By Dr. Kate Kingsbury† and Debra Van Neste*

Since time immemorial religions have been born from the random rencounters of disparate doxa that have syncretically intertwined to create new modes of believing, belonging and being in our world. Vodou is one such religion, whose roots are an entangled skein of myriad origins. Primarily the faith’s principal provenance may be traced to Africa, yet Vodou has also been critically contoured by Catholicism. Only once we understand how cocktails of convictions create new religions, can we comprehend how the Black Madonna became a Vodou Spirit.

A Racist Myth: the Satanic Savage

Catholicism was imposed upon the New World by the French colonists and Iberian conquistadors. European missionaries proselytised with the paternalistic promise to ‘civilise the savages’ and deliver them from the evils of their own indigenous beliefs, which according to Darwinian tropes in time at that place, held back their evolution. Furthermore, according to the racist ideology prevalent in that zeitgeist, Christians asserted that local spiritual beliefs had at their fulcrum diabolical deities and satanic forces that would only lead to iniquity and debauchery. They must be eradicated.

Notwithstanding this, conversion to Christianity did not inhere locals merely ‘uploading’ Christian beliefs and rituals as a carbon-copy. Christianity was reinterpreted by local populaces, such as African slaves and other indigenous peoples, along the lines of their own pre-existing religious traditions.

Vodou Visions : a New Faith in a New World

In the 18th century slaves from Africa were forcibly brought to Haiti by the colonial powers to work on the plantations thereby providing dirt-cheap labour for their white masters. Many slaves were brought from Dahomey (Benin), Ghana, Senegal, the Gambia, Nigeria, Angola and the Congo. Although stripped of their family, roots and homeland, these slaves retained the complex cornucopia of beliefs and rituals that had at its fulcrum indigenous spirits -often related to nature and the elements- ancestor worship and possession by spirits.

Those from Dahomey practised Vodun, which although the grandparent of Vodou, is not exactly the same. Albeit, it is incontrovertibly evident that Haitian Vodou, much like its older parent, consists of a polytheistic pantheon of spirits and divine elements that reign over the cosmos.

Upon arriving in the colony these slaves formed a new multicultural community, even conjoining with the few Taino Amerindians that remained after the decimation by Christopher Columbus’ men. And the congeries of spiritual ideas coalesced to form Haitian Vodou. This faith and its rituals indubitably offered the captives respite and succor as they sought solace and agency, invoking spirits, known as Lwa, to cope with the egregious conditions imposed upon them by their white masters and violent atrocities to which the colonisers subjected them to on a daily basis.

The French, afraid of these seemingly ‘savage’ beliefs and ‘wild’ rituals forced the slaves to convert to Christianity. This concatenation of events led to a cultural cooking pot where different religious registers syncretically synthesised and symphonised. Due to the imposition by the French of Catholicism, the religious arras that is Vodou was added to with Christian colours that entangled within the webs of other interwoven threads came to take on new meanings and impel neoteric modes of worship.

Vodou Spirits: Lwa

A Lwa in Haitian Vodou is a spirit. There are numerous Lwa, they are also known as ‘mystères’ or ‘invisibles’. Lwa are spirits who serve as intermediaries between the Supreme Creator, Bondye (from the French word Bon Dieu, the ‘good Lord’) who is a distant figure that cannot be propitiated as Lwa can. Lwa aid human beings in their daily affairs and occasionally carry messages from the dead. Each Lwa has its own distinct persona, specific dances, songs and tastes for particular worldly items. They also have their own vèvè, or ritual drawing which may be used to summon them. Lwa must not merely be prayed to, a Vodou practitioner must make sacrifices to influence the spirits and enter into rapports of reciprocity with them so that petitions will be looked upon favourably. Practitioners are also regularly possessed by them during rituals, enabling them to take on the characteristics and powers of that Lwa so that the mysteries may be spoken.

The Black Madonna becomes a Lwa

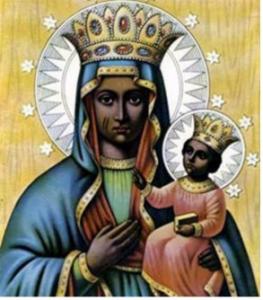

Images of the Black Madonna were brought to Haiti by Polish mercenaries. The latter fought on both sides of the 1802 Haitian Revolution. Indeed, the Vodou religion played an integral role in inspiring the first and only successful mass slave rebellion, which resulted in the establishment of the world’s first Black Republic and the birth of the second nation of the Americas in 1804. The Black Madonna became incorporated into the Vodou pantheon of Lwa.

Upon encountering the image, Vodou practitioners identified with this powerful, dark-skinned Madonna merging her into their pantheon of Lwa, and meshing her with Erzulie Dantor. It should also be noted that at this time, it was considered most dangerous to worship images of African Lwa, whilst working on plantations those using Vodou iconographywere subjected to violent punishments. Slaves, in order to conceal their activities, often utilised Catholic saint iconography but instead of typical Catholic devotion their praxis involved syncretic actions deriving from their African ancestry.

Symbolism: Saint and Vodou Spirit

The symbolism of the Black Madonna is intriguing. Her crown signifies that Erzulie Dantor is the Queen of the dead, or ancestors. Ancestor worship is a common practice across Africa. In the Polish image of Our Lady of Czestochowa we see seven jewels in her crown. Likewise, Dantor’s characteristic number is seven, as she is known to have seven children and endured seven jabs of a knife. There is even a song memorializing this called the “Seven Stabs.”

