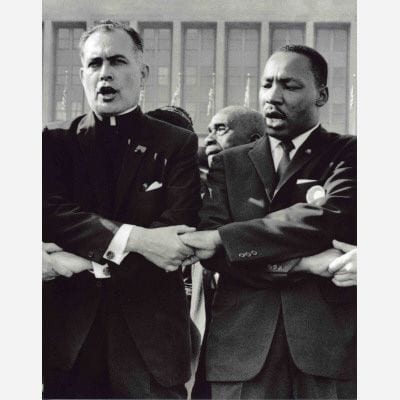

Image via www.nd.edu

What year are we living in — or reliving? That is, what year of recent history?

I’m thinking of the way we’re struggling to understand this moment by comparing it to other times of change and unrest, several of which I lived through myself.

A popular pick, it appears, would be 1968, a year of protest and uprising (against the war in Vietnam and in reaction to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.), including riots in 110 cities, probably the greatest wave of civil unrest since the Civil War. I was a senior at UT Austin and had received the initial letter warning me an official draft notice would be coming.

I would argue that 1968 is a less valid choice than 1965, allowing for the fact that these moments are not really comparable at all. Still, here’s my reasoning.

Tragically, the violence and destruction of these last few weeks since the George Floyd murder have descended on innocent citizens and their businesses, despite calls from all sides to avoid such nihilism. In the first weeks of protest, these episodes were fully reported by the media, the images of looting and burning in broadcast loops for hours and days on end. If you knew nothing much about 1968, you might almost think the two outbreaks were comparable in scale. They are not.

Moreover, we are no longer seeing the destruction of stores. Instead, some groups have turned to pulling down and defacing statues, a kind of civil action which has the odd side-effect of generating conversation about the actual histories of the men so memorialized. We do not easily reconsider this settled history, so it can be a shock for some to discover Grant’s role in the Indian Wars or former Philadelphia mayor Frank Rizzo’s views on race and policing.

Very few Southerners today believe that a good way to understand their region’s history is through public sculpture erected by white supremacists in order to celebrate the Confederate cause.

In my own small Indiana town, our Black Lives Matters protest at the courthouse turned out to be an inter-faith, inter-racial prayer vigil, wholly peaceful. In a neighboring town, two Black and white organizers held a similar event at which they publicly washed each other’s feet. Until the media likely got bored with the angle, stories of peaceful protest in unlikely Red State American smalltowns were everywhere. White pastors were sometimes involved, but not evidently to the degree they were in 1965, a year of unrest which also represented an upwelling of hope among many Black and white Christians of various backgrounds.

My theologian friend Holly Coolman posted a comment on her Facebook page recently, urging, “What matters is that we recognize the depth of the challenge and live out the truth that Black lives do matter, linking arms with whomever we can, in whatever way we can, to honor that claim and to move toward a reality that reflects it fully.”

I’m afraid many in the white Christian universe — those over 40, say — grew tired of linking arms over racial justice years ago. Maybe they feel the issue is insoluble. Or possibly, they believe, as some claimed in 1965, the risks of social change — which are always unknowable, as Hannah Arendt has taught us — are simply too high. We have a debt to pay here, they acknowledge, but we can no longer afford to pay it. Not quite yet. There’s the pandemic. And we should restart the (old) economy first.

Meanwhile it is hugely inspiriting to see Black leaders — including especially pastors — apparently watching a different social process underway, and on a global scale. “This time is different,” they say, appearing almost nervous about acknowledging the possibility of hope after a half-century of decline for black families in every measure of well-being. The difference this time is the solidarity across every line of color and class, as well as the sheer scale of the protests against a shared sense of systemic injustice. And the sense of reconciliation.

As in 1965, most white Christian churches — certainly including the Catholics — are absent from whatever this moment is creating. If Rev. William Barber is possibly the most visible Black faith leader of the current moment, his coalition includes only a relative handful of allies representing white churches. But that absence is an indicator of the sad condition of American Christianity. Let us hope its non-witness will not doom this unimagined leap toward a more racially just society in a time of great awakening.

As Thomas Merton once wrote to Fr. Dan Berrigan, “Don’t be discouraged. The Holy Spirit is not asleep.”