We cannot go into depth here on each document that was produced, so instead we will mention only the declaration Dignitatis Humanae, which turned out to be one of the most divisive of the collection. It therefore serves as an appropriate illustration for us, because the arguments presented for or against it tend to be representative of the entire debate regarding the Council.

Dignitatis Humanae has generated a great deal of argument and debate for such a concise document. It is only a few pages long, so the reader cannot be excused from obtaining a copy for examination. This document, called the “Declaration on Religious Freedom,” addresses the relationship between the Church and modern states, as well as between modern states and the individual.

In brief, the document states that “all men are to be immune from coercion on the part of individuals or of social groups and of any human power, in such wise that no one is to be forced to act in a manner contrary to his own beliefs, whether privately or publicly, whether alone or in association with others, within due limits.”[8] But its authors take care from the first paragraph to say that this document “leaves untouched traditional Catholic doctrine on the moral duty of men and societies toward the true religion and toward the one Church of Christ.”[9]

Now it is understandable that those who have read and treasured the encyclicals of Leo XIII and predecessors would be at first confused at these two statements placed right next two each other. After all, we find there that “the State, constituted as it is, is clearly bound to act up to the manifold and weighty duties linking it to God, by the public profession of religion…it is a public crime to act as though there were no God. So, too, is it a sin for the State not to have care for religion as something beyond its scope, or as of no practical benefit.”[10] Does the declaration of Vatican II contradict this saying?—and, if so, which is the faithful Catholic to accept?

But at this point we must marshal before us what was said above: that the whole purpose of Vatican II, and any other council for that matter, was to provide at the same time continuity and renewal of the unchanging truths of the Christian Tradition. It is entirely superficial to read the anti-Liberal documents of the warrior popes such as Leo XIII and the three Piuses in precisely the same fashion and from the same point of view as the documents of Vatican II. Remember the role of the physician before and after the disease has set in: Leo XIII was trying, until the very last moment, to prevent the spread of the infection. He was trying to save the progression of the illness from entering a new stage. He and his predecessors did not succeed. So be it. The illness spread through the world and changed its character entirely. The good physician, tender and faithful, convened the Council in order to reassess and formulate the new treatment.

In its assessment, the Council found that it now existed on the outskirts of secular societies, individualistic in mentality, obsessed with rights, and largely unable to comprehend older notions. In this light, we must look again at the documents of Vatican II. Isn’t it clear that they are nothing but the unchanging doctrines of the Church specifically adapted for application within individualistic, secularized, rights-based societies.

In the past, when the Church was an institution intimately integrated into every level of social life, there was no danger of intolerance. The Church, in fact, was a bastion for religious freedom, despite the myths now spread about Inquisition and witch-hunts—convenient for secular states who are always trying to justify themselves. But Leo’s prophecy about the implicit atheism of secularized governments had come to pass, and so the emphasis of the Church’s message had to change along with the reality. A change in emphasis does not imply contradiction, but rather it displays its dynamism.

Because modern nations had become secular, man had to be protected from the State in his worship in a way that was never quite necessary before. The Church also had its own freedom threatened. This called for specific and new emphasis on religious liberty—hence the Declaration on Religious Freedom. Nothing was nullified, and what was declared in the past remained truth. Following the example of Christ, the Church preaches the truth, asks for perfection, but when man falls short, is always prepared to come minister to his wounds wherever he happens to be.

If we laid the entire collection of anti-Liberal documents right next to those produced during Vatican II—even Dignitatis Humanae—it is entirely possible to imagine that they were written by the same hand. All that we need in order to connect them and render their statements comprehensible is to imagine the following statement inserted between the two collections: “In the event that all of our warnings are ignored, and the worst should come to pass, see below:”

If every application of Church teachings “in the here and now” is contingent on present conditions, Vatican II was but the development and implementation of a new contingency plan.

Reception and Division

If we divided Catholics into groups based on their responses to the Council, we would come up with two: those who paid attention, and those who did not.

Of these, the second group comprises the vast majority of the laity. One of the unique aspects of the new era was that councils, synods, proclamations, declarations, exhortations, any other “official” actions of the Church ceased to matter to the man on the street. Just as the Church itself had been rendered as irrelevant to his daily routine, so also were the messages which issued from Her. Thus, the vast majority became insulated from the words of the Magisterium not by overt censorship but by the unconscious complacence that secularism instills. This left them to continue about their business without taking much notice of the whole affair.

But what of the other group?—those who were “waiting at the door” of the Council chamber, eager for its outcomes? These we can also divide again into two groups, based on whether their response was positive or negative. Yet that would not be sufficient, because on a very deep level both classes of reaction were evidence of a violent pessimism toward the Church Herself. What I mean is this:

Those who responded positively toward the new posture and plan of the Church, embracing the new emphasis of documents such as Dignitatis Humanae seemed, in general, to believe that this marked a departure from previous teachings. They seemed to believe that the new contingency plan was not that at all, but was instead an admission of the Church’s previous “backwardness” and that the Council had finally led the Church to “come around” to the truths of progress and Liberalism. And so this sort of response, although positive, is more accurately a sort of positive pessimism because it implies that the Church and its leaders, who worked so hard on behalf of man, had been laboring in vain all through the great war. It insinuated that the Church had been “on the wrong side of history.”

Those who responded negatively to the outcomes of the Council held an opposite view which we can call “negatively pessimistic.” They essentially agreed with the others that the Council represented not only a shift but a discontinuity in Church teachings. They only differed on which historical period they chose to reject: unlike their opponents, they sided with the warrior popes and rejected Vatican II, its participants, and its documents as heretical.

Neither of these two responses (whether a positive pessimism or a negative pessimism) seem to allow the possibility that it was not the doctor who changed but the patient. Neither seemed to be able (or perhaps, willing?) to give the Church the benefit of the doubt. The docility demanded by the Church is, it seems, one of its most difficult teachings.

And so, although there are no doubt many faithful Catholics who do not align with these general categories, the closing of the Council was met with two responses: indifference and pessimism. Coincidentally, both of these attitudes can be interpreted as symptoms of Liberalism, which can be expected to manifest itself differently according to the personality and disposition of each individual.

The Church is a prudent mother. She discerns when it is time to talk about something else. There is truth in the scriptural wisdom about throwing “pearls before swine.” You aren’t helping anyone by tossing them precious gems if their present condition prevents them from either appreciating or understanding the value of such things. The good shepherd feeds his flock—that was the mandate given to Peter. That is the task which concerns his successors. There may come a day when pearls—things of loftier value—are once again appropriate, but that is not today.

[1] Liberalismo es Pecado, Fr. Felix Sarda y Salvany, ch. 3.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] John 18:38.

[5] Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church, 61.

[6] Sollicitudo Rei Socialis, 3.

[7] Caritas in Veritate, 12.

[8] Dignitatis Humanae, 2.

[9] Ibid., 1.

[10] Immortale Dei, 6.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons