Chances are, if you follow national and international news at all, you’ve heard or read about evangelicals. The presidency of Jimmy Carter, a self-proclaimed “born again” Baptist, brought the term into popular American vocabulary. And so began decades of understanding evangelicalism through a quasi-political lens.

What is Evangelicalism?

But evangelicalism is historically a name for a particular brand of Christian faith made popular in America during the 18th century. In recent years, theologians and church leaders have attempted to refine its definition, reaching back into history to examine how early adopters of the term used it. Defining an evangelical by theology more than by activities, the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) collaborated with Lifeway Research to offer this four-point outline of evangelical convictions. An evangelical affirms:

- The Bible as the highest authority for belief

- Jesus’s Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection as sufficient for salvation

- A belief that people need to trust in Jesus alone for their eternal destiny

- The need for believers in Jesus to share their faith with others

With the NAE definition in mind—rather than the current political/activistic/racial/beliefs characterization—let’s explore a (very incomplete) selection of “who’s who” of evangelicals throughout (primarily) American history.

Early Days

Any semi-respectable overview of famous evangelicals must begin in England, where the movement began to take shape.

John Wesley (1703–91)

An English evangelical clergyman, preacher, and writer, Wesley (accompanied by his musically-inclined brother, Charles) founded the Methodists. While a student at Oxford, he joined a group of friends called “the holy club,” in which members prayed, attended church, and served prisoners and the needy. He traveled to the colony of Georgia, where he met and was influenced by Moravian missionaries, whom he kept up with upon his return to England. At one of their services he professed faith in Christ, trusting him alone for salvation.

Already an ordained minister of the Church of England, he soon began what would be a fifty-year itinerant preaching career. Groups of new believers organized into small groups that eventually had to split from the Anglican church (which was none too happy with Wesley). He emphasized moral living, self-discipline, and thrift—virtues that contributed to England’s relative social peace (when France and the American colonies endured revolutions). Wesley’s influence remains strong within Methodism and Wesleyanism.

George Whitefield (1714–70)

Whitefield met the Wesley brothers while he was a student at Oxford. He became an Anglican deacon, demonstrating his extraordinary stage talent whom thousands sought out when he arrived to preach. Though based in Great Britain, he traveled seven times to the American colonies, as well as dozens of trips to other European countries, for preaching tours.

In 1739, his first major tour of the American colonies began in Philadelphia. The crowds that came to hear him were so large he was required to take them outdoors. A Calvinist in theology, he focused on the necessity of conversion, which he called “new birth.” He also preached to slave populations, which scholars believe led to the development of the rich African-American Christianity.

His preaching tour of 1739–40 gave rise to the spiritual revival known as the Great Awakening. The itinerant preacher was a household name, drawing great crowds everywhere he went. He died at age 55 in the colonies the morning after a sermon.

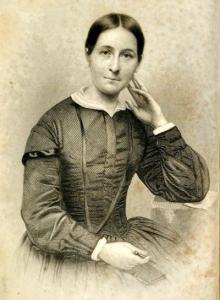

Phoebe Palmer (1807–74)

A Methodist who loved the Lord, Phoebe sought an emotional confirmation of her salvation but came to understand that the emotional experience wasn’t necessary—her belief was effectual for her salvation. She began to organize weekly prayer meetings, which grew into opportunities to teach, write, and preach. Working-class folks of the mid-19th century wanted to regain the “first love” of their conversions, to continue to feel an intimate, powerful connection to the Lord. Palmer and other Wesleyans, among others, preached that if a person devoted oneself entirely, trusted the Bible’s promises that they had the Spirit’s empowerment to live a holy life, and asked for the grace to live that life, then a person could experience “entire sanctification” or holiness of heart and life.

Palmer’s ministry led to what we know now as Pentecostalism, so she is considered the mother of what became the holiness movement.

Dwight L. Moody (1837–1899)

An evangelist and revivalist in the late 1800s who helped usher in a spiritual awakening in America. He is considered by some to be the greatest Christian evangelist of the 19th century. A Massachusetts boy, Moody was schooled only to the equivalent of 5th grade. He even failed the doctrine exam when he tried to join a Congregationalist church at age 18. He remained an informally educated man but grew into one of the greatest preachers of the 19th century. A successful shoe salesman, he accepted Christ as his savior, then moved to Chicago where he began ministering among the poor. In 1858, Moody established a mission Sunday school which eventually became a church.

In the 1870s he led evangelistic crusades to the British Isles and throughout New England before turning his attention to education. Returning to Chicago, he founded a Bible institute (which now bears his name) so that everyday folk like himself could learn the Bible more fully and, in turn, spread the gospel far and wide.

He was well-loved as a family man, devoted to his wife and their three children.