In Vodou the Christ child is transformed into Erzulie Dantor’s lover and son, Ti-Jean, who has his own separate devotion among Vodouists. In some variants of Vodou the child she is holding is considered her daughter Anais, who is her interpreter. Erzulie Dantor has scratches on her cheek because of a fight with her sister, Erzulie Freida, over a lover. In other depictions the Christ child is holding a box, which represents a coffin in Vodou.

Love and Lesbians

Erzulie Dantor is the compassionate mother of the oppressed, children, victims of sexual assault, the loveless and the forgotten. But Erzulie is far more sensuous than the Virginal Marian advocation from which she was inspired. Considered a sensual ‘hot spirit’, Erzulie Dantor is invoked for love spells. She is often alluded to as a spirit of love, romance, art, jealously, passion and sex. Those possessed by her may lose the ability to speak, as she is considered mute, and may dance erotically.

Like St. Sebastian and Santa Muerte, she is a matroness of the LGBT community in Haiti and for many Haitian-Americans in cities such as Miami and New York. In particular, she is said to be the defender of lesbians, whilst her sister, Erzulie Freda, responsible according to some accounts for the scars on her sister’s cheek, is the matron of gay men, especially drag queens.

Vengeance and Vodou

Like Santa Muerte, Erzulie Dantor is a feisty character. Although she maternally protects women and children, she is also said to be a battle-axe with a wild streak who will ferociously defend them from danger. Vodou practitioners assert that aside from lesbians she also gives her spiritual aegis to businesswomen, unwed mothers, and battered women. As the expression goes ‘hell hath no fury like a woman’s wrath.’ Erzulie is known for being vengeful, vindictively using her Vodou powers to bring misfortunes to straying lovers, gay bashers and abusive husbands.

Supplicating Erzulie

Vodouisants who display statues of the Black Madonna adorn them with her colours, blue, green and red as well as her favourite drinks. Petitions to her must be made in a fire. She loves knives, silver, swords, and sharp objects on her altar as well as rum. Erzulie Dantor is believed to have possessed an actual Haitian female revolutionary (Mambo Marinette) who fought in the war for independence against France. Legend has it her tongue was cut out and she was tortured before she died. Mambo Marinette is symbolized by Anima Sola, the Catholic image of a female soul amidst the flames of purgatory. Erzulie Dantor is not limited to association with Our Lady of Czestochowa, but also is identified with the images of Mater Salvatoris, Our Lady of Mount Caramel, Our Lady of Lourdes, and Our Lady of Perpetual Help. In Haitian Vodou there are many “Erzulies.” However, in all her variations Erzulie Dantor is one the most beloved and revered maternal figures who fights for justice and protects her children.

Black is Beautiful

Our Lady of Czestochowa is one of many Black Madonnas hailing from medieval Europe. There is no consensus as to why these icons were created with dark skin. Arguments vary, some suggest that the images may have been created with dark skin to match that of the indigenous people or that they turned black over time due to smoke and aging. In Spain, which was under Muslim rule for seven centuries, one theory posits that some images of Catholic saints and the Virgin turned black while hidden underground from Islamic iconophobes. Due to her black skin, the Madonna’s appeal was tantalising to Vodouisants who banned from utilising their own iconography at risk of punishment, sought new ways to supplicate their spirits. The injured visage of Our Lady of Czestochowa also had a potent signification to the Haitian people who had been physically and psychologically scarred at the hands of the colonisers.

Syncretic Feminine Synergies

As the case of the Black Madonna who became Erzulie Dantor evinces, outside influences and even banning a religion, cannot always erode a faith. Instead exogenous elements may meld into it, causing it to metamorphose and make new models of being, belonging and battling with the difficulties of our world. In the Black Madonna, Vodou practitioners fashioned a new facet of the pre-existing figure of Erzulie Dantor, indubitably in alignment with the arduousness of their quotidian realities as Haitian women warred alongside men against the French, 200 years ago. From the grievances they generated a strong, powerful female spirit whose tenacity compelled her to fight for justice.

Women today continue to face brutality, marital difficulties, domestic violence, struggle to raise their children, support their family financially and battle to enjoy the freedom of their own sexual choices. If they still turn to the Black Madonna, Erzulie Dantor, it is as they need a spiritual figure who both reflects their strengths, understands their hardships and armours them with the spiritual tools to overcome the trials and tribulations of life on this precarious planet.

*Debra Van Neste is the Founder of “Thinking Agenda” an anti-cult organization.

She is the editor of “Ethics and the Modern Guru” a magazine on cults, culture and new religious movements. She was initiated as a Mambo in Haitian Vodou in 2006 and left the practice in 2012. †Dr. Kate Kingsbury obtained her doctorate in anthropology at the University of Oxford, where she also did her Mphil. Dr. Kingsbury is a polyglot fluent in English, French, Spanish. She is a polymath interested in exploring the intersections between anthropology, religious studies, philosophy, sociology and critical theory. Dr. Kingsbury is Adjunct Professor at the University of Alberta, Canada. She is fascinated by religious phenomena, not only in terms of their continuity across the Holocene and into the Anthropocene but equally interested in the changes wrought to praxis and belief by humans ensuring the infinite esemplasticity that is inherent to all religions, allowing for their inception, survival, alteration, regeneration and expansion across time and space. Dr. Kingsbury is a staunch believer in equal rights and the power of education to ameliorate global disparities. She also works pro bono for a non profit organisation, Uganda4Her, that aims to empower and educate girls in Uganda. Follow Dr. Kingsbury on Twitter